St. Louis

The Midwestern city of St. Louis has a long history and

vibrant culture. It is a major port in the state of Missouri and it's fond on the western

bank of the Mississippi River. It is a city that borders Illinois. It has over

310,000 people and its metropolitan area has almost 3 million people. St. Louis

has a diverse history too. Like other Midwestern cities, it has a culture that

is diverse filled with immigrants, black people, great art, excellent cuisine,

and lively institutions. Like other cities, it was once a depot of segregation

and other injustices that courageous people in St. Louis fought to end. It is a

city with gorgeous architecture and down to Earth human beings. From 1764 (when

it was founded by the French fur traders Pierre Laclède and Auguste Chouteau.

The city was named after the King Louis IX of France) to the present, St. Louis

is filled with a history of development and growth. St. Louis has the Forest

Park Jewel Box, MetroLink, the St. Louis Art Museum, the Gateway Arch, etc. The

economy of St. Louis deals with service, manufacturing, trade, transportation

of goods, and tourism. Many corporations are in the metro area of St. Louis

like Anheuser-Busch, Express Scripts, Boeing Defense, Scottrade, Go Jet, etc.

It has a large medical, pharmaceutical, and research presence too. Its current

mayor is Lyda Krewson. It is a city of 66 square miles. To the East of St.

Louis is found East St. Louis, Illinois. South of St. Louis include Cahokia and

Columbia (which are both found in Illinois). North of St. Louis are Castle

Point and Jennings (both found in Missouri). Ferguson and Florissant are found

northwest of St. Louis. Clayton, Chesterfield, and Richmond Heights are found

to the West of St. Louis. It's a home to architects, musicians, social

activists, teachers, other scholars, scientists, engineers, doctors, nurses,

athletes, lawyers, judges, politicians, and other contributors to society. St.

Louis is here to stay and we will always respect the great culture and the

great people of St. Louis, Missouri.

Early St. Louis

St. Louis has a long history. In the beginning, the first

people of St. Louis were Native Americans. Native Americans built the complex,

highly advanced Mound builder civilization.

The people of the Mississippian culture created more than two dozen

burial mounds around the area of the city of St. Louis. These mounds existed in

ca. 1050 A.D. Some settlements of early St. Louis are preserved at the Cahokia

Mounds site in Illinois. The mounds in St. Louis were almost all demolished.

Only one mound remains within the city called Sugarloaf Mound. Although, St.

Louis maintained the nickname of “The Mound City” well into the 19th century.

Many Native Americans settled along the Mississippi River and its tributaries,

especially the Missouri River. Many Native Americans created canoes for

transportation out of the large forests in the region. The end of the

Mississippian culture by the 14th century resulted in a new era of history in

the area. There were French Canadian settlers and Siouan speaking groups like

the Missouri and the Osage migrating into the Missouri valley. They lived in

villages along the Osage and Missouri rivers. Both groups had conflict with the

northeastern tribes like the Sauk and the Fox. All four of these groups

confronted the earliest explorers of Missouri. Europeans explored the area

almost a century before the city of St. Louis was officially founded. By the

early 1670’s, Jean Talon, went along the Mississippi River after hearing of

rumors that it connected to the Pacific Ocean. So, explorer Louis Joliet and

Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette came into the Mississippi River on June 1673.

They traveled past the confluence of the Missouri and Mississippi to the mouth

of the Arkansas River. At this point Joliet returned north after determining the

river would not reach the Pacific and fearing attack by Spanish settlers. Nine

years later, the French explorer La Salle led an expedition south from the

Illinois River to the mouth of the Mississippi. He claimed the entire valley

for France.

La Salle named the Mississippi river basin Louisiana after

King Louis XIV. That region was between and near the confluence of the Ohio and

Mississippi was named Illinois Country. Many forts existed in the Mississippi

valley. In 1699, the French built a settlement on the east bank of the

Mississippi at Cahokia, Illinois, near the Cahokia Mounds complex. During the

next year, the Kaskaskia tribe formed a village at a small river. It was within

the present day area of St. Louis. There were two Jesuit priests, Pierre-Gabriel

Marest and Francois Pinet, who built a small mission at the site, naming the

river the River Des Peres (River of the Fathers). However, by 1703 the site was

abandoned as the Kaskaskia moved to the east bank and further south to a new

settlement named Kaskaskia, Illinois. A powerful monopoly involving trade was

sent to Antoine Crozat in the Mississippi Valley. He wanted to find and mine

precious stones, gold, and silver. Yet, Crozat’s venture failed by 1717,

because of Spanish interference. He relinquished his charter. The next company

to be granted a trade monopoly for the region was led by John Law. Law was a

Scottish financier. In 1717, Law convinced Louis XIV to provide the Company of

the West a 25-year monopoly of trade and ownership of all mines, while

promising to settle 6,000 whites and 3,000 black slaves (as a way to build

churches throughout the region). The company founded New Orleans as the capital

of Louisiana in 1718, and merged with other companies in 1719 to form the

Company of the Indies. There was a financial crisis. Law was ousted in 1720.

The Company of the Indies formed its capital of the Illinois Country (in upper

Louisiana) at Fort de Chartres. That location was 15 miles north of Kaskaskia

on the east bank of the Mississippi.

There was another early settlement. It was near present day

St. Louis. It was called Ste. Genevieve, Missouri. It was built in 1732 across

from the Kaskaskia village as a convenient port for salt and ore was mined on

the western side of the Mississippi. The Company of the Indies began making

trade ties with the Missouri River tribes during the early 1720’s and the

1730’s. French economic policy dealt with trade with the Spanish colony of New

Mexico to the southwest. Many trade expeditions between New Mexico and the

Mississippi valley occurred between 1739 and the Seven Years’ War of 1756-1763.

The war destroyed the wealth of many French trading firms and merchants based

in New Orleans. The French governor of Louisiana began granting trade

monopolies in several areas at the conclusion of the war to stimulate growth.

The founding of St. Louis

The St. Louis founding existed during the 18th century.

Jean-Jacques Blaise d’Abbadie was the new governor of Louisiana in June of

1763. He changed colonial policies. He moved to grant trade monopolies in the

middle Mississippi Valley to stimulate the economy. Among the new monopolists

was Pierre Laclede, who along with his stepson Auguste Chouteau set out in

August 1763 to build a fur trading post new the confluence of the Missouri and

Mississippi rivers. The settlement of St. Louis was established at a site south

of the confluence of the west bank of the Mississippi on February 15, 1764, by

Chouteau and a group of about 30 men. Laclede arrived at the side by mid-1764 and

provided detailed plans for the village, including a street grid and market

area. French settlers started to arrive form settlements on the east bank of

the Mississippi River in 1764. They were afraid of British control. This was

after the transfer of eastern land to Great Britain after the Treaty of Paris.

The local French lieutenant governor moved into St. Louis in 1765. He started

to award land grants to people.

There were peace negotiations to end the Seven Years’ War. It caused Spain to gain control of Louisiana according to the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. Due to travel times and the Louisiana Rebellion of 1768, the Spanish took official control in St. Louis only in May 1770. After the transfer, the Spanish confirmed French land grants and the Spanish provided local security. Most settlers in St. Louis were involved in farming. By the 1790’s, almost 6,000 acres were cultivated around St. Louis. Far trading was the major commercial focus of many residents. It was much more lucrative than agriculture during that period. The residents were not religious per se, but most of them were Roman Catholic. Most French people in America during that time were Roman Catholic. The first Catholic Church in St. Louis was built in mid-1770 and St. Louis had a resident priest by 1776. It caused Catholic religious observance a more customary component of life. The French settlers had both black and Native American slaves in St. Louis. Most of them worked as domestic servants. Some were agricultural laborers.

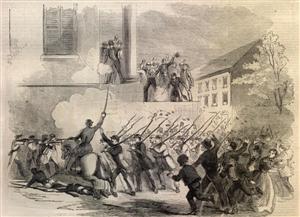

By 1769, the Spanish prohibited Native American slavery in Louisiana. Yet, it was still done among the French Creoles in St. Louis. Spanish governors ended the Native American slave trade. Yet, they allowed the retention of current slaves and any children born to them, which was evil. In 1772, a census determined the population of the village to be 637, including 444 whites (285 males and 159 females) and 193 African slaves, with no Indian slaves reported due to their technical illegality. During the 1770's and 1780's, St. Louis grew slowly and the Spanish commanders were replaced often. During the beginning of the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish governor Bernardo de Galvez (in New Orleans) helped the American rebels with weapons, food, blankets, tents, and ammunition. The Spanish lieutenant governors at St. Louis aided the colonists too. They especially helped the forces of George Rogers Clark during the Illinois campaign. On June 1779, the Spanish Empire came into the American Revolutionary War on the side of the Americans and the French. The British prepared to invade St. Louis and other Mississippi outposts. Yet, St. Louis was warned of the plans and residents fortified the town. On May 26, 1780, British and Indian forces attacked the town of St. Louis, but were forced to retreat due to the fortifications and defections of some Indian forces.

