Selma: 60 Years Later

The Selma, Alabama Voting Rights Movement was one of the greatest historical eras of the Modern-Day Civil Rights Movement. If anyone wants to comprehend the components of the Civil Rights Movement in a great, comprehensive fashion, that person should study the Selma movement in great detail. That history details the growth, resiliency, and strength of the Civil Rights Movement. Also, the Selma to Montgomery era saw tragedies as there were the murders of Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo, and Rev. James Reeb. This movement was about nonviolent protestors and activists using their public protests and other legitimate actions to fight for the right of African Americans to have the right to exercise their constitutional right to vote in defiance of evil, reactionary segregationist repression (which was done by a racist capitalist Southern aristocracy). This movement was part of the broader voting rights movement in America that wanted not only voting rights but an end to Jim Crow apartheid (and all forms of racial injustice). The Dallas County Voters League (DCVL), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and other organizations worked together in fighting for justice. The end of this fight caused the 1965 Voting Rights Act to be passed federally. After the Selma voting rights movement, the Civil Rights Movement changed to focus more on economic, social, and foreign policy issues, from housing rights, educational issues, health care matters, anti-Vietnam War activism, dealing with poverty, and dealing with the rebellions of the 1960s. One hundred years before the passage of the Voting Rights Act, slavery was abolished, but my black people weren't free from racism, discrimination, and oppression in general. The 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution protected many of our rights, but we weren't truly free in American society. So, the Civil Rights Movement grew using nonviolent resistance and self-defense in many cases to oppose a brutal system of tyranny. It took black people and freedom-loving people of every color to stand up and speak up for freedom to make the Selma movement successful. From Bloody Sunday to the rally in Montgomery, Alabama, the era of the Selma movement brought joy and inspiration to the human race. The sad irony is that we have fewer voting rights now in 2025 than in 1965 because of bad Supreme Court decisions and some states passing repugnant voter suppression laws. That is why we must know about this sacrosanct history and the sacrifice of heroes who were part of the Selma voting rights movement like Amelia Boynton, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Parthia Hall, Kwame Ture, John Lewis, Annie Lee Cooper, Hosea Williams, Diane Nash, James Orange, and other human beings who enthuastically loved freedom.

The Start of the Movement

The Selma voting Rights movement started over a century before the Voting Rights Act was signed in 1865. During the 19th century, Southern state legislatures passed and maintained evil Jim Crow laws. These laws disenfranchised the millions of African Americans in the South (and in some areas of the Midwest like Missouri) to advance racial segregation. By the turn of the 20th century, the Alabama state legislature passed a new constitution that totally disenfranchised most black people and many poor white people by requirements for payment of a poll tax and passing a literacy test and comprehension of the constitution. Many black people were forced out of political power with these laws passed. Selma was part of the Alabama Black Belt with a majority black population. In 1961, the population of Dallas County was 57% black, but of the 15,000 black people old enough to vote, only 130 were registered (fewer than 1%). At that time, more than 80% of Dallas County blacks lived below the poverty line, most of them working as sharecroppers, farmhands, maids, janitors, and day laborers, but there were also teachers and business owners. With the literacy test administered subjectively by white registrars, even educated black people were prevented from registering or voting. The leaders of the Selma voting rights movement included the Boynton family (Amelia, Sam, and son Bruce), Rev. L. L. Anderson, J. L. Chestnut, and Marie Foster, and the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL). They tried to register black citizens during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Their efforts were blocked by state and local officials, the White Citizens' Council, and the Ku Klux Klan. By the 1960s, county officials and the Citizens' Council used such tactics as restricted registration hours; economic pressure, including threatening people's jobs, firing them, evicting people from leased homes, and economic boycotts of black-owned businesses; and violence against black human beings who tried to register. The Society of Saint Edmund, an order of Catholics committed to alleviating poverty and promoting civil rights, were the only whites in Selma who openly supported the voting rights campaign. SNCC staff member Don Jelinek later described this order as "the unsung heroes of the Selma March...who provided the only integrated Catholic church in Selma, and perhaps in the entire Deep South."

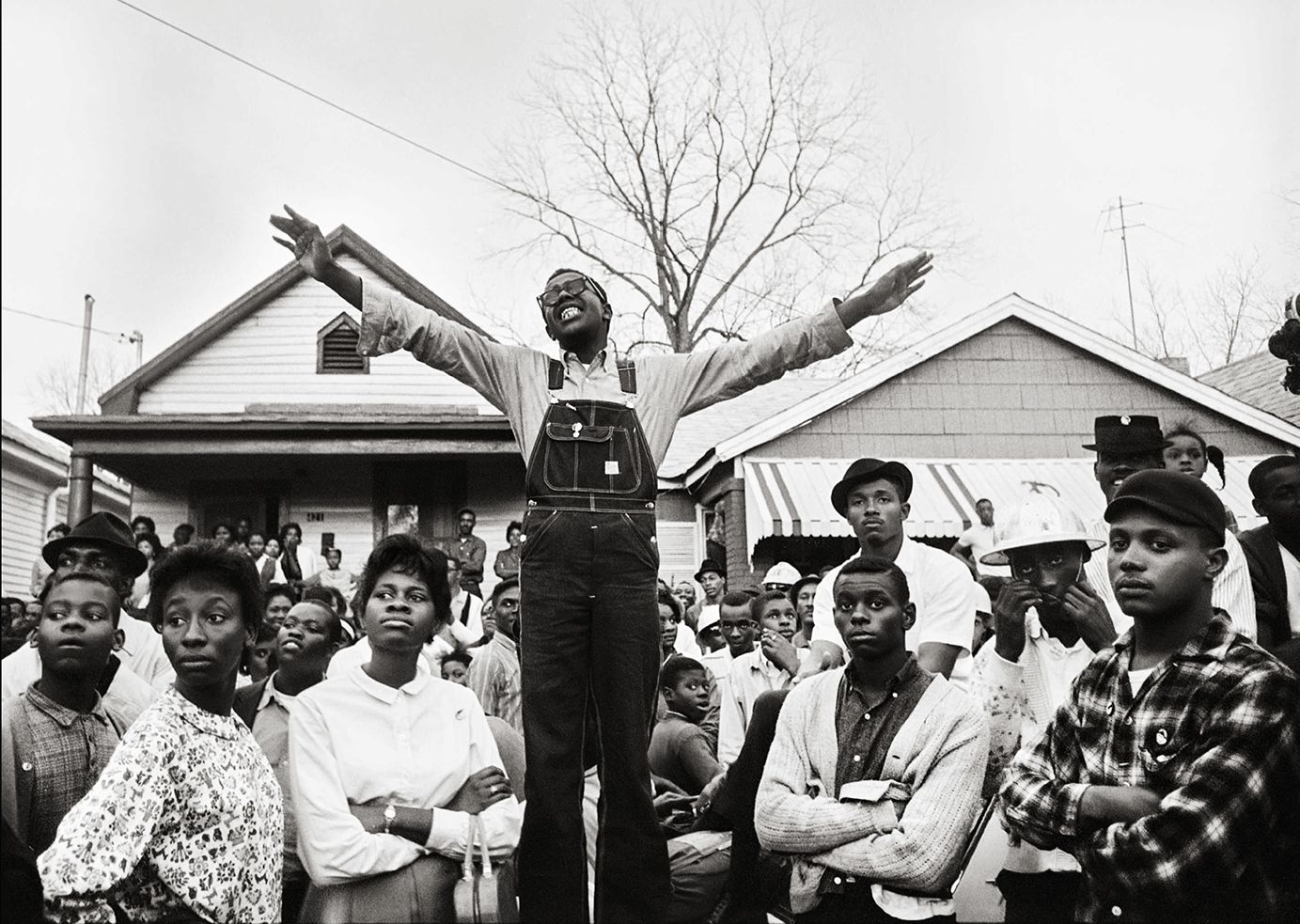

In early 1963, SNCC organizers Bernard Lafayette and Colia Liddel Lafayette arrived in Selma to begin a voter-registration project in cooperation with the DCVL. In mid-June, Bernard was beaten and almost killed by Klansmen determined to prevent black people from voting. When the Lafayettes returned to college in the fall, SNCC organizers Prathia Hall and Worth Long carried on the work despite arrests, beatings, and death threats. When 32 black schoolteachers applied at the county courthouse to register as voters, they were immediately fired by the all-white school board. After the Birmingham church bombing on September 15, 1963, which killed four black girls, black students in Selma began sit-ins at local lunch counters to protest segregation; they were physically attacked and arrested. More than 300 were arrested in two weeks of protests, including SNCC chairman John Lewis. On October 7, 1963, one of two days during the month when residents were allowed to go to the courthouse to apply to register to vote, SNCC's James Foreman and the DCVL mobilized more than 300 black people from Dallas County to line up at the voter registration office in what was called a "Freedom Day." Supporting them were national figures: author James Baldwin and his brother David, and comedian Dick Gregory and his wife Lillian (she was later arrested for picketing with SNCC activists and local supporters). SNCC members who tried to bring water to African Americans waiting in line were arrested, as were those who held signs saying, "Register to Vote." Ironically, a voter suppression law today in one state bans giving water to a voter in line in 2025. After waiting all day in the hot sun, only a handful of the hundreds in the line were allowed to fill out the voter application, and most of those applications were denied by white county officials. United States Justice Department lawyers and FBI agents were present and observing the scene but took no action against local officials.

On July 2, 1964, President Johnson signed the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, prohibiting segregation of public facilities. Some Jim Crow laws and customs remained in effect in Selma and other places for some time. When activists resumed efforts to integrate Selma's eating and entertainment venues, black people who tried to attend the Wilby Theatre or the Selmont Drive-in theater and eat at the 25¢ hamburger stand were both beaten and arrested. On July 6, 1964, one of the two registration days that month, John Lewis led 50 black citizens to the courthouse, but County Sheriff Jim Clark arrested them all instead of allowing them to apply to vote. On July 9, 1964, Judge James Hare issued an injunction forbidding any gathering of three or more people under the sponsorship of civil rights organizations or leaders. This injunction made it illegal for more than two people at a time to talk about civil rights or voter registration in Selma, suppressing public civil rights activity for the next six months. Then, 1965 existed. With civil rights activity blocked by Judge Hare's injunction, Frederick Douglas Reese requested the assistance of Dr. King and the SCLC. Reese was president of the DCVL, but the group declined to invite the SCLC; the invitation instead came from a group of local activists who would become known as the Courageous Eight – Ulysses S. Blackmon Sr., Amelia Boynton, Ernest Doyle, Marie Foster, James Gildersleeve, J.D. Hunter Sr., Henry Shannon Sr., and Reese.

Three of SCLC's main organizers – James Bevel, Diane Nash, and James Orange – had already been working on Bevel's Alabama Voting Rights Project since late 1963. King and the executive board of SCLC had not joined it. When SCLC officially accepted the invitation from the "Courageous Eight", Bevel, Nash, Orange, and others in SCLC began working in Selma in December 1964. They also worked in the surrounding counties, along with the SNCC staff who had been active there since early 1963.

Since the rejection of voting status for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegates by the regular delegates at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, major tensions between SCLC and SNCC had been brewing. SCLC ultimately remained neutral in the MFDP dispute to maintain its ties with the national Democratic coalition. Many SNCC members believed they were in an adversarial position with an American establishment which they thought had scorned grassroots democracy. SNCC's focus was on bottom-up organizing, establishing deep-rooted local power bases through community organizing. They had become distrustful of SCLC's spectacular mobilizations which were designed to appeal to the national media and Washington, DC, but which, most of SNCC believed, did not result in major improvements for the lives of African Americans on the ground. But, SNCC chairman John Lewis (also an SCLC board member), believed mass mobilizations to be invaluable, and he urged the group to participate. SNCC called in Fay Bellamy and Silas Norman to be full-time organizers in Selma.

By early 1965, the Selma movement had grown. Back then, the city of Selma had both moderate and hardline segregationists in its white capitalist power structure. The newly elected Mayor Joseph Smitherman was a moderate who hoped to attract Northern business investment, and he was very conscious of the city's image. Smitherman appointed veteran lawman Wilson Baker to head the city's 30-man police force. Baker believed that the most effective method of undermining civil rights protests was to de-escalate them and deny them publicity, as Police Chief Laurie Pritchett had done against the Albany Movement in Georgia. Activists knew that Baker was more sophisticated than other sheriffs.

The hardline of segregation was represented by the overtly racist Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark, who used violence and repression to maintain Jim Crow. He commanded a posse of 200 deputies, some of whom were members of Ku Klux Klan chapters or the National States' Rights Party. Posse men were armed with electric cattle-prods. Some were mounted on horseback and carried long leather whips they used to lash people on foot. Clark and Chief Baker were known to spar over jurisdiction. Baker's police patrolled the city except for the block of the county courthouse, which Clark and his deputies controlled. Outside the city limits, Clark and his volunteer posse were in complete control in the county.

The Selma Voting Rights Campaign in the modern sense started officially on January 2, 1965, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed a mass meeting in Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in defiance of the anti-meeting injunction. The date had been chosen because Sheriff Clark was out of town, and Chief Baker had stated he would not enforce the injunction. Over the following weeks, SCLC and SNCC activists expanded voter registration drives and protests in Selma and the adjacent Black Belt counties. By early January, there were preparations for mass registration. Dr. King went out of town to raise money via fundraising. So, Diane Nash led the charge to have the registration project. On January 15, 1965, Dr. King called President Johnson and the two agreed to start a major push for voting rights legislation, which would assist in advancing the passage of more anti-poverty legislation. After Dr. King returned to Selma, the first big "Freedom Day" of the new campaign occurred on January 18, 1965. According to their respective strategies, Chief Baker's police were cordial toward demonstrators, but Sheriff Clark refused to let black registrants enter the county courthouse. Clark made no arrests or assaults at this time. However, in an incident that drew national attention, Dr. King was knocked down and kicked by a leader of the National States Rights Party, who was quickly arrested by Chief Baker. Baker also arrested the head of the American Nazi Party, George Lincoln Rockwell, who said he'd come to Selma to "run King out of town." After the assault on Dr. King by the white supremacist in January 1965, black nationalist leader Malcolm X had sent an open telegram to George Lincoln Rockwell, stating: "if your present racist agitation against our people there in Alabama causes physical harm ... you and your KKK friends will be met with maximum physical retaliation from those of us who...believe in asserting our right to self-defense by any means necessary."

Over the next week, black people persisted in their attempts to register. Sheriff Clark responded by arresting organizers, including Amelia Boynton and Hosea Williams. Eventually, 225 registrants were arrested as well at the county courthouse. Their cases were handled by the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. On January 20, 1965, President Johnson gave his inaugural address but did not mention voting rights. Up to this point, the overwhelming majority of registrants and marchers were sharecroppers, blue-collar workers, and students. On January 22, Frederick Reese, a black schoolteacher who was also DCVL President, finally convinced his colleagues to join the campaign and register en masse. When they refused Sheriff Clark's orders to disperse at the courthouse, an ugly scene commenced. Clark's posse beat the teachers away from the door, but they rushed back only to be beaten again. The teachers retreated after three attempts and marched to a mass meeting where they were celebrated as heroes by the black community. On January 25, U.S. District Judge Daniel Thomas issued rules requiring that at least 100 people must be permitted to wait at the courthouse without being arrested. After Dr. King led marchers to the courthouse that morning, Jim Clark began to arrest all registrants in excess of 100, and corral the rest. Annie Lee Cooper, a fifty-three-year-old practical nurse who had been part of the Selma movement since 1963, struck Clark after he twisted her arm, and she knocked him to his knees as Cooper used self-defense. Four deputies seized Cooper, and photographers captured images of Clark beating her repeatedly with his club. The crowd was inflamed, and some wanted to intervene against Clark, but King ordered them back as Cooper was taken away. Although Cooper had violated nonviolent discipline, the movement rallied around her. Jim Clark and those officers were cowardly for assaulting a black woman desiring voting rights. James Bevel, speaking at a mass meeting, deplored her actions because "then [the press] don't talk about the registration." But when asked about the incident by Jet magazine, Bevel said, "Not everybody who registers is nonviolent; not everybody who registers is supposed to be nonviolent." The incident between Clark and Cooper was a media sensation, putting the campaign on the front page of The New York Times. When asked if she would do it again, Cooper told Jet, "I try to be nonviolent, but I just can't say I wouldn't do the same thing all over again if they treat me brutish like they did this time."

By February of 1965, more events happened. Dr. King wanted to get arrested to call attention to the voting rights issues in Selma. On February 1, King and Ralph Abernathy refused to cooperate with Chief Baker's traffic directions on the way to the courthouse, calculating that Baker would arrest them, putting them in the Selma city jail run by Baker's police, rather than the county jail run by Clark's deputies. Once processed, King and Abernathy refused to post bond. On the same day, SCLC and SNCC organizers took the campaign outside of Dallas County for the first time; in nearby Perry County, 700 students and adults, including James Orange, were arrested. On the same day, students from Tuskegee Institute, working in cooperation with SNCC, were arrested for acts of civil disobedience in solidarity with the Selma campaign. In New York and Chicago, Friends of SNCC chapters staged sit-ins at federal buildings in support of Selma black people, and CORE chapters in the North and West also mounted protests. Solidarity pickets began circling in front of the White House late into the night.

Fay Bellamy and Silas Norman attended a talk by Malcolm X to 3,000 students at the Tuskegee Institute and invited him to address a mass meeting at Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church to kick off the protests on the morning of February 4, 1965. When Malcolm X arrived, SCLC staff initially wanted to block his talk, but he assured them that he did not intend to undermine their work. During his address, Malcolm X warned the protesters about "House Negroes" who, he said, were a hindrance to black liberation. Dr. King later said that he thought this was an attack on him. But Malcolm told Coretta Scott King that he thought to aid the campaign by warning white people what "the alternative" would be if Dr. King failed in Alabama. Bellamy recalled that Malcolm told her he would begin recruiting in Alabama for his Organization of Afro-American Unity later that month (Malcolm was assassinated two weeks later).

On February 4, President Lyndon Johnson made his first public statement in support of the Selma campaign. At midday, Judge Thomas, at the Justice Department's urging, issued an injunction that suspended Alabama's current literacy test, ordered Selma to take at least 100 applications per registration day, and guaranteed that all applications received by June 1 would be processed before July. In response to Thomas' favorable ruling, and in alarm at Malcolm X's visit, Andrew Young, who was not in charge of the Selma movement, said he would suspend demonstrations. James Bevel, however, continued to ask people to line up at the voter's registration office as they had been doing, and Dr. King called Young from jail, telling him the demonstrations would continue. They did so the next day, and more than 500 protesters were arrested.

On February 5, King bailed himself and Abernathy out of jail. On February 6, the White House announced that it would urge Congress to enact a voting rights bill during the current session and that the vice-president and Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach would meet with King in the following week. On February 9, King met with Attorney General Katzenbach, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, and White House aides before having a brief, seven-minute session with President Johnson. Following the Oval Office visit, King reported that Johnson planned to deliver his message "very soon." Throughout that February, King, SCLC staff, and members of Congress met for strategy sessions at the Selma, Alabama home of Richie Jean Jackson. In addition to actions in Selma, marches and other protests in support of voting rights were held in neighboring Perry, Wilcox, Marengo, Greene, and Hale counties. Attempts were made to organize in Lowndes County, but fear of the Klan there was so intense from previous violence and murders that black people would not support a nonviolent campaign in great number, even after Dr. King made a personal appearance on March 1.

Overall, more than 3,000 people were arrested in protests between January 1 and February 7, but black people achieved fewer than 100 new registered voters. In addition, hundreds of people were injured or blacklisted by employers due to their participation in the campaign. DCLV activists became increasingly wary of SCLC's protests, preferring to wait and see if Judge Thomas' ruling of February 4 would make a long-term difference. SCLC was less concerned with Dallas County's immediate registration figures, and primarily focused on creating a public crisis that would make a voting rights bill the White House's number one priority. James Bevel and C. T. Vivian both led dramatic nonviolent confrontations at the courthouse in the second week of February. Selma students organized themselves after the SCLC leaders were arrested. King told his staff on February 10 that "to get the bill passed, we need to make a dramatic appeal through Lowndes and other counties because the people of Selma are tired." By the end of the month, 300 black human beings were registered in Selma, compared to 9500 whites.

By the end of February, activists planned for the first Selma to Montgomery march. On February 18, 1965, C. T. Vivian led a march to the courthouse in Marion, the county seat of neighboring Perry County, to protest the arrest of James Orange. State officials had received orders to target Vivian, and a line of Alabama state troopers waited for the marchers at the Perry County courthouse. Officials had turned off all of the nearby streetlights, and state troopers rushed at the protesters, attacking them. Protesters Jimmie Lee Jackson, his grandfather and his mother fled the scene to hide in a nearby café. Alabama State Trooper corporal James Bonard Fowler followed Jackson into the café and shot him, saying he thought the protester was trying to get his gun as they grappled. Jackson died eight days later at Selma's Good Samaritan Hospital of an infection resulting from the gunshot wound. The death of Jimmie Lee Jackson prompted civil rights leaders to bring their cause directly to Alabama Governor George Wallace by performing a 54 mi (87 km) march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery. Jackson was the only male wage-earner of his household, which lived in extreme poverty. Jackson's grandfather, mother, wife, and children were left with no source of income. The truth is that Jimmie Lee Jackson was trying to protect the life of his mother, Viola Jackson, in a cafe, and the police shot him twice in the abdomen for no reason. Jackson was beaten by the police after he was shot and collapsed in front of the bus station. He died in the hospital. The cowardly police officers also beat an 82-year-old grandfather of Jackson, Cager Lee in the Mack's Cafe too.

Bloody Sunday

During a public meeting at Zion United Methodist Church in Marion on February 28, after Jackson's death, emotions were running high. James Bevel, as director of the Selma voting rights movement for SCLC, called for a march from Selma to Montgomery to talk to Governor George Wallace directly about Jackson's death, and to ask him if he had ordered the State Troopers to turn off the lights and attack the marchers. Bevel strategized that this would focus the anger and pain of the people of Marion and Selma toward a nonviolent goal, as many were so outraged that they wanted to retaliate with violence. The marchers wanted to bring attention to the many violations of black people's constitutional rights by marching to Montgomery. Dr. King agreed with Bevel's plan of the march, which they both intended to symbolize a march for full voting rights. They were to ask Governor Wallace to protect black registrants. SNCC had severe reservations about the march, especially when they heard that King would not be present. They permitted John Lewis to participate, and SNCC provided logistical support, such as the use of its Wide Area Telephone Service (WATS) lines and the services of the Medical Committee on Human Rights, organized by SNCC during the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964. Governor Wallace denounced the march as a threat to public safety; he said that he would take all measures necessary to prevent it from happening. "There will be no march between Selma and Montgomery," Wallace said on March 6, 1965, citing concern over traffic violations. He ordered Alabama Highway Patrol Chief Col. Al Lingo to "use whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march."

Bloody Sunday existed on March 7, 1965. On that day, an estimated 525 to 600 civil rights marchers headed southeast out of Selma on U.S. Highway 80. The march was led by John Lewis of SNCC and the Reverend Hosea Williams of SCLC, followed by Bob Mants of SNCC and Albert Turner of SCLC. The protest went according to plan until the marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, where they saw a wall of state troopers and county posse waiting for them on the other side. County sheriff Jim Clark had issued an order for all white men in Dallas County over the age of twenty-one to report to the courthouse that morning to be deputized. Commanding officer John Cloud told the demonstrators to disband at once and go home. Rev. Hosea Williams tried to speak to the officer, but Cloud curtly informed him there was nothing to discuss. Seconds later, the troopers began shoving the demonstrators, knocking many to the ground and beating them with nightsticks. Another detachment of troopers fired tear gas, and mounted troopers charged the crowd on horseback. Televised images of the brutal attack presented Americans and international audiences with horrifying images of marchers left bloodied and severely injured, and roused support for the Selma Voting Rights Campaign. Amelia Boynton, who had helped organize the march as well as marching in it, was beaten unconscious. A photograph of her lying on the road of the Edmund Pettus Bridge appeared on the front page of newspapers and news magazines around the world. Another marcher, Lynda Blackmon Lowery, age 14, was brutally beaten by a police officer during the march and needed seven stitches for a cut above her right eye and 28 stitches on the back of her head. John Lewis suffered a skull fracture and bore scars on his head from the incident for the rest of his life. In all, 17 marchers were hospitalized and 50 treated for lesser injuries; the day soon became known as "Bloody Sunday."

After the march, President Johnson issued an immediate statement "deploring the brutality with which a number of Negro citizens of Alabama were treated." He also promised to send a voting rights bill to Congress that week, although it took him until March 15. SNCC officially joined the Selma campaign, putting aside their qualms about SCLC's tactics to rally for "the fundamental right of protest." SNCC members independently organized sit-ins in Washington, DC, the following day, occupying the office of Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach until they were dragged away.

The executive board of the NAACP unanimously passed a resolution the day after "Bloody Sunday", warning, "If Federal troops are not made available to protect the rights of Negroes, then the American people are faced with terrible alternatives. Like the citizens of Nazi-occupied France, Negroes must either submit to the heels of their oppressors or they must organize underground to protect themselves from the oppression of Governor Wallace and his storm troopers." In response to "Bloody Sunday", labor leader Walter Reuther sent a telegram on March 9 to President Johnson, reading in part: "Americans of all religious faiths, of all political persuasions, and from every section of our Nation are deeply shocked and outraged at the tragic events in Selma Ala., and they look to the Federal Government as the only possible source to protect and guarantee the exercise of constitutional rights, which is being denied and destroyed by the Dallas County law enforcement agents and the Alabama State troops under the direction of Governor George Wallace. Under these circumstances, Mr. President, I join in urging you to take immediate and appropriate steps including the use of Federal marshals and troops if necessary, so that the full exercise of constitutional rights including free assembly and free speech be fully protected." After Bloody Sunday, the Selma Voting Rights Movement entered a new and final phase.

Turnaround Tuesday

Dr. King, Nash, Bevel, and other people organized a second march to be held on Tuesday, March 9, 1965. They wanted clergy and citizens from across the nation to join them. Hundreds of people joined the call from the SCLC as they were outraged at television images of Bloody Sunday. The Civil Rights Movement grown in more influence. To prevent another outbreak of violence, SCLC attempted to gain a court order that would prohibit the police from interfering. Instead of issuing the court order, U.S. District Court Judge Frank Minis Johnson issued a restraining order, prohibiting the march from taking place until he could hold additional hearings later in the week. Based on past experience, some in the SCLC were confident that Judge Johnson would eventually lift the restraining order. They didn't want to alienate one of the few southern judges who had displayed sympathy to their cause by violating the injunction. The SCLC didn't have a large infrastructure in place to support the long march, one for which the marchers were equipped. They knew that violating a court order could result in punishment for contempt, even if the order is later reversed.

Some people in Selma movement, both local and from across the country, wanted to march on Tuesday to protest both the "Bloody Sunday" violence and the systematic denial of black voting rights in Alabama. Both Hosea Williams and James Forman argued that the march must proceed and by the early morning of the march date, and after much debate, Dr. King had decided to lead people to Montgomery. Assistant Attorney General John Doar and former Florida governor LeRoy Collins, representing President Lyndon Johnson, went to Selma to meet with King and others at Richie Jean Jackson's house and privately urged King to postpone the march. The SCLC president told them that his conscience demanded that he proceed, and that many movement supporters, especially in SNCC, would go ahead with the march even if he told them it should be called off. Collins suggested to King that he make a symbolic witness at the bridge, then turn around and lead the marchers back to Selma. King told them that he would try to enact the plan provided that Collins could ensure that law enforcement would not attack them. Collins obtained this guarantee from Sheriff Clark and Al Lingo in exchange for a guarantee that King would follow a precise route drawn up by Clark. On the morning of March 9, 1965, this day would be known as Turnaround Tuesday. Collins handed Dr. King the secretly agreed route. King led about 2,500 marchers out on the Edmund Pettus Bridge and held a short prayer session before turning them around, thereby obeying the court order preventing them from making the full march, and following the agreement made by Collins, Lingo, and Clark. He did not venture across the border into the unincorporated area of the county, even though the police unexpectedly stood aside to let them enter. This plan angered many protesters as this plan was created in secret without input from SNCC.

As only SCLC leaders had been told in advance of the plan, many marchers felt confusion and consternation, including those who had traveled long distances to participate and oppose police brutality. King asked them to remain in Selma for another march to take place after the injunction was lifted. That evening, three white Unitarian Universalist ministers in Selma for the march were attacked on the street and beaten with clubs by four KKK members. The worst injured was Reverend James Reeb from Boston. Fearing that Selma's public hospital would refuse to treat Reeb, activists took him to Birmingham's University Hospital, two hours away. Reeb died on Thursday, March 11 at University Hospital, with his wife by his side. Many people mourned the death of Rev. James Reeb. Tens of thousands held vigils in his honor. President Johnson called Reeb's widow and father to express his condolences (he would later invoke Reeb's memory when he delivered a draft of the Voting Rights Act to Congress). Black people in Dallas County and the Black Belt mourned the death of Reeb, as they had earlier mourned the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson. But many activists were bitter that the media and national political leaders expressed great concern over the murder of Reeb, a northern white man in Selma, but had paid scant attention to that of Jackson, a local African American. SNCC organizer Kwame Ture argued that "the movement itself is playing into the hands of racism, because what you want as a nation is to be upset when anybody is killed [but] for it to be recognized, a white person must be killed. Well, what are you saying?" What Kwame Ture meant is that a black life is as valuable as any other life of any other color.

Dr. King's credibility in the movement was shaken by the secret turnaround agreement. David Garrow notes that King publicly "waffled and dissembled" on how his final decision had been made. On some occasions King would inaccurately claim that "no pre-arranged agreement existed", but under oath before Judge Johnson, he acknowledged that there had been a "tacit agreement." Criticism of King by radicals in the movement became increasingly pronounced, with James Forman calling Turnaround Tuesday, "a classic example of trickery against the people." Following the death of James Reeb, a memorial service was held at the Brown's Chapel AME Church on March 15, 1965. Among those who addressed the packed congregation were Dr. King, labor leader Walter Reuther, and some clergymen. A picture of King, Reuther, Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos and others in Selma for Reeb's memorial service appeared on the cover of Life magazine on March 26, 1965. After the memorial service, upon getting permission from the courts, the leaders and attendees marched from the Brown's Chapel AME Church to the Dallas County Courthouse in Selma.

The Selma to Montgomery March

More events in Montgomery, Alabama took place. After the turnaround in the second march, the Selma movement organizing were waiting for a judicial order to safely proceed. Tuskegee Institute students, led by Gwen Patton and Sammy Younge Jr. decided to open a Second Front by marching to the Alabama State Capitol and delivering a petition to Governor Wallace. They were joined quickly by James Forman and much of the SNCC staff from Selma. The SNCC members in many cases had a distrust of Dr. King after the turnaround Tuesday and wanted to have a separate course. By March 11, 1965, SNCC started many demonstrations in Montgomery and put out a national call for others to join them. James Bevel was SCLC's Selma leader followed them and discouraged their activities. This caused conflict between SCLC and Forman plus the SNCC. Bevel accused Forman of trying to divert people from the Selma campaign and of abandoning nonviolent discipline. Forman accused Bevel of driving a wedge between the student movement and the local black churches. The argument was resolved only when both were arrested.

On March 11, 1965, seven Selma solidarity activists sat in at the East Wing of the White House until they were arrested. Dozens of other protesters also tried to occupy the White House that weekend but were stopped by guards; they blocked Pennsylvania Avenue instead. On March 12, President Johnson had an unusually belligerent meeting with a group of civil rights advocates including Bishop Paul Moore, Reverend Robert Spike, and SNCC representative H. Rap Brown. Johnson complained that the White House protests were disturbing his family. The activists were unsympathetic and demanded to know why he hadn't delivered the voting rights bill to Congress yet, or sent federal troops to Alabama to protect the protesters. In this same period, SNCC, CORE, and other groups continued to organize protests in more than eighty cities, actions that included 400 people blocking the entrances and exits of the Los Angeles Federal Building. President Johnson told the press that he refused to be "blackjacked" into action by unruly "pressure groups." The truth is pressure from activist group using protests and civil disobedience are legitimate tactics in getting solutions enacted. The next day he arranged a personal meeting with Governor Wallace, urging him to use the Alabama National Guard to protect marchers. He also began preparing the final draft of his voting rights bill. On March 11, Attorney General Katzenbach announced that the federal government was intending to prosecute local and state officials who were responsible for the attacks on the marchers on March 7. He would use an 1870 civil rights law as the basis for charges.

On March 15, 1965, the president convened a joint session of Congress, outlined his new voting rights bill, and demanded that they pass it. In a historic presentation carried nationally on live television, making use of the largest media network, Johnson praised the courage of African-American activists. He called Selma "a turning point in man's unending search for freedom" on a par with the Battle of Appomattox in the American Civil War. Johnson added that his entire Great Society program, not only the voting rights bill, was part of the Civil Rights Movement. He adopted language associated with Dr. King, declaring that "it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome." Afterward, King sent a telegram to Johnson congratulating him for his speech, calling it "the most moving eloquent unequivocal and passionate plea for human rights ever made by any president of this nation." Johnson's voting rights bill was formally introduced in Congress two days later.

On March 15-16, 1965, SNCC led several hundred demonstrations (that included Alabama students, Northern students, and local adults) in protests near the capitol complex. The Montgomery County sheriff's posse met them on horseback and drove them back, whipping them. Against the objections of James Bevel, some protesters threw bricks and bottles at police. At a mass meeting on the night of the 16th, Forman "whipped the crowd into a frenzy" demanding that the President act to protect demonstrators, and warned, "If we can't sit at the table of democracy, we'll knock the f____ legs off." The New York Times featured the Montgomery confrontations on the front page the next day. Although King was concerned by Forman's rhetoric, he joined him in leading a march of 2000 people in Montgomery to the Montgomery County courthouse. According to historian Gary May, "City officials, also worried by the violent turn of events ... apologized for the assault on SNCC protesters and invited King and Forman to discuss how to handle future protests in the city." In the negotiations, Montgomery officials agreed to stop using the county posse against protesters, and to issue march permits to black people for the first time.

The third and successful March from Selma to Montgomery was the product of many things. On March 17, 1965 (a week after Rev. James Reeb's death on Wednesday), Judge Johnson ruled in favor of the protesters. He said that their First Amendment right to march in protest could not be abridged by the state of Alabama in the following words: "The law is clear that the right to petition one's government for the redress of grievances may be exercised in large groups...These rights may...be exercised by marching, even along public highways." Judge Johnson had sympathized with the protesters for many days but had withheld his order until he received a total commitment of enforcement from the White House. President Johnson had avoided such a commitment in sensitivity to the power of the state's rights movement and attempted to cajole Governor Wallace into protecting the marchers himself, or at least giving the president permission to send troops. Finally, seeing that Wallace had no intention of doing either, the president gave his commitment to Judge Johnson on the morning of March 17, and the judge issued his order the same day. To ensure that this march would not be as unsuccessful as the first two marches were, the president federalized the Alabama National Guard on March 20 to escort the marchers from Selma. The ground operation was supervised by Deputy U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark. He also sent Joseph A. Califano Jr., who at the time served as Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense, to outline the progress of the march. In a series of letters, Califano reported on the march at regular intervals for the four days.

On Sunday, March 21, 1965, almost 8,000 people assembled at Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church to start the journey to Montgomery. Most of the participants were black Americans. Also, there were many white Americans, Asian Americans, and Latino Americans who were involved in the Selma to Montgomery final march too. Spiritual leaders of multiple races, religions, and creeds marched abreast with Dr. King, including Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Greek Orthodox Archbishