The 1963 March on Washington's 60th Year Anniversary

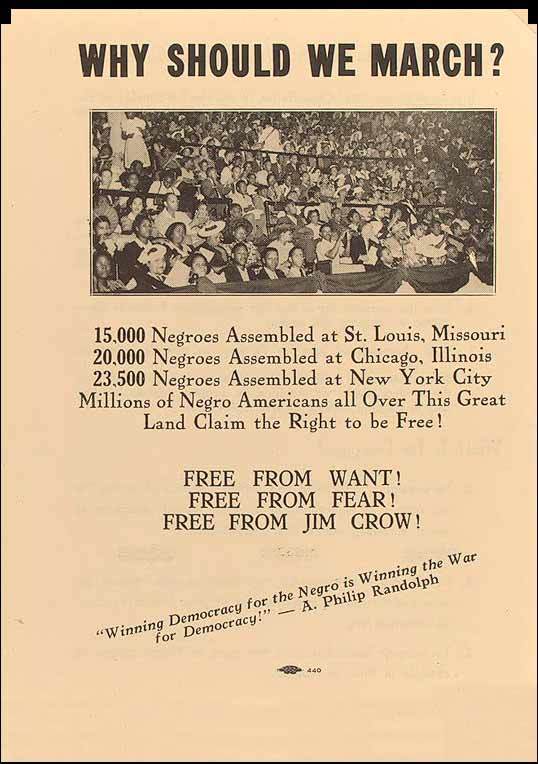

It has been sixty years since the historic 1963 March on Washington existed. It was a major event of the American Civil Rights Movement, of the black freedom struggle, and of the overall human rights movement in general. Over two hundred thousand human beings came into Washington, D.C. from buses, planes, trains, cars, and by other means to advocate for human justice. Speeches were made from John Lewis to Daisy Bates (a civil rights activist from Little Rock, Arkansas), hope was widespread in the atmosphere, and there was a contagious, stirring energy filled with inspiration. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his historic "I Have a Dream" speech to not only have hope for racial justice, but Dr. King condemned American racism as contributing to a society filled with nefarious, wicked injustices (like police brutality, racism, labor exploitation, and poverty). He compared the corrupt system to false promissory note marked insufficient funds. The dream of the march existed back during the 1940's. Back then, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin wanted the desegregation of the wartime industries being caused by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt or there will be a march on Washington. FDR conceded, because FDR didn't want more controversies to be made manifest during the midst of World War II. Yet, A. Philip Randolph always wanted an actual March on Washington to happen in confronting racial injustice and economic oppression. He had his wish by August of 1963. John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, and other human beings organized the historic 1963 march. It has its problems like the march restricted many women voices unfairly, Malcolm X classified the rally as a liberal establishment puppet show, and many speeches were whitewashed or sugarcoated to please the Kennedy administration's politically correct sensibilities. The strengths of the March on Washington were that it was very peaceful, it energized the crowds of people, and it was a major catalyst for the passage of civil rights and voting rights legislation in the United States of America. It took a team of men, women, and children of every color to establish the 1963 March on Washington to be a great success. Likewise, we have a long way to go to make the Dream real as we all know.

The Prelude

The 1963 March on Washington, D.C. took place historically in various stages. It was decades in the making. It took place on August 28, 1963, and the title of the march was "The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom." It was the dream of A. Philip Randolph, who was the President of the Negro American Labor Council and vice President of the AFL-CIO. Randolph was the President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (or a powerful labor union involving black Americans porters in trains across America. He wanted a civil rights march in 1941 (with about 100,000 black workers) with Bayard Rustin. It was planned for July 1, 1941. Yet, it didn't happen after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt wrote Executive Order 8802. This executive order forced equal opportunity in the defense industry, which meant that all workers had to be treated the same, no matter what their race was. It was the first major federal civil rights policy since the days of Reconstruction in America. Randolph allowed this to happened after telling FDR that he will make a march in Washington, D.C. if he didn't ban discrimination in the defense industry. African Americans were free from legalized slavery by the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Yet, black Americans were still not free from Jim Crow apartheid, rape, lynching, voting rights suppression, economic oppression, racism, sexism, and other evils (that were permitted by the government, private racists, and the structures of society in general). Many people forget that Jim Crow apartheid was legal which means that it was an unjust law. By the 19th and 20th centuries, many African Americans grew organizations and institutions that were dedicated to fight for social change.

After 1941, Randolph and Rustin organized to promote a March on Washington. Their Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, held at the Lincoln Memorial on May 17, 1957, featured key leaders including Adam Clayton Powell, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Roy Wilkins. Mahalia Jackson performed at the location. By 1963, the Civil Rights Movement has grown into a new level. Civil rights activists used demonstrations, boycotts, nonviolent direct action across the United States of America. 1963 was the 100th year anniversary of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln. This was a new time. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) put aside their differences and united to promote the march. Black people, white people, Latino people, Asian people, and people of every background came together to promote change the 1963 March in Washington. 1963 saw violent confrontations all over the South in places like: in Cambridge, Maryland; Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Goldsboro, North Carolina; Somerville, Tennessee; Saint Augustine, Florida; and across Mississippi. In most cases, white people attacked nonviolent demonstrators seeking civil rights. Many people wanted the March on Washington to have civil disobedience, some wanted just a protest, and others wanted a complete shutdown of the city. Many activists didn't want tokenism. Dr. King regularly criticized the Kennedy administration for not going far enough on civil rights before 1963. We know Malcolm X criticized the Kennedy administration. The truth is that the Kennedy administration was light years more progressive on civil rights than previous administrations, but it still had a lot of work to do on civil rights issues too.

Organizing and Building

On May 24, 1963, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy invited African-American novelist James Baldwin, along with a large group of cultural leaders, to a meeting in New York to discuss race relations. Lorraine Hansberry was at the meeting this. This event was one of the most unknown, unsung events of the Civil Rights Movement. James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, and other civil rights activists wanted Kennedy to have a true understanding of the depth of racism in society. The Kennedy administration wanted primarily the law and the court system to eliminate racism in society. James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, and other leaders instead wanted both the courts (and the law) along with active, direct social activism (even self-defense, not just non-violence) to eliminate racism in society. I agree with James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, and other civil rights leaders in that meeting. This disagreement caused a debate in the meeting. It showed the divide between Black America and the Washington political leaders. The murder of Medgar Evers changed everything along with the Birmingham rights Movement. The callous murder of Medgar Evers (in front of his home when Evers was a father and a man who risked his life for black freedom) inspired the Kennedy administration to take things into the next level. The Baldwin Kennedy meeting also pushed the Kennedy administration too. On June 11, 1963, President Kennedy gave a notable civil rights address on national television and radio, announcing that he would begin to push for civil rights legislation. That night (early morning of June 12, 1963), Mississippi activist Medgar Evers was murdered in his own driveway, further escalating national tension around the issue of racial inequality. After Kennedy's assassination, his proposal was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The official planning and organization of the 1963 March on Washington started by December 1961 by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. They wanted 2 days of protests and sit ins plus lobbying. They wanted a mass rally at the Lincoln Memorial. Both men wanted to focus on joblessness and to have a public works program to employ black people. As early as the early 1960's, economists predicted an increase of automation and deindustrialization (with the rise of the economies of West Germany and Japan), so a radical economic policy was necessary to build up the economic futures of black Americans. They received help from Stanley Aronowitz of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers; he gathered support from radical organizers who could be trusted not to report their plans to the Kennedy administration. The unionists offered tentative support for a march that would be focused on jobs. By May 15, 1963, Randolph said that he wanted an October Emancipation March on Washington for Jobs. The NAACP and the Urban League didn't support the march yet. Randolph won support from union leaders like the UAW's liberal Walter Reuther, but not of AFL–CIO president George Meany (who was more conservative). Randolph and Rustin intended to focus the March on economic inequality, stating in their original plan that "integration in the fields of education, housing, transportation and public accommodations will be of limited extent and duration so long as fundamental economic inequality along racial lines persists." As they negotiated with other leaders, they expanded their stated objectives to "Jobs and Freedom", to acknowledge the agenda of groups that focused more on civil rights.

By June of 1963, leaders from many organizations joined forces to establish the Council for Untied Civil Rights Leadership. This group coordinated funds and the message. Its leaders were called the Big Six. It included Randolph, chosen as titular head of the march; James Farmer, president of the Congress of Racial Equality; John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; Roy Wilkins, president of the NAACP; and Whitney Young, president of the National Urban League. King in particular had become well known for his role in the Birmingham campaign and for his Letter from Birmingham Jail. Wilkins and Young initially objected to Rustin as a leader for the march, worried that he would attract the wrong attention because he was a homosexual, a former Communist, and a draft resister. The irony is that Rustin would late be adamantly anti-Communist later in his life, and Rustin even said that Dr. King went too far in his opposition to the unjust Vietnam War. They eventually accepted Bayard Rustin as deputy organizer, on the condition that Randolph act as lead organizer and manage any political fallout. About two months before the march, the Big Six broadened their organizing coalition by bringing on board four white men who supported their efforts: Walter Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers; Eugene Carson Blake, former president of the National Council of Churches; Mathew Ahmann, executive director of the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice; and Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress. Together, the Big Six plus four became known as the "Big Ten." John Lewis later recalled, "Somehow, some way, we worked well together. The six of us, plus the four. We became like brothers."

President Kennedy feared at first that such a march would provoke violence and chaos on June 22, 1963. The civil rights leaders wanted the march. Wilkins wanted people to rule out civil disobedience as a compromise. Dr. King and Whitney Young agreed with this policy. Leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), who wanted to conduct direct actions against the Department of Justice, endorsed the protest before they were informed that civil disobedience would not be allowed. Finalized plans for the March were announced in a press conference on July 2. It is no secret that SNCC and the SCLC disagreed on the tactics of finding justice but not on the overall goal. Bayard Rustin was an expert organizer, so he mobilized and used logistics to make the march a success. Rustin was a civil rights veteran and organizer of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, the first of the Freedom Rides to test the Supreme Court ruling that banned racial discrimination in interstate travel. Rustin was a long-time associate of both Randolph and Dr. King. With Randolph concentrating on building the march's political coalition, Rustin built and led the team of two hundred activists and organizers who publicized the march and recruited the marchers, coordinated the buses and trains, provided the marshals, and set up and administered all of the logistic details of a mass march in the nation's capital. During the days leading up to the march, these 200 volunteers used the ballroom of Washington DC radio station WUST as their operations headquarters. Even some civil rights activists were worried about violence with the march. Malcolm X condemned the march as the "farce on Washington." Malcolm X (then a member of the Nation of Islam) felt that the march was a liberal establishment puppet show used to water down the progress of black revolutionary change. Some organizers disagreed about the purpose or reason of the march.

The NAACP and Urban League saw it as a gesture of support for the civil rights bill that had been introduced by the Kennedy Administration. Randolph, King, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) believed it could raise both civil rights and economic issues to national attention beyond the Kennedy bill. CORE and SNCC believed the march could challenge and condemn the Kennedy administration's inaction and lack of support for civil rights for African Americans. The organizations did ultimate unite for civil rights legislation, ending school segregation, have a public works programs, a federal law banning public and private discrimination, a higher minimum wage, enforce the 14th Amendment, expand the Fair Labor Standards Act, and allow the Attorney General to have injunctive suits when constitutional rights of citizens were violated. Although in years past, Randolph had supported "black only" marches, partly to reduce the impression that the civil rights movement was dominated by white communists, organizers in 1963 agreed that white and black people marching side by side would create a more powerful image. The Kennedy administration worked with the organizers in planning the March. Chicago and New York City (as well as some corporations) agreed to designate August 28 as "Freedom Day" and give workers the day off. Some far right people including Hoover claimed that the March was Communist inspired (which is a lie). Even FBI agent William C. Sullivan had a large report on August 23 saying that Communists failed to infiltrate the civil rights movement. Far right hypocrite Strom Thurmond (who committed adultery, supported segregation, and had a biracial child) attacked the March as Communist.

Organizers worked hard at a building at West 130th St. and Lenox in Harlem, NYC. Activists sold buttons to promote the march. The button featured two hands shakings with the words of "March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom", a union bug, and the date August 28, 1963. By August 2, they had distributed 42,000 of the buttons. Their goal was a crowd of at least 100,000 people. As the march was being planned, activists across the country received bomb threats at their homes and in their offices. The Los Angeles Times received a message saying its headquarters would be bombed unless it printed a message calling the president a "N_____ Lover." Five airplanes were grounded on the morning of August 28 due to bomb threats. A man in Kansas City telephoned the FBI to say he would put a hole between King's eyes; the FBI did not respond. Roy Wilkins was threatened with assassination if he did not leave the country. Previously, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had a march in Detroit (called the Walk for Freedom on June 23, 1963) where he gave a similar Dream speech about racial justice and economic justice.

By August 28, 1963, thousands of human beings came to Washington, D.C. on Wednesday. They traveled by road, rail, and air. Marchers from Boston traveled overnight and arrived in Washington at 7am after an eight-hour trip, but others took much longer bus rides from cities such as Milwaukee, Little Rock, and St. Louis. Organizers persuaded New York's MTA to run extra subway trains after midnight on August 28, and the New York City bus terminal was busy throughout the night with peak crowds. A total of 450 buses left New York City from Harlem. Maryland police reported that "by 8:00 a.m., 100 buses an hour were streaming through the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel." The United Automobile Workers financed bus transportation for 5,000 of its rank-and-file members, providing the largest single contingent from any organization. One reporter, Fred Powledge, accompanied African Americans who boarded six buses in Birmingham, Alabama, for the 750-mile trip to Washington. The people in the march prayed that violence wouldn't exist. It was unprecedented during that time. Some participants who arrived early held an all-night vigil outside the Department of Justice, claiming it had unfairly targeted civil rights activists and that it had been too lenient on white supremacists who attacked them. Some people waited long hours. The federal government used D.C. police, 2,000 men from the National Guard, and other soldiers to protect the marchers. The Pentagon had 19,000 troops in the suburbs. This Operation Steep Hill plan was enacted. Liquor sales were banned in Washington, D.C. Hospitals stockpiled blood plasma and cancelled elective surgeries. Many games were cancelled. The sound system was formed. On August 28, more than 2,000 buses, 21 chartered trains, 10 chartered airliners, and uncounted cars converged on Washington.

Marchers were not supposed to create their own signs, though this rule was not completely enforced by marshals. Most of the demonstrators did carry pre-made signs, available in piles at the Washington Monument. The UAW provided thousands of signs that, among other things, read: "There Is No Halfway House on the Road to Freedom," "Equal Rights and Jobs NOW," "UAW Supports Freedom March," "in Freedom we are Born, in Freedom we must Live," and "Before we'll be a Slave, we'll be Buried in our Grave.

About 50 members of the American Nazi Party staged a counter-protest and were quickly dispersed by police. The rest of Washington was quiet during the March. Most non-participating workers stayed home. Jailers allowed inmates to watch the March on TV. Representatives from sponsoring organizations addressed the crowd from the podium at the Lincoln Memorial. Those speakers were from the Big Ten (that included the Big Six too), religious leaders (Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish leaders), and labor leader Walter Reuther.

The Beginning of the March

The events of the 1963 March on Washington, D.C. were diverse. Representatives from the Big Ten groups addressed the crowd. The big mistake in the march was that none of the official speeches was made by a woman. Dancer, activist, and actress Josephine Baker gave a speech during the preliminary offerings, but women were limited in the official program to a "tribute" led by Bayard Rustin, at which Daisy Bates also spoke briefly. Sexism in the civil rights movement is wrong and evil. Floyd McKissick read James Farmer's speech because Farmer had been arrested during a protest in Louisiana; Farmer wrote that the protests would not stop "until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the North." There were more than 10 major speakers in the rally who were including A Philip Randolph (the March director), Walter Reuther (UAW leader and leader of AFL-CIO), Roy Wilkins (from the NAACP), John Lewis (Chair of SNCC), Daisy Bates (a leader from Little Rock, Arkansas), Dr. Eugene Carson Blake (part of the United Presbyterian Church and the National Council of Church), CORE's Floyd McKissick, National Urban League leader Whitney Young, Rabbi Joachim Prinz (of the American Jewish Congress), Mathew Ahmann (of the National Catholic Conference), Josephine Baker, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The closing remarks were made by A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, who were march organizers. The march led with the Pledge and a list of progressive demands.

Iconic singer Marian Anderson was scheduled to lead the National Anthem. She was unable to arrive on time. So, Camilla Williams performed in her place. The invocation was made by Washington's Roman Catholic Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle. Opening remarks were given by march director A. Philip Randolph, followed by Eugene Carson Blake. There was an ironic celebration of black women fighters for freedom, but black women weren't allowed to speak massively in the march (which was wrong and a product of sexism). Daisy Bates spoke briefly in place of Myrlie Evers, who had missed her flight. The tribute introduced Daisy Bates, Diane Nash, Prince E. Lee, Rosa Parks, and Gloria Richardson.

Following that, speakers were SNCC chairman John Lewis, labor leader Walter Reuther, and CORE chairman Floyd McKissick (substituting for arrested CORE director James Farmer). The Eva Jessye Choir sang, and Rabbi Uri Miller (president of the Synagogue Council of America) offered a prayer. He was followed by National Urban League director Whitney Young, NCCIJ director Mathew Ahmann, and NAACP leader Roy Wilkins. After a performance by singer Mahalia Jackson, American Jewish Congress president Joachim Prinz spoke, followed by SCLC president Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Rustin read the March's official demands for the crowd's approval, and Randolph led the crowd in a pledge to continue working for the March's goals. The program was closed with a benediction by Morehouse College president Benjamin Mays.

Although one of the officially stated purposes of the march was to support the civil rights bill introduced by the Kennedy Administration, several of the speakers criticized the proposed law as insufficient. Two government agents stood by in a position to cut power to the microphone if necessary. Roy Wilkins announced that legendary sociologist and activist W.E.B. DuBois had died in Ghana the previous night. DuBois was in exile, and the crowd observed a moment of silence in his memory. Wilkins (who was a more moderate civil rights leader. He called Black Power racist which isn't true. Also, he disagreed with Dr. King's opposition to the Vietnam War. Wilkins only opposed the Vietnam War when Nixon was President) and didn't want to announce the news, because he didn't agree with DuBois becoming a Communist. He did because Randolph would have done it. Wilkins said: "Regardless of the fact that in his later years, Dr. Du Bois chose another path, it is incontrovertible that at the dawn of the twentieth century, his was the voice that was calling you to gather here today in this cause. If you want to read something that applies to 1963 go back and get a volume of The Souls of Black Folk by Du Bois, published in 1903."

Controversies

John Lewis of SNCC was the youngest speaker at the event. He wanted to give a stronger speech to criticize the Kennedy administration for the inadequacies of the Civil Rights Act of 1963 and not going far enough to fight for racial justice. James Forman and other SNCC leaders contributed to the revision. They felt that Kennedy didn't do enough to protect southern black human beings and civil rights workers from physical violence by white racists in the Deep South. Many leaders in the march wanted his original speech to be changed. John Lewis at first refused, but he did it out of respect for Randolph (who spent his whole life making the march a reality). The following words of John Lewis's speech are parts that were deleted:

"...In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the administration's civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late. ...I want to know, which side is the federal government on? ...The revolution is a serious one. Mr. Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the streets and put it into the courts. Listen, Mr. Kennedy. Listen, Mr. Congressman. Listen, fellow citizens. The black masses are on the march for jobs and freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won't be a "cooling-off" period... We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently ..."

John Lewis's original speech was sent to organizers and the media. Reuther, O'Boyle, and others falsely thought it was too divisive and militant, but these men didn't experience what black people have experienced for centuries in America. O'Boyle from the Catholic delegation was about to leave the march at one point before the Lewis original speech. Rustin informed Lewis at 2 A.M. on the day of the march that his speech was unacceptable to key coalition members (Rustin also reportedly contacted Tom Kahn, mistakenly believing that Kahn had edited the speech and inserted the line about Sherman's March to the Sea. Rustin asked, "How could you do this? Do you know what Sherman did?" Rustin needed to know back then that the Confederate terrorists weren't playing checkers. They were traitors). Yet, Lewis did not want to change the speech. Other members of SNCC, including Kwame Ture, were also adamant that the speech is not censored. The dispute continued until minutes before the speeches were scheduled to begin. Under threat of public denouncement by the religious leaders, and under pressure from the rest of his coalition, Lewis agreed to omit some of the passages. Many activists from SNCC, CORE, and SCLC were angry at what they considered censorship of Lewis's speech. In the end, Lewis added a qualified endorsement of Kennedy's civil rights legislation, saying: "It is true that we support the administration's Civil Rights Bill. We support it with great reservation, however." Even after toning down his speech, Lewis called for activists to "get in and stay in the streets of every city, every village and hamlet of this nation until true freedom comes."

James Baldwin was prevented to give his speech, because everybody knows that James Baldwin was too militant and progressive. Baldwin said that the March was co-opted by interests from the establishment. Despite the protests of organizer Anna Arnold Hedgeman, no women gave a speech at the March. Male organizers attributed this omission to the "difficulty of finding a single woman to speak without causing serious problems vis-à-vis other women and women's groups." We know that to be a total lie as tons of women were leaders and activists in the movement. Although Gloria Richardson was on the program and had been asked to give a two-minute speech, when she arrived at the stage her chair with her name on it had been removed, and the event marshal took her microphone away after she said "hello." Richardson, along with Rosa Parks and Lena Horne, was escorted away from the podium before Martin Luther King Jr. spoke. Early plans for the march would have included an "Unemployed Worker" as one of the speakers. This position was eliminated, furthering criticism of the March's middle-class bias. Singers like Mahalia Jackson, Joan Baez, Boy Dylan, Peter, Paul, and Mary, and Odetta performed. Some participants like Dick Gregory wanted more groups to participate in the singing and more black people to be singing. Walter Reuther wanted politicians to address injustices.

Dr. King's I Have a Dream Speech

Dr. Martin Luther Jr. gave his "I Have a Dream" speech during the march. He gave his dream previously in Detroit months before during the Walk for Freedom movement. The I Have a Dream was both a condemnation of injustices in America and a call for a better future. Dr. Martin Luther King was an American civil rights leader and a Baptist minister. In front of over 250,000 human beings, he gave his speech from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was one of the greatest speeches in human history. In the speech, Dr. King invoked the Emancipation Proclamation, the United States Constitution, and religious themes to make the point that racism and oppression have no place in our world. There are two major parts of the I Have a Dream speech. The first part was the condemnation of American racism, poverty, of injustice in general, and the structural forms of evil harming black Americans. Dr. King wanted to use real language to make a distinction between the American reality (filled with police brutality and economic oppression) and the American dream. Dr. King said that "our federal government has also scarred the dream through its apathy and hypocrisy, its betrayal of the cause of justice." King suggested that "It may well be that the Negro is God's instrument to save the soul of America." Dr. King gave a similar I Have a Dream speech on November 27, 1962, King gave a speech at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. The 1963 March on Washington I Have a Dream speech was drafted with the assistance of Stanley Levison and Clarence Benjamin Jones in Riverdale, New York City. Jones has said that "the logistical preparations for the march were so burdensome that the speech was not a priority for us" and that, "on the evening of Tuesday, Aug. 27, [12 hours before the march] Martin still didn't know what he was going to say." Dr. King, a student of American history, invoked the Abraham Lincoln Gettysburg Address too. He wanted to have urgency in his words by saying "Now is the time."

Among the most quoted lines of the speech are "I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!" According to US Representative John Lewis, who also spoke that day as the president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, "Dr. King had the power, the ability, and the capacity to transform those steps on the Lincoln Memorial into a monumental area that will forever be recognized. By speaking the way he did, he educated, he inspired, he informed not just the people there, but people throughout America and unborn generations." King describes the promises made by America as a "promissory note" on which America has defaulted. He says that "America has given the Negro people a bad check", but that "we've come to cash this check" by marching in Washington, D.C. The style of old-school black Christian speeches were found in the cadence of his words. Biblical phrases were found in his words too.

Toward the end of the speech, King departed from his prepared text for a partly improvised peroration on the theme "I have a dream", prompted by Mahalia Jackson's cry: "Tell them about the dream, Martin!" In this part of the speech, which most excited the listeners and has now become it is most famous, King described his dreams of freedom and equality arising from a land of slavery and hatred. In the final parts of the speech, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said these words:

"...I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that, let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, Black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last. Free at last. Thank God almighty, we are free at last..."

Immediately, the crowd in Washington, D.C. experienced a sense of euphoria, joy, and happiness over the speech. Hoover hated Dr. King because of jealousy. COINTELPRO head and FBI agent William C. Sullivan considered Dr. King the "most dangerous" black man in the future of the nation after his I Have a Dream speech. At the end of the speech, the crowd soared in joy and inspiration to find solutions. In the wake of the speech and march, King was named Man of the Year by TIME magazine for 1963, and in 1964 he was the youngest man ever awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The 1963 March on Washington event featured many prominent celebrities in addition to singers on the program. Josephine Baker, Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, James Baldwin, Jackie Robinson, Sammy Davis, Jr., Dick Gregory, Eartha Kitt, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Diahann Carroll, and Lena Horne were among the black celebrities attending. There were also quite a few white and Latino celebrities who attended or helped fund the March in support of the cause: Tony Curtis, James Garner, Robert Ryan, Charlton Heston, Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Rita Moreno, Marlon Brando, Bobby Darin, and Burt Lancaster, among others. Judy Garland was part of the planning committee and was also scheduled to perform but had to drop out at the last minute due to commitments to her TV variety series.

Temporary Euphoria

The 1963 March on Washington ended with a great sense of enthusiasm. President John F. Kennedy watched the march on television and was pleased. The march wasn't perfect as it excluded many women speakers, some speeches were watered down, and there was co-option by some establishment interests (as said by Malcolm X and other critics. Malcolm X's Message to the Grass Roots speech criticized the march as a picnic and a circus), but the crowd of the people was inspired to fight for social change. The chances for the civil rights bill increased. Kennedy met with the march leaders in the White House on August 28, 1963. The news media covered the march massively. Randolph and Rustin abandoned their belief in the effectiveness of marching on Washington. King maintained faith that action in Washington could work but determined that future marchers would need to call greater attention to economic injustice.

The Aftermath

In 1967–1968, he organized a Poor People's Campaign to occupy the National Mall with a shantytown. Segregationists including William Jennings Bryan Dorn criticized the government for cooperating with civil rights activists. Senator Olin D. Johnston rejected an invitation to attend the march, because he was a white segregationist. The march was not perfect, but it inspired grassroots activism that caused the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to exist. Anniversary marches existed in 1983, 1988, and in 2013. Today, we have a long way to go. Kathleen Cleaver said that only revolution would cause American society to have the real redistribution of wealth and power to end exclusion and inequalities. There was the 2020 Virtual March on Washington, D.C. because of the COVID-19 pandemic. It opposed racial injustice and police brutality. On August 28, 2021, people marched for voting rights and for the statehood of Washington, D.C. Among the speakers were Martin Luther King III, his wife and Drum Major Institute president Arndrea Waters King, daughter Yolanda, National Action Network leader Rev. Al Sharpton and Washington D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser. Other speakers at the event included Democratic U.S. Representatives Joyce Beatty, of Ohio, Terri Sewell, of Alabama, Sheila Jackson Lee and Al Green, both of Texas, and Mondaire Jones, of New York; NAACP president Derrick Johnson; and Philonise Floyd, activist and brother of George Floyd.

The Legacy of the 1963 March on Washington

August 1963 March on Washington was a historic display of organizing, effort, controversies, and a sense of rededication for the fight for human liberation. Many speakers came, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. motivated and inspired the crowd with his "I Have a Dream": speech. Since 1963, we have seen the growth of social activism, but racial injustice and economic inequality haven't been gone. The paradox of this time in 2023 is that the sacrifices of the civil rights movement decades ago are being opposed by not only the far-right alt right movement (which is complicit in the terrorist murders at Charleston, South Carolina against black people in 2015, the U.S. Capitol insurrection on January 6, 2021, etc.) but by neoliberal moderates who endorse Western imperialism, assassinations by drones, police state measures domestically, and military aggression overseas. We see homeownership being a struggle for many in our communities, and we witness corporate exploitation. It is no secret that the capitalist elites and their political agents wanted to contain and co-opt the revolutionaries of the civil rights movement to promote compromising policies. The black freedom struggle involved civil disobedience, self-defense, the Freedom Rides, the voter registration drive, and the fight or jobs and being opposed to poverty. Later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. went beyond trying to end Jim Crow segregation. He saw that eliminating inequality requires to look at political, social, and class issues that caused him to be a strong opponent of the War in Vietnam (that caused Dr. King to be in conflict with members of the NAACP and the administration of Lyndon Johnson).

Dr. King was right to say that, "When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, militarism, and economic exploitation are incapable of being conquered." When Dr. King questioned capitalism and imperialism, the federal government considered him a threat (the NSA, the FBI, and military Intelligence illegally monitored Dr. King and his allies), and he was unjustly assassinated at Memphis on April 4, 1968. By 2013, the Economic Policy Institute created many reports about the topic of "The Unfinished March." These reports studied the goals of the original march and tried to find out how much progress was made. They promoted the views of Randolph and Rustin that civil rights alone can't transform the people's quality of life without economic justice. I agree with them on that issue. The reports said that the March's main goals (of housing, integrated education, and widespread employment at living wages) wasn't accomplished. They mentioned that legal advances were made. Yet, black people in many cases live in concentrated areas of poverty where many black people have miseducation and unemployment. Dedrick Muhammad of the NAACP wrote that racial inequality of income and homeownership has increased since 1963 and worsened during the recent Great Recession. There is a distinction of the masses of black people and other human beings fighting for social change and the moderate corporate heads who desire the status quo (the status quo system allows a few of the African American population to be millionaires and billionaires while the capitalist system remains intact to oppress everyone else). This must change. The 1963 March on Washington was a start of the turning point in American history of the necessity to speak out and do action in creating a just world for us and our descendants (in the realms of independence, justice, collective power, and freedom).

By Timothy

No comments:

Post a Comment