There were peace negotiations to end the Seven Years’ War. It caused Spain to gain control of Louisiana according to the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. Due to travel times and the Louisiana Rebellion of 1768, the Spanish took official control in St. Louis only in May 1770. After the transfer, the Spanish confirmed French land grants and the Spanish provided local security. Most settlers in St. Louis were involved in farming. By the 1790’s, almost 6,000 acres were cultivated around St. Louis. Far trading was the major commercial focus of many residents. It was much more lucrative than agriculture during that period. The residents were not religious per se, but most of them were Roman Catholic. Most French people in America during that time were Roman Catholic. The first Catholic Church in St. Louis was built in mid-1770 and St. Louis had a resident priest by 1776. It caused Catholic religious observance a more customary component of life. The French settlers had both black and Native American slaves in St. Louis. Most of them worked as domestic servants. Some were agricultural laborers.

By 1769, the Spanish prohibited Native American slavery in Louisiana. Yet, it was still done among the French Creoles in St. Louis. Spanish governors ended the Native American slave trade. Yet, they allowed the retention of current slaves and any children born to them, which was evil. In 1772, a census determined the population of the village to be 637, including 444 whites (285 males and 159 females) and 193 African slaves, with no Indian slaves reported due to their technical illegality. During the 1770's and 1780's, St. Louis grew slowly and the Spanish commanders were replaced often. During the beginning of the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish governor Bernardo de Galvez (in New Orleans) helped the American rebels with weapons, food, blankets, tents, and ammunition. The Spanish lieutenant governors at St. Louis aided the colonists too. They especially helped the forces of George Rogers Clark during the Illinois campaign. On June 1779, the Spanish Empire came into the American Revolutionary War on the side of the Americans and the French. The British prepared to invade St. Louis and other Mississippi outposts. Yet, St. Louis was warned of the plans and residents fortified the town. On May 26, 1780, British and Indian forces attacked the town of St. Louis, but were forced to retreat due to the fortifications and defections of some Indian forces.

In spite of their defeat, the British and their allies

destroyed much of St. Louis' agricultural lands and cattle stock, killed 23

residents, wounded 7, and captured between 25 and 75 as prisoners (some might

have been murdered after their capture). A subsequent counterattack launched

from St. Louis against British forts in the Midwest ended the threat of another

attack on the town. After the British were defeated, more French Creole

families evaded Anglo-American rule by moving to the Spanish-controlled land on

the west bank, including wealthy merchants Charles Gratiot, Sr. and Gabriel

Cerre. Both the Gratiot and Cerre families intermarried with the Chouteau family

to create a Creole-dominated society in the 1780's and 1790's. The families

also had marital ties to Spanish government officials, including the lieutenant

governors Piernas and Cruzat. During the 1790’s, towns near St. Louis grew.

This was when small farmers sold their lands to the Cerres, Gratiots, Soulards,

and the Chouteaus. These farmers moved into towns like Carondelet, St. Charles,

and Florissant. Only 43% of the district’s population lived within the village

by 1800 (1,039 of 2,447). The Spanish government secretly returned the

unprofitable Louisiana territory to France in October of 1800 in the Treaty of

San Ildefonso. The Spanish officially transferred control in October 1802. Yet,

the Spanish administrators were in charge of St. Louis throughout the time of

French ownership. Later, a team of American negotiators purchased Louisiana,

including St. Louis. On March 8 or 9, 1804, the flag of Spain was lowered at

the government buildings in St. Louis and, according to local tradition; the

flag of France was raised. On March 10, 1804, the French flag was replaced by

that of the United States.

This picture shows an evil slave auction in a St. Louis courthouse. Black people, many German immigrants, and others were strongly anti-slavery in St. Louis.

The Antebellum period

By the antebellum period, St. Louis experienced many

changes. The governor of the Indiana Territory by the beginning of the 1800’s

governed Louisiana District (which included St. Louis). The district’s

organizational law forbade the slave trade and reduced the influence of St.

Louis in the region. Wealthy St. Louisans petitioned Congress to review the

system. By July of 1805, Congress reorganized the Louisiana District as the

Louisiana territory with its territorial capital at St. Louis and its own

territorial governor. From the division of the Louisiana Territory in 1812 to

Missouri statehood in 1821, St. Louis was the capital of the Missouri

Territory. St. Louis’ population grew slowly after the Louisiana Purchase. Yet,

the expansion increased desire to incorporate St. Louis as a town. This allowed

it to create local ordinances without the approval of the territorial

legislature. On November 27, 1809, the first Board of Trustees was elected. The

Board passed slave codes. It formed a volunteer fire department. It also formed

an overseer to improve street quality. The Board enforced the town ordinances

by creating the St. Louis Police Department and a town jail was established in

the fortifications built for the Battle of St. Louis. After the end of the War

of 1812, the population of St. Louis and the Missouri Territory began expanding

quickly. During this expansion, land was donated for the Old St. Louis County

Courthouse. The population increase stirred interest in statehood for Missouri.

By 1820, Congress passed the disgraceful Missouri Compromise. This authorized

Missouri admission as a slave state, which was evil. The state constitutional convention

and first General Assembly met ion St. Louis in 1820. St. Louis was

incorporated as a city on December 9, 1822. The first mayor the St. Louis was

William Carr Lane. He was a Board of Aldermen, who replaced the earlier Board

of Trustees. Early city government focused on improvements to the riverfront

and health conditions. There was a street paving program and the aldermen voted

to rename the streets.

After the transfer of Louisiana to the United States, the

Spanish ended subsidies to the Catholic Church in St. Louis. As a result of

this, Catholics in St. Louis had no resident priest until the arrival of Louis

Williams Valentine Dubourg in early January 1818. When he arrived in St. Louis,

he replaced the original log chapel with a brick church, recruited priests, and

established a seminary. By 1826, a separate St. Louis diocese was created.

Joseph Rosati became the first bishop in 1827. Protestants had received

services from itinerant ministers in the late 1790’s, but the Spanish required

them to move into American territory until after the Louisiana Purchase. After

the purchase, the Baptist missionary John Mason Peck built the first Baptist

church in St. Louis in 1818. Methodist ministers reached town during the early

years after the purchase, but only formed a congregation in 1821. The

Presbyterian Church in St. Louis began as a Bible reading society in 1811 and

in December 1817 members organized a church and built a chapel late the next

year. A fourth Protestant group who took root was the Episcopal Church, founded

in 1825. During the 1830s and 1840s, other faith groups also came to St. Louis,

including the first Jewish congregation in the area, the United Hebrew

Congregation, which was organized in 1837. Followers of Mormonism arrived in

1831, and in 1854, they organized the first LDS church in St. Louis. Despite

these events, during the pre-Civil War era most of the population were

culturally Catholic or uninterested in organized religion.

St. Louis back then focused on the fur trade. Operations in

St. Louis involving this trade were led by the Chouteau family and its alliance

with the Osages and by Manuel Lisa and his Missouri Fur Company. Due to its

role as a major trading post, the city was the departure point of the Lewis and

Clark Expedition in 1804. American and other immigrant families began arriving

in St. Louis and opening new businesses. These businesses were printing and

banking which started in the 1810’s. Among the printers were Joseph Charless.

He published the first newspaper west of the Mississippi, the Missouri Gazette

on July 12, 1808. In 1816 and 1817, groups of merchants formed the first banks

in town, but mismanagement and the Panic of 1819 led to their closure. The

effect of the Panic of 1819 and subsequent depression did slow commercial

activity in St. Louis until the mid-1820’s. St. Louis businesses started to

recover by 1824 and 1825. This was done largely as a product of the

introduction of the steamboat. It first arrived in St. Louis by August 2, 1817.

Its name was the Zebulon M. Pike. Rapids north of the city made St. Louis the

northernmost navigable port for many large riverboats and the Pike and other

ships soon transformed St. Louis into a massive inland port. More goods became available in St. Louis

during the economic recovery. This was because of the new steamboat power.

Wholesalers, new banks, and other retail stores opened starting during the late

1820’s and early 1830’s. The fur trade was a big industry in the area into the

1830’s. By 1822, Jedediah Smith joined William H. Ashley’s St. Louis fur

trading company. Smith would later be known for his explorations of the West

and for being the first European American to travel overland to California. New

fur trade companies like the Rocky Mountain Fur Company pioneered trails west.

Although beaver fur lost its popularity in the 1840’s, St. Louis continued as a

hub of buffalo hide and other furs.

There was the

construction of the County Courthouse during the late 1820’s. St. Louis grew in

an addition of western lots to Ninth Street and a new Hall adjacent to the

river in 1833. The military post far north of the city at Fort Bellefontaine

moved nearer to the city to Jefferson Barracks in 1827, and the St. Louis

Arsenal was built in south St. Louis the same year. The 1830s included dramatic

population growth: by 1830, it had increased to 5,832 from roughly 4,500 in

1820. By 1835, it reached 8,316, doubled by 1840 to 16,439, doubled again by

1845 to 35,390, and again by 1850 to 77,860. The rapid population growth in

part caused cholera to be a significant problem in St. Louis. By 1849, there

was a major cholera epidemic that killed nearly 5,000 people. This caused the

creation of a new sewer system and the draining of a mill pond. Cemeteries were

removed to the outskirts of Bellefontaine Cemetery and Calvary Cemetery to

reduce groundwater contamination. In the same year, a large fire broke out on a

steamboat on the levee. It spread to 23 other boats. It destroyed a large

section of the city. The St. Louis landing was significantly improved during

the 1850’s. Using the engineering planning of Robert E. Lee, levees were

constructed on the Illinois side to direct water toward Missouri to eliminate

sand bars that threatened the landing. Another infrastructure improvement was

the city's water system, which was begun in the early 1830s and was continually

improved and expanded in the 1840’s and 1850’s.

By the 1810’s, most

early St. Louisans were illiterate. Many wealthy merchants purchased books for

private libraries. Early St. Louis schools were fee based. Most of them

conducted lessons in French. The first substantial educational effort came

about under the authority of the Catholic Church. By 1818, it opened Saint

Louis Academy, later renamed Saint Louis University. In 1832, the college

applied for a state charter, and in December 1832, it became the first

chartered university west of the Mississippi River. Its medical school opened

in 1842, with faculty that included Daniel Brainard (founder of Rush Medical

College), Moses Linton (founder of the first medical journal west of the

Mississippi River in 1843), and Charles Alexander Pope (later president of the

American Medical Association). However,

the university primarily catered to seminary students rather than the general

public, and only in the 1840's did the Catholic Church offer large scale

instruction at parochial schools. In

1853, William Greenleaf Eliot founded a second university in the city –

Washington University in St. Louis.

During the 1850's Eliot founded Smith Academy for boys and Mary Institute

for girls, which later merged and became Mary Institute and St. Louis Country

Day School.

Public education in St. Louis back then was provided by the

St. Louis Public Schools. It started in 1838. They had 2 elementary schools. The

system expanded greatly during the 1840’s. By 1854, the system had 27 schools

and served almost 4,000 students. It opened a high school to fanfare by 1855.

The high school was called Central VPA High School. It was the first public

high school west of the Mississippi River. In 1860, nearly 12,000 students had

enrolled in the district. The district also opened a normal school in 1857,

which later became Harris-Stower State University. Entertainment options

increased during the pre-Civil War period. In early 1819, the first theater

production was opened in St. Louis. There was a musical accompaniment too. In

the late 1830’s, a 35 member orchestra briefly played in St. Louis and in 1860,

another orchestra opened that played more than 60 concerts throughout 1870.

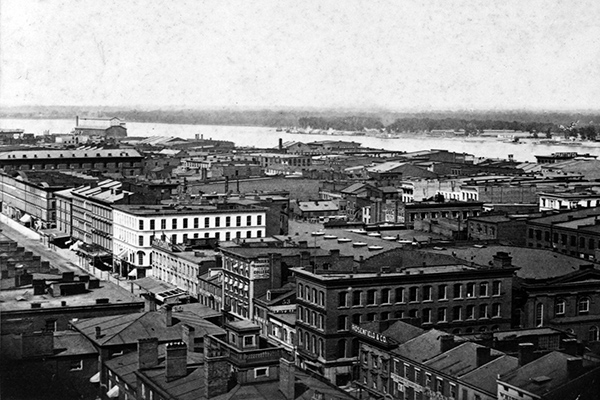

The image to right shows the Commercial District, St. Louis, Missouri. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Civil War

Before the Civil War, Missouri was a slave state. By the

1840’s, the number of slaves increased, but their percentage relative to the

population declined. During the 1850’s, both the number and percentage

declined. There were about 3,200 free black people and slaves living in St.

Louis in 150. They worked domestic servants, artisans, crew on the riverboats

and stevedores. Some slaves were allowed to earn wages and some were able to

save money to purchase their freedom or that of their relatives. Others were

manumitted, which happened more frequently in St. Louis than in the surrounding

rural area. Others tried to escape via the Underground Railroad or attempted to

gain their freedom via freedom suits. The first freedom suit in St. Louis was

filed by Marguerite Scypion in 1805. More than 300 suits were filed in St.

Louis before the Civil War. Among the most famous case was that of Dred Scott

and his wife Harriet. This was a case heard at the Old Courthouse. The suit was

based on their having traveled and lived with their slave-owner in free states.

Although the state ruled in his favor, an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court

resulted in an 1857 ruling against them. The court ruled that slaves could not

be counted as citizens, which is a racist decision.

The ruling overturned the basis of the Missouri Compromise and it inflamed national debates about slavery. Economic expansion of the 1830’s caused Irish and Germany immigrants to come into St. Louis in a higher level. The writings of Gottfried Duden encouraged German immigration. Many Irish were motivated by the Irish potato famine of 1845-1846. There was the failed Irish uprising of 1848 too. Other Irish settlers came because of St. Louis’ reputation as a Catholic city. Nativist sentiment increased in St. Louis during the late 1840’s. Nativism is bigotry against an immigrant. There were mob attacks and riots in 1844, 1849, and 1852 over nativist views. The 1844 riots derived from popular outrage and resentment toward human dissection, which was then taking place at the Saint Louis University Medical College. The discovery of human remains prompted rumors of grave robbing, and a mob of more than 3,000 residents attacked the medical college, destroying most of its interior facilities. The worst nativist riot in St. Louis took place in 1854. The local militia was used to end the fighting. 10 people were killed, 33 wounded, and 93 buildings were damaged. Regulations on elections prevented fighting in future elections in 1856 and 1858.

The ruling overturned the basis of the Missouri Compromise and it inflamed national debates about slavery. Economic expansion of the 1830’s caused Irish and Germany immigrants to come into St. Louis in a higher level. The writings of Gottfried Duden encouraged German immigration. Many Irish were motivated by the Irish potato famine of 1845-1846. There was the failed Irish uprising of 1848 too. Other Irish settlers came because of St. Louis’ reputation as a Catholic city. Nativist sentiment increased in St. Louis during the late 1840’s. Nativism is bigotry against an immigrant. There were mob attacks and riots in 1844, 1849, and 1852 over nativist views. The 1844 riots derived from popular outrage and resentment toward human dissection, which was then taking place at the Saint Louis University Medical College. The discovery of human remains prompted rumors of grave robbing, and a mob of more than 3,000 residents attacked the medical college, destroying most of its interior facilities. The worst nativist riot in St. Louis took place in 1854. The local militia was used to end the fighting. 10 people were killed, 33 wounded, and 93 buildings were damaged. Regulations on elections prevented fighting in future elections in 1856 and 1858.

Before the Civil War, the core of St. Louis leadership

shifted from the Creole and Irish families to a new group. This group was

dominated by anti-slavery Germans. Among this new class of leaders was Frank P.

Blair Jr. He led an effort to create a local militia loyal to the Union after Missouri

Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson hinted about secession. The local militia allied

itself with the Union army forces at Jefferson Barracks under the leadership of

Nathaniel Lyon. On May 10, 1861, Lyon cleared a Confederate encampment outside

the city in which would become known as the Camp Jackson Affair. While the

Confederates were being marched back into town, a group of citizens attacked

the Union and militia forces, costing 28 civilian lives. Throughout the

entirety of the Civil War, St. Louis was under pressure as it was considered a

city on the borderline. Though many people were confident in abolition, many

were concerned about the economic effect of losing their free work force. In

addition, St. Louis was still a developing city, and so a war could lead to

utter destruction and ruin. However, with all the necessity of ammunition, St.

Louis survived and transformed into a leader among cities.

After the Camp Jackson Affair, there were no more military

threats to Union control until 1864, although guerrilla activity continued in

rural areas for the duration of the war. Union General John C. Frémont placed

the city under martial law in August 1861 to suppress sedition; after Fremont's

dismissal, Union army forces continued to suppress pro-Confederate demonstrations.

The war significantly damaged St. Louis commerce, especially after the

Confederacy blockaded the Mississippi shutting off St. Louis's connection to

eastern markets. War also slowed growth during the 1860s, with an increase of

only 43,000 residents from 1860 to 1866.

Its Growth

After 1866, St. Louis

experienced rapid growth. St. Louis increased so much that it became the fourth

largest city in America back then after New York City, Philadelphia, and

Chicago. St. Louis grew its infrastructure fast. Its transportation and heavy

industry grew. During the Civil War, the infrastructure of St. Louis suffered

because of neglect. There was another cholera epidemic in 1866 and typhoid

fever existed in areas. That cholera epidemic killed more than 3,500 people.

This caused the forming of the St. Louis Board of Health. This organization

gave power to create and enforce sanitary regulation and monitor the actions of

many polluting industries. There was a new waterworks being formed in north St.

Louis in 1871 in order to hand water problems. There was a large reservoir at

Compton Hill and a standpipe at Grand Avenue. Yet, water quality problems

existed due to high demand and the dumping of waste upriver from the

waterworks. The gas light system also saw improvements during the 1870’s when

the Laclede Gaslight Company was formed to serve the south side of the city. By

the early 1870’s, new industries grew in St. Lois. There was the cotton

compressing devises which used raw cotton to be compressed for easier shipment.

By 1880, St. Louis had the third largest raw cotton market in America. Most of

it was transported by railroad. The Cotton Belt Railroad (which was created in

St. Louis in 1879) from smaller lines that connected the region to cotton

producers in Texas. St. Louis’ parks grew in St. Louis from the 1860’s to the

1870’s. Lafayette Park existed in 1868 and Tower Grove Park existed in 1868 (by

Henry Shaw donating land). One park in 1876 was said to be integrated, but Jim

Crow laws restricted the use of the park by African Americans.

After the Civil War, property values were used to fund

schools. School taxes increased. Public and parochial school expanded from

24,347 students in public schools and 4,362 students in parochial schools. By

the 1870’s, William Torrey Harris’s discipline and curriculum focused on

rigorous obedience and training in grammar, philosophy, and mathematics was

adopted by St. Louis schools. Harris also promoted kindergarten in America.

Susan Blow promoted it in 1874. Kindergarten back then was very popular in St.

Louis. It served about 7,800 students by the end of the 1870’s. Segregated

schools for African Americans started in the 1820’s by ministers John Mason

Peck and John Berry Meachum. Yet, these schools were closed by the local

police. Local black churches opened schools since they ran them secretly and

Missouri legislature banned education for free black people in St. Louis before

the Civil War. Starting in 1864, an integrated group of St. Louisans formed the

Board of Education for Colored Schools, which established schools without

public finances for more than 1500 pupils in 1865.

Black people fought for black high schools to be funded like Sumner High School. That was the first high school for black stude4nts west of the Mississippi. Inequality remained rampant in St. Louis schools. The Missouri Constitution of 1865 required municipalities to support black education; in response, the St. Louis Board of Education appropriated .2% of its budget for that purpose. However, this sum amounted to $500, meaning that facilities were quite poor; long walking distances from schools were common, and teacher salaries were roughly half of those in white schools. Railroads grew in St. Louis too. James B. Eads was a self-taught engineer who built structures like the bridge from the Missouri side. The Eads Bridge was finished in 1874, which was the first Mississippi River Bridge to St. Louis. Union Station was built in 1894 to promote railroad service in St. Louis. By December 1876, there was the separation of St. Louis from St. Louis County. This made St. Louis an independent city.

Black people fought for black high schools to be funded like Sumner High School. That was the first high school for black stude4nts west of the Mississippi. Inequality remained rampant in St. Louis schools. The Missouri Constitution of 1865 required municipalities to support black education; in response, the St. Louis Board of Education appropriated .2% of its budget for that purpose. However, this sum amounted to $500, meaning that facilities were quite poor; long walking distances from schools were common, and teacher salaries were roughly half of those in white schools. Railroads grew in St. Louis too. James B. Eads was a self-taught engineer who built structures like the bridge from the Missouri side. The Eads Bridge was finished in 1874, which was the first Mississippi River Bridge to St. Louis. Union Station was built in 1894 to promote railroad service in St. Louis. By December 1876, there was the separation of St. Louis from St. Louis County. This made St. Louis an independent city.

St. Louis industrialized heavily in brewing, flour milling,

slaughtering, machining, and tobacco processing. Paint, bricks, bag, and iron

were other industries in St. Louis. The city grew during the 1880’s in its

population from 350,518 to 451,770, making it the country's fourth largest

city; it also was fourth measured by value of its manufactured products, and

more than 6,148 factories existed in 1890. The Panic of 1893 slowed

manufacturing. The beer industry is historically known to be in existence in

St. Louis. The two largest St. Louis brewers, Anheuser-Busch (the world's

largest brewery) and Lemp Brewery, together produced 1.5 million barrels in

1900. St. Louis breweries also were innovators: Anheuser-Busch pioneered

refrigerated railroad cars for beer transport and was the first company to

market pasteurized bottled beer. There was pollution as a product of rapid

industrialization. Many people

complained to the St. Louis Board of Health about decaying animals converted to

products. There were noxious fumes being health hazards. One of the few health

policies to be carried out began in 1880; in the new policy, nuisance

regulations would be enforced strictly in some areas while little in others,

thereby encouraging offending industries to concentrate in certain areas.

Skyscrapers existed in 1892 with the Wainwight Building. Nikola Tesla conducted

a public demonstration of his wireless lighting and power transmission system

here in 1893. Addressing the National Electric Light Association, he showed

"wireless lighting" in 1893 via lighting Geissler tubes wirelessly.

Tesla proposed this wireless technology could incorporate a system for the

telecommunication of information.

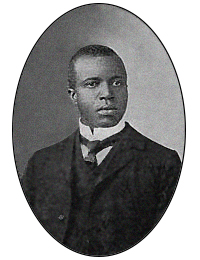

Ragtime composer Scott Joplin lived in St. Louis from 1901

to 1907. Blues music was found all over St. Louis. The home Joplin rented in

1900-1903 was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1976 and was saved

from destruction by the local African American community. In 1983, the Missouri

Department of Natural Resources made it the first state historic site in

Missouri dedicated to the African American heritage After the Civil War,

baseball was played. The baseball team the St. Louis Brown Stockings was

founded in 1875. The Brown Stockings were a founding member of the National

League and became a hometown favorite, defeating the Chicago White Stockings

(later the Chicago Cubs) in their opener on May 6, 1875. However, the original

Brown Stockings club closed in 1878, and an unrelated National League team with

the same name was founded in 1882. This team changed its name multiple times,

shortening to the Browns in 1883, then becoming the Perfectos in 1899, and

settling on the St. Louis Cardinals in 1900. The 1904 World’s Fair took place

in St. Louis. This comes 100 years after the Louisiana Purchase. The Government

Building at the 1904 World’s Fair was held in St. Louis Forest Park. The

infrastructure of St. Louis was modernized to make way for the World’s Fair.

The fair celebrated American expansionism, which is a coded phrase for American

imperialism. It showed exhibits of French fur trading and Eskimo including

Filipino villages. Concurrently, the 1904 Summer Olympics were held in St. Louis,

at what would become the campus of Washington University in St. Louis.

Historical artifacts relating to St. Louis history were collected and exhibited

by the Missouri Historical Society.

The early 20th century

During the early 1900’s, segregation continued. There were

massive building programs. It involved developing residential neighborhoods and

growing parks and playgrounds. The Parks Commissioner and former professional

tennis player Dwight F. Davis continued to develop recreational locations. By the

early 1910’s, he expanded tennis locations. There was a public 18 hole golf

course in northwest Forest Park. The St. Louis Zoo existed during the 1910’s

under the leadership of Mayor Henry Keil. The 1939 smog in St. Louis caused the

ban on burning low quality coal back in December 1939. There was natural gas to

heating homes and cleaner fuels in existence by the 1940’s. The 1904 St. Louis

World Fair saw ballooning. The first airplane in St. Louis that flew was in

1909. More airfields existed. In 1925, Lambert Field expanded its facilities.

The St. Louis primary airport today is Lambert Field. Jim Crow laws existed in

St. Louis. Racism was prevalent just like in the American South. The St. Louis

black community continued to work and fight for justice. They lived along the

riverfront or near the railroad yards. Due to an influx of refugees from East

St. Louis and the general effects of the Great Migration of blacks from the

rural South to industrial cities, the black population of St. Louis increased

more rapidly than the whole during the decade of 1910 to 1920. Many St. Louis

German and Irish communities wanted neutrality when World War I commenced in

1914. Many Americans back then mistreated German St. Louisans because of the

war. Some St. Louisans repressed elements of German culture. Many plants were

closer to the Atlantic back then. After World War I, the nationwide prohibition

of alcohol in 1919 brought heavy losses to the St. Louis brewing industry.

Other industries, such as light manufacturing of clothing, automobile

manufacturing, and chemical production, filled much of the gap, and St. Louis's

economy was relatively diversified and healthy during the 1920’s. St. Louis

suffered as much or more than comparable cities in the early years of the Great

Depression. Manufacturing output fell by 57 percent between 1929 and 1933,

slightly more than the national average of 55 percent, and output remained low

until World War II. Unemployment during the Depression was high in most urban

areas, and St. Louis was no exception (see table). Black workers in St. Louis,

as in many cities, suffered significantly higher unemployment than their white

counterparts. To aid the unemployed, the city allocated funds starting in 1930

toward relief operations. In addition to city relief aid, New Deal programs

such as the Public Works Administration employed thousands of St. Louisans.

Civic improvement construction jobs also reduced the number of persons on

direct relief aid by the late 1930’s.

World War II and the suburbs

St. Louis has a big

role in World War II. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. St. Louis

later prepared for war. They sent soldiers to protect local military and

munitions installations. These installations include the St. Louis Army

Ammunition Plant at Goodfellow and Bircher, Lambert Field, and the

Curtiss-Wright aircraft factory. The St. Louis police protect bridges. Workers

in military factories were checked to protect against sabotage. There were

anti-civil liberty measures where there was the arrest or interrogation of

German, Italian, and Japanese persons including naturalized citizens. Many

local Japanese restaurants were closed, which was wrong. One Japanese man, who

was the manager of the Bridlespur Hunt Club in Huntleigh, Missouri, was arrested.

St. Louis labor leaders created boycotts of products created by the Axis Power.

Bonfires were lit of Japanese made products. During the spring and summer of

1942, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) made several high-profile

arrests or investigations in St. Louis, including one into a pastor in

Chesterfield, Missouri who was accused of sedition for condemning lynchings and

openly opposing the playing of the Star Spangled Banner in church. So, the FBI

back then was attacking the freedom of speech. There was anti-Japanese racist

sentiment throughout America during this time. Much money came to build up

defense systems and infrastructure like bridges. The city had its first

blackout on March 7, 1942. A second blackout, held in February 1943, was considerably

more successful than the first, with 4 of 12 civil defense districts fully

blacked out. The local branch of the federal Office of Civilian Defense

enrolled 5,300 air raid wardens, 2,400 volunteer firefighters, and 3,000

volunteer police officers by April 1942. City building inspectors selected 200

sites as air raid shelters, enough to house 40,000 people, and local schools

began preparing students for attack. The city and region also were protected by

anti-aircraft guns, but mistakenly fired on civilian aircraft multiple times

during the war. Atomic bomb research existed in St. Louis too.

Many vehicles that were used in the invasion of Normandy were created by the St. Louis Chevrolet factory. Many soldiers from St. Louis participated in World War II. One was Edward O’Hare. He grew up in St. Louis. He attended Western Military Academy in Alton, Illinois, followed by acceptance to the United States Naval Academy. During a combat flight in the Pacific in February 1942, O'Hare shot down five Japanese bombers that were on a run to attack the USS Lexington, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor and a parade in St. Louis. St. Louis also was home to Wendell O. Pruitt, an African-American pilot who shot down three enemy aircraft and multiple ground targets in June 1944. St. Louis celebrated Pruitt's achievement by naming December 12, 1944 "Captain Wendell O. Pruitt Day.” In addition, more than 5400 St. Louisans became casualties of the war, listed as either missing in action or killed in action. Products were rationed in St. Louis. The supplies rationed included tires, gasoline, and other material. St. Louis was the first U.S. city to have its war bond quota reached in 1942 and 1943. At the outbreak of war, African-American St. Louisans gained greater acceptance in industry than they had previously.

By the end of 1942, nearly 8,000 black men and women were hired in St. Louis industries, but employment discrimination remained a significant problem for the community. Most jobs in war factories were unskilled, although some factories, notably Scullin Steel, hired significant numbers of skilled black workers. The April 1943 municipal elections were significant for the civil rights movement, as the first African-American was elected to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, Rev. Jasper C. Caston. In the same election, the first woman was elected to the Board, Clara Hempelmann. African Americans were allowed to eat at a city owned lunch counters in March of 1944. This came as a product of a city integration ordinance. St. Louis admitted its first black students in the fall of 1944 in St. Louis University. There was a sit in on May 18, 1944 to protest the black sailor being refused service in a downtown lunch counter. Other peaceful sit-ins were at Stix, Baer, and Fuller. Protesters were removed. Jim Crow didn’t end, but it was the start of the end of Jim Crow in St. Louis. Many German prisoners of war were in St. Louis and Italians in Weingarten, Missouri. They held with flooding preventing measures in Mississippi. After World War II ended, the American Legion was created in St. Louis. Many St. Louis people lost their jobs. There were economic problems. The GI Bill helped veterans own homes in St. Louis and St. Louis County. Later, there was a population exodus from St. Louis City. More people lived in the suburbs and St. Louis’ population declined.

Many vehicles that were used in the invasion of Normandy were created by the St. Louis Chevrolet factory. Many soldiers from St. Louis participated in World War II. One was Edward O’Hare. He grew up in St. Louis. He attended Western Military Academy in Alton, Illinois, followed by acceptance to the United States Naval Academy. During a combat flight in the Pacific in February 1942, O'Hare shot down five Japanese bombers that were on a run to attack the USS Lexington, for which he was awarded the Medal of Honor and a parade in St. Louis. St. Louis also was home to Wendell O. Pruitt, an African-American pilot who shot down three enemy aircraft and multiple ground targets in June 1944. St. Louis celebrated Pruitt's achievement by naming December 12, 1944 "Captain Wendell O. Pruitt Day.” In addition, more than 5400 St. Louisans became casualties of the war, listed as either missing in action or killed in action. Products were rationed in St. Louis. The supplies rationed included tires, gasoline, and other material. St. Louis was the first U.S. city to have its war bond quota reached in 1942 and 1943. At the outbreak of war, African-American St. Louisans gained greater acceptance in industry than they had previously.

By the end of 1942, nearly 8,000 black men and women were hired in St. Louis industries, but employment discrimination remained a significant problem for the community. Most jobs in war factories were unskilled, although some factories, notably Scullin Steel, hired significant numbers of skilled black workers. The April 1943 municipal elections were significant for the civil rights movement, as the first African-American was elected to the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, Rev. Jasper C. Caston. In the same election, the first woman was elected to the Board, Clara Hempelmann. African Americans were allowed to eat at a city owned lunch counters in March of 1944. This came as a product of a city integration ordinance. St. Louis admitted its first black students in the fall of 1944 in St. Louis University. There was a sit in on May 18, 1944 to protest the black sailor being refused service in a downtown lunch counter. Other peaceful sit-ins were at Stix, Baer, and Fuller. Protesters were removed. Jim Crow didn’t end, but it was the start of the end of Jim Crow in St. Louis. Many German prisoners of war were in St. Louis and Italians in Weingarten, Missouri. They held with flooding preventing measures in Mississippi. After World War II ended, the American Legion was created in St. Louis. Many St. Louis people lost their jobs. There were economic problems. The GI Bill helped veterans own homes in St. Louis and St. Louis County. Later, there was a population exodus from St. Louis City. More people lived in the suburbs and St. Louis’ population declined.

German Jewish immigrants, who had mainly come to St. Louis

in the decades after the Civil War, began moving to wealthy west end of St.

Louis, while Eastern European Jewish immigrants began moving to areas in

northwest St. Louis and into Wellston and University City, Missouri. Italians

at first had congregated in a "Little Italy" located in the Columbus

Square neighborhood, but starting in the 1910s and 1920s large numbers of

Italians (primarily from Milan, Lombardy, and Piedmont) began moving to an area

west of Kings highway and south of Forest Park, known as The Hill. This area,

five miles from downtown, was distant enough from the city that the group

maintained cultural identity and was relatively self-sufficient. After World

War II, the neighborhood fell into decline, but it was revitalized through a

neighborhood association effort starting in 1969 and remains an icon of

Italian-American culture in St. Louis. Streetcars and railroad stations allowed

more people to go into the suburbs. The suburbs developed with the national

highway system and more people living from the Rust Belt (in the Northeast and

Midwest) to the Sunbelt (in the south and west). The increase of automobile

ownership caused suburbanization to grow too.

St. Louis' Civil Rights Movement

The long, unsung history of St. Louis’ Civil Rights Movement

shows the inspirational power of black Americans. Since the founding of St.

Louis in 1764, many people of black African descent were in St. Louis. Many

were slaves and many were free black people. Back during French and Spanish

colonial rule, black people lived in St. Louis. Many black settlers defended

St. Louis from the British during the Revolutionary War during the Battle of

Fort San Carlos. This took place on the Gateway Arch grounds. There were 10,000

slaves in Missouri by 1820. Many people opposed the disgraceful 1821 Missouri

Compromise. There was a protest among free black people and white people

against Missouri being a slave state back in 1819 (according to Judge Nathan B.

Young). It is also very important to mention that Dred Scott lived in St.

Louis. His wife stood by him and he was free before he passed away in September

of 1858. His wife Harriet Scott lived to the time of June 17, 1876. Rev. John

Berry Meachum helped to educate black children during the 19th century. One

Freedom School teacher was a black woman named Elizabeth Keckley. She purchased

her freedom in 1854. She wrote about her experiences in her book entitled,

“Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slaves, and Four Years in the White

House.” She was a seamstress in the White House, who created dresses for Mary

Todd Lincoln (or Abraham Lincoln’s wife).

Many black people owned land in St. Louis throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Ester was a black woman who owned land. James Milton Turner was born a slave in St. Louis and he was freed as a child with his mother in 1843. He attended Oberlin College in Ohio (which was a famous college where African Americans graduated from back then) and, after the Civil War, became secretary of the Missouri Equal Rights League, campaigning to give blacks the right to vote. In 1870, Missouri accepted the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing the right to vote. Turner died in 1915 and is buried in Father Dickson Cemetery in Crestwood. Josephine Baker was born in St. Louis and she fought for civil rights throughout her life. She was raised in the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood of St. Louis.

Many black people owned land in St. Louis throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Ester was a black woman who owned land. James Milton Turner was born a slave in St. Louis and he was freed as a child with his mother in 1843. He attended Oberlin College in Ohio (which was a famous college where African Americans graduated from back then) and, after the Civil War, became secretary of the Missouri Equal Rights League, campaigning to give blacks the right to vote. In 1870, Missouri accepted the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, guaranteeing the right to vote. Turner died in 1915 and is buried in Father Dickson Cemetery in Crestwood. Josephine Baker was born in St. Louis and she fought for civil rights throughout her life. She was raised in the Mill Creek Valley neighborhood of St. Louis.

The African American-based St. Louis American newspaper was

created by Judge Nathan B. Young and other African American businessmen

(including Homer G. Phillips). It dealt with black issues and it was first

published in 1928. It has won many awards in excellence involving journalism,

design, and commitment to the community. There were the white terrorists who

murdered and brutalized black people in the 1917 East St. Louis riots (in Illinois). Many

black people fled into St. Louis via the bridges. The riot caused 39 black

people to die and 9 whites to die too. In 1930, the St. Louis American

newspaper started a "Buy Where You Can Work" campaign. This campaign

was about both boycotting businesses that discriminated against black people

and forming more economic empowerment in the African American community. Judge

Nathan B. Young edited issues in the newspaper for decades. The newspaper gave

people great information about African American contributions in St. Louis and

the contributions of non-black people in the freedom struggle.

During the 1930’s, black people in the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters fought for labor rights. One African American union organizer and politicians involved in this effort was Theodore McNeal. He was the first elected African American to be in the Missouri Senate after he defeated Edward Hogan. He led the passage of the Fair Employment Practices Act in 1962. He supported the creation of the University of Missouri-St. Louis in 1964 and he helped to establish the passage of the state Civil Rights Code in 1965. He worked in the University of Missouri and received many honors and honorary degrees (from the University of Missouri, Lincoln University, and Lindenwood University). He lived and passed away on October 25, 1982. He or McNeal said the following words decades ago at the Kiel Auditorium rally: “We resent the Jim Crow setup in the armed forces and war industry, and treatment branding us as second-class citizens,”

During the 1930’s, black people in the International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters fought for labor rights. One African American union organizer and politicians involved in this effort was Theodore McNeal. He was the first elected African American to be in the Missouri Senate after he defeated Edward Hogan. He led the passage of the Fair Employment Practices Act in 1962. He supported the creation of the University of Missouri-St. Louis in 1964 and he helped to establish the passage of the state Civil Rights Code in 1965. He worked in the University of Missouri and received many honors and honorary degrees (from the University of Missouri, Lincoln University, and Lindenwood University). He lived and passed away on October 25, 1982. He or McNeal said the following words decades ago at the Kiel Auditorium rally: “We resent the Jim Crow setup in the armed forces and war industry, and treatment branding us as second-class citizens,”

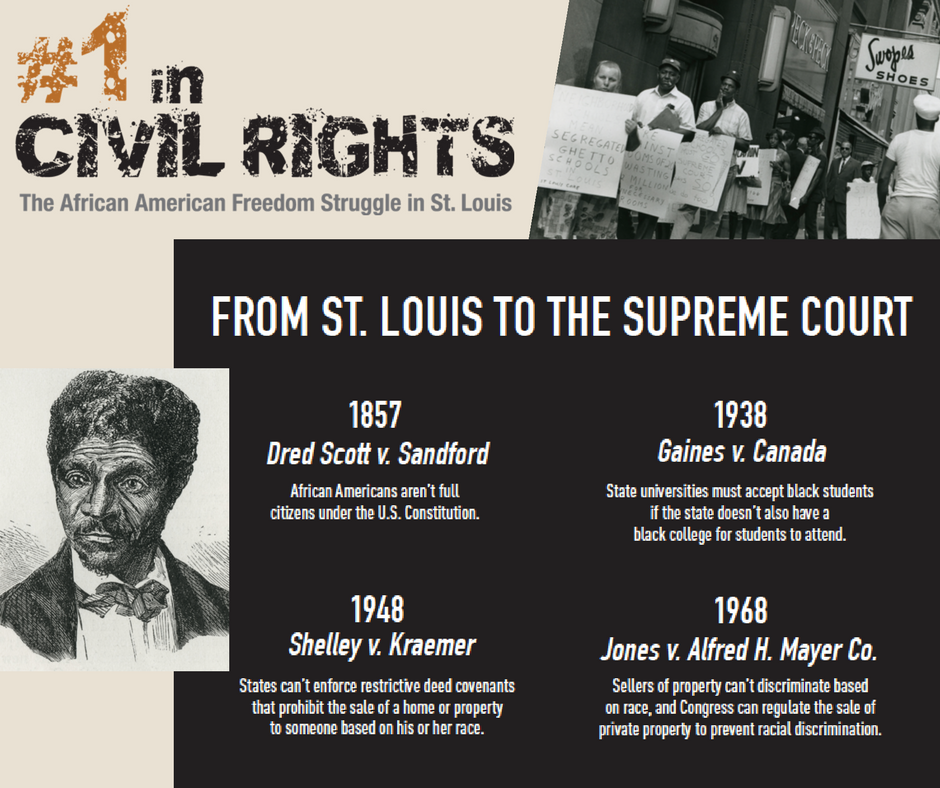

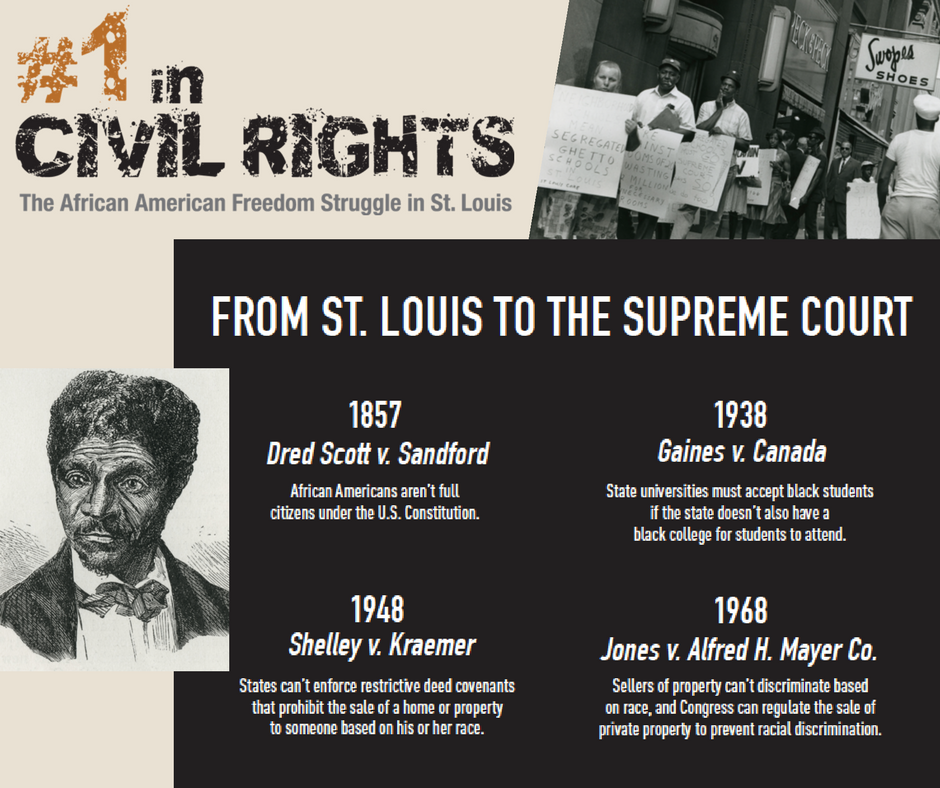

The Civil Rights Movement in St. Louis involved heavily

grassroots activism. It involved men, women, and children who wanted an end to

racial discrimination, Jim Crow, housing discrimination, and economic

exploitation. They wanted black people to have adequate, fair job

opportunities, so people can pursue their happiness in the most effective way

possible. Many important civil rights cases were reality to the city of St.

Louis. The Missouri History Museum documents the African American Freedom

Struggle in St. Louis. The civil rights movement was very active in St. Louis.

The 1938 Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada Supreme Court decision stated that

states that provide a school to whites must also provide in state education to

black people too. The Supreme Court said that this can occur by either allowing

black people and white people to attend the same school or create a second

school for African Americans. Lloyd Gaines was a black man who wanted to go

into law school. He was refused to do so in Missouri. So, Gaines cited the

Fourteenth Amendment as evidence to why his preventing of going into a law

school was a violation of his constitutional rights. He’s right. The decision

did not quite strike down separate but equal facilities, upheld in Plessy v.

Ferguson (1896).

Instead, it provided that if there was only one school, students of all races could be admitted. It struck down segregation by exclusion if the government provided just one school. That was a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education (1954). This case was the beginning of the end of the Plessy decision. Despite the initial victory claimed by the NAACP, after the Supreme Court had ruled in Gaines' favor and ordered the Missouri Supreme Court to reconsider the case, Gaines was nowhere to be found. When the University of Missouri soon after moved to dismiss the case, the NAACP did not oppose the motion. The historic Shelley v. Kraemer (of 1948) case was a landmark Supreme Court case that ruled that courts could not enforce racial covenants on real estate. Louis and Fern Kraemer were white neighbors who wanted to keep the black couple (J.D. and Ethel Shelley) from owning a home in the area. George L. Vaughn was a black attorney who represented J.D. Shelley at the Supreme Court of the United States. The attorneys who argued the case for the McGhees (as part of the companion case McGhee v. Sipes from Detroit, Michigan, where the McGhees purchased land that was subject to a similar restrictive covenant) were Thurgood Marshall and Loren Miller. Later, the St. Louis City Hall was integrated and a swimming pool was integrated in Fairground Park.

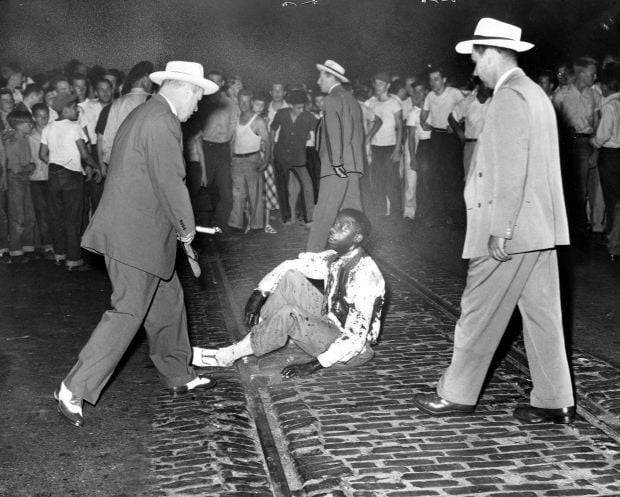

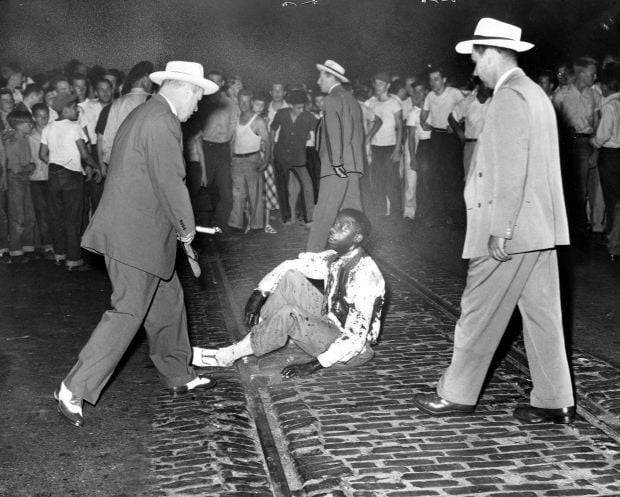

The image on the left show an innocent black person on the ground after being assaulted by white racists during the 1949 Fairground Park riot.

The June 21, 1949 Fairground Park riot involve white racists hating the fact that St. Louis integrated its public swimming pools. Robert Gammon & J.C. Tobias are black people who were chased by white racist gangs back then during the Fairgound Park riots (they were much younger back then). During that 1949 riot, about 4,000 to 5,000 whites roamed the grounds of the Fairground Park and assaulted any and every African American that crossed their path. In 1959, sit-ins took place at Pope’s Cafeteria downtown, the Woolworth’s in midtown and the Howard Johnson’s at 3501 North Kings highway. Many restaurants had conceded to integrate by 1961, when the Board of Aldermen banned discrimination in public places. The historic Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case, which held that Congress could regulate the sale of private property to prevent racial discrimination. The Supreme Court decision of Shelley v. Kraemer banned all racial discrimination, private as well as public, in the sale or rental of property, and that the statute, thus construed, is a valid exercise of the power of Congress to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. In May of 1942, the Booker T. Washington Technical vocational school wanted to help promote the war effort during WWII.

Instead, it provided that if there was only one school, students of all races could be admitted. It struck down segregation by exclusion if the government provided just one school. That was a precursor to Brown v. Board of Education (1954). This case was the beginning of the end of the Plessy decision. Despite the initial victory claimed by the NAACP, after the Supreme Court had ruled in Gaines' favor and ordered the Missouri Supreme Court to reconsider the case, Gaines was nowhere to be found. When the University of Missouri soon after moved to dismiss the case, the NAACP did not oppose the motion. The historic Shelley v. Kraemer (of 1948) case was a landmark Supreme Court case that ruled that courts could not enforce racial covenants on real estate. Louis and Fern Kraemer were white neighbors who wanted to keep the black couple (J.D. and Ethel Shelley) from owning a home in the area. George L. Vaughn was a black attorney who represented J.D. Shelley at the Supreme Court of the United States. The attorneys who argued the case for the McGhees (as part of the companion case McGhee v. Sipes from Detroit, Michigan, where the McGhees purchased land that was subject to a similar restrictive covenant) were Thurgood Marshall and Loren Miller. Later, the St. Louis City Hall was integrated and a swimming pool was integrated in Fairground Park.

The image on the left show an innocent black person on the ground after being assaulted by white racists during the 1949 Fairground Park riot.

The June 21, 1949 Fairground Park riot involve white racists hating the fact that St. Louis integrated its public swimming pools. Robert Gammon & J.C. Tobias are black people who were chased by white racist gangs back then during the Fairgound Park riots (they were much younger back then). During that 1949 riot, about 4,000 to 5,000 whites roamed the grounds of the Fairground Park and assaulted any and every African American that crossed their path. In 1959, sit-ins took place at Pope’s Cafeteria downtown, the Woolworth’s in midtown and the Howard Johnson’s at 3501 North Kings highway. Many restaurants had conceded to integrate by 1961, when the Board of Aldermen banned discrimination in public places. The historic Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), is a landmark United States Supreme Court case, which held that Congress could regulate the sale of private property to prevent racial discrimination. The Supreme Court decision of Shelley v. Kraemer banned all racial discrimination, private as well as public, in the sale or rental of property, and that the statute, thus construed, is a valid exercise of the power of Congress to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. In May of 1942, the Booker T. Washington Technical vocational school wanted to help promote the war effort during WWII.

St. Louis was very central in the development of the black

freedom struggle. Many of the unsung heroes of this struggle include Billie

Teneau, Frankie Freeman, Hedy Epstein, Percy Green II, and Jamala Rogers. By

1947, CORE or the Congress on Racial Equality was formed in its St. Louis

chapter. CORE’s original goal was to end injustice and establish true equality

for all people. Billie Teneau was a founding member of the local CORE chapter.

CORE back then held interracial picnics in Forest Park to show a message for

justice. They made peaceful demonstrations throughout the city. During this

time, the NAACP was already a powerful force in St. Louis. Its leadership was

strong. NAACP worked heavily in the courts to fight for equal educational

opportunities, racial equality, and fair housing. On 1949, NAACP civil rights

lawyer Frankie Muse Freeman was involving the Brewton v. the Board of Education

of St. Louis case. This was years before the Brown v. Board of Education

decision that banned racial segregation in public schools back in 1954. Hedy

Epstein worked with the Freedom of Residence to fight for housing rights. Percy

Green II fought for direct action in St. Louis. He was part of CORE and found

the ACTION organization to continue in nonviolent resistance. Jamala Rogers is

a known activist who fought for freedom in St. Louis for decades and in our

time with the Ferguson movement. One of the most important parts of St. Louis

history was the Jefferson Bank demonstration.

On August 30, 1963, black protesters desired changes in the

hiring practices at Jefferson Bank. Working class people, physicians, and

business professionals marched in favor of economic justice. Civil rights

groups wanted the bank to hire more black people since the bank only had two

black employees. Not to mention that St. Louis is a black mecca of culture. The

protesters sang, “We shall not be moved.” On that day of August 30, 1963, nine

people were arrested. Bank executives were stubborn as they refused to change

originally. CORE supported the movement against Jefferson Bank at 2600

Washington Avenue (just west of downtown). CORE chairman back then, Robert B.

Curtis, wanted the bank to do the right thing. CORE and the NAACP worked

together in the endeavor. The protests continued. On March 2, 1964, Jefferson

Bank hired six more African Americans. The protests represented the influence

of St. Louis in the modern civil rights movement.

The St. Louis city Alderman William Clay would go into

Congress. Raymond Howard and Louis Ford would be Missouri legislators. Hundreds

of people went into jail during the 1960’s in St. Louis for demonstrating

against Jefferson Bank. To this very day, protests involving the Jefferson Bank

continue. They also wanted many businesses to hire more black people as well.

Many people were arrested during the 1960's after the court in St. Louis issued

an injunction which would try to restrict demonstrations. Attorneys like

Margaret Bush Wilson were involved in the movement involving the Jefferson Bank

demonstrations too. She was a civil rights activist throughout her life and she

was a courageous black woman. Norman Seay continues to speak out against

discrimination and bank hiring practices. On July 14, 1964, civil rights

protesters including Percy Green climbed up the unfinished Gateway in 1964 to

fight for job opportunities for African Americans. Percy Green also rightfully

opposed economic discrimination and he wanted to fight the Veiled Prophet

parade (starting in 1965) because of its racist overtones. With the Black Power

movement, Black Panthers and other groups were readily involved in St. Louis.

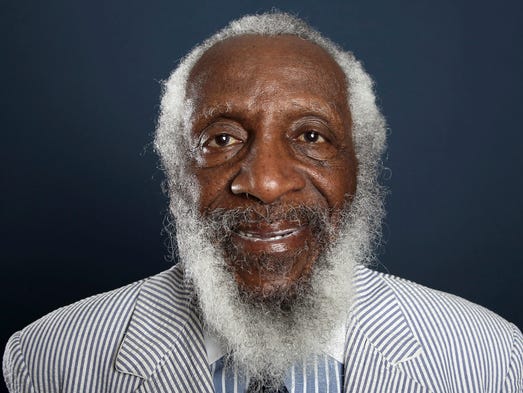

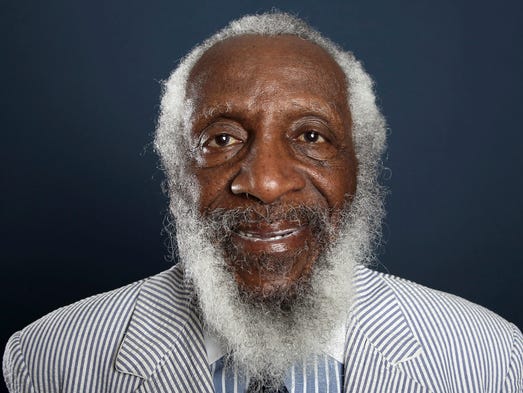

One of the greatest civil rights leaders was Dick Gregory, who was born and

raised in St. Louis. he lived for 84 years from 1932 to 2017. He supported Dr.

King and Malcolm X. He marched, protested, gave sacrifice to the cause of

freedom, and was a strong health plus peace activist. Dick Gregory opposed the

Vietnam War and he was always outspoken on critically important issues. He was

a social analyst, comedian, and great elder. The Black Panthers was a

progressive, revolutionary group who desired black liberation and Third World

international solidarity. They believed in socialist principles and desired all

power to the people. In April of 1968, Dr. King was assassinated. In that

month, 30,000 people marched peacefully to Forest Park. There was no rebellion

in St. Louis. Also, on April 4, 1969, ACTION members raised their clinched

fists in endorsing a rent strike in St. Louis.

The 1969 rent strike in St. Louis public housing brought

fair, affordable housing more into the discussion among the national civil

rights agenda. Gwen B. Giles was the first African American woman elected to

the Missouri Senate. Giles was a civil rights activist and got involved in

Democratic politics while trying to improve the lives of black people living in and

around St. Louis. She broke down barriers for black people and women in

Missouri. As co-chair of the Legislative

Black Caucus, she looked at discrimination in hiring practices. Giles sponsored

bills including endorsing the Equal Rights Amendment, eliminating blue laws,

processing personal-injury claims, making public assistance easier to deposit

for citizens, and increasing aid to dependent children of unemployed parents.

Under her leadership, the West End Community Conference in St. Louis addressed

local school desegregation and received $30 million dollars to address housing

in the area. She was a member of the Order of Women Legislators, NAACP, the

International Consultation on Human Rights, and the National Council of Negro

Women. She co-founded the Missouri Black Leadership Conference. She passed away

in 1986 as a product of lung cancer. She was 53. Dr. Joe Williams was one of

the leaders of the civil rights movement in the city during the 1960's. He

passed away on March 16, 2013 at the age of 87. Curt Flood was an African

American baseball player who fought for free agency. As time went on, more

black people migrated into the suburbs of St. Louis County including Ferguson

from 1970 to the present.

St. Louis is the fifth most segregated state in the Union today. Housing discrimination and unregulated suburban development continues in the St. Louis region to this very day. In Missouri, racial and class tensions exist and we have a long way to go. Yet, we have faith that the future will be better than the past via discussions, social activism, and the development of our power. Decades later since 1968, the Black Lives Matter movement would fight against racial oppression and police brutality during the 21st century. We are still fighting poverty, gentrification, and corporate exploitation worldwide. The events of Ferguson (with Michael Brown being killed by Darren Wilson in August of 2014) and St. Louis, involving the opposition to the police killing unarmed black people, has inspired a new generation of activism. In the end, we shall overcome.

St. Louis is the fifth most segregated state in the Union today. Housing discrimination and unregulated suburban development continues in the St. Louis region to this very day. In Missouri, racial and class tensions exist and we have a long way to go. Yet, we have faith that the future will be better than the past via discussions, social activism, and the development of our power. Decades later since 1968, the Black Lives Matter movement would fight against racial oppression and police brutality during the 21st century. We are still fighting poverty, gentrification, and corporate exploitation worldwide. The events of Ferguson (with Michael Brown being killed by Darren Wilson in August of 2014) and St. Louis, involving the opposition to the police killing unarmed black people, has inspired a new generation of activism. In the end, we shall overcome.

More St. Louis Building Projects

After World War II, there were early urban renewal actions

in St. Louis. Also, many people made an effort to create a riverfront memorial

to try to honor the slave owner Thomas Jefferson. This later would include the

famous Gateway Arch. The project started in the early 1930’s. They or

authorities acquired and demolished a 40 block area where the memorial would

stand. The only remnant of Laclede’s street grid that was preserved was north

of Eads Bridge (in what is now called Laclede’s Landing). The only building in

the area to remain was the Old Cathedral. The area was used as a parking lot

and demolition continued until the start of World War II. The project stalled

until a design competition for the memorial started. In 1948, the Finnish

architect Ero Saarinen’s design for an inverted and weighted catenary curve won

the competition. Groundbreaking started in 1954. The Arch topped out in October

of 1965.

A museum and visitors’ center was completed underneath the structure and it was opened in 1976. It attracted millions of visitors. The Arch ultimately spurred more than $500 million in downtown construction during the 1970’s and the 1980’s. There were plans during the 1930’s to build subsidized housing in St. Louis. Civil improvement efforts existed during the 1920’s. There were 2 big housing projects built in 1939. After World War II, more than 33,000 houses had shared outdoor toilets while thousands of St. Louisans lived in crowded, unsafe conditions. Starting in 1953, St. Louis cleared the Chestnut Valley area in Midtown, selling the land to developers who constructed middle-class apartment buildings. Nearby, the city cleared more than 450 acres (1.8 km2) of a residential neighborhood known as Mill Creek Valley, displacing thousands. A residential mixed-income development known as LaClede Town was created in the area in the early 1960's, although this was eventually demolished for an expansion of Saint Louis University. The majority of people displaced from Mill Creek Valley were poor and African American, and they typically moved to historically stable, middle-class black neighborhoods such as The Ville. In 1953, St. Louis issued bonds that financed the completion of the St. Louis Gateway Mall project and several new high rise housing projects.

A museum and visitors’ center was completed underneath the structure and it was opened in 1976. It attracted millions of visitors. The Arch ultimately spurred more than $500 million in downtown construction during the 1970’s and the 1980’s. There were plans during the 1930’s to build subsidized housing in St. Louis. Civil improvement efforts existed during the 1920’s. There were 2 big housing projects built in 1939. After World War II, more than 33,000 houses had shared outdoor toilets while thousands of St. Louisans lived in crowded, unsafe conditions. Starting in 1953, St. Louis cleared the Chestnut Valley area in Midtown, selling the land to developers who constructed middle-class apartment buildings. Nearby, the city cleared more than 450 acres (1.8 km2) of a residential neighborhood known as Mill Creek Valley, displacing thousands. A residential mixed-income development known as LaClede Town was created in the area in the early 1960's, although this was eventually demolished for an expansion of Saint Louis University. The majority of people displaced from Mill Creek Valley were poor and African American, and they typically moved to historically stable, middle-class black neighborhoods such as The Ville. In 1953, St. Louis issued bonds that financed the completion of the St. Louis Gateway Mall project and several new high rise housing projects.

The most famous and largest of these projects were

Pruitt-Igoe. It opened in 1954 on the northwest edge of downtown. It included

33 eleven-story buildings with nearly 3,000 units. Between 1953 and 1957, St.

Louis built more than 6,100 units of public housing. Each opened with enthusiasm

on the part of the local leaders, the media, and new tenants. The problem was

that from the beginning, the projects had too little recreational space, too

few healthcare facilities, no shopping centers, and employment opportunities

were low. Crime was rampant, especially at Pritt-Igoe. The complex was

demolished in 1975.

The other St. Louis housing projects remained relatively

occupied through the 1980’s in spite of problems of poverty, crime, and lax

health care services. So, many black people and poor people were forced to live

in bad housing. There was the 1955 urban renewal bond issue. It totaled more

than $110 million. The bonds provided funds to purchase land to build three

expressways into downtown St. Louis. It evolved into Interstate 64, Interstate

70, and Interstate 44. In 1967, the highway only Poplar Street Bridge opened to

move traffic from all three expressways over the Mississippi River. The

openings of the Arch in 1965 and the bridge in 1967 were accompanied by the

opening of a new stadium for the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cardinals moved into

Busch Memorial Stadium early in the 1966 season. Construction of the stadium

required the demolition of Chinatown, St. Louis, ending the large presence of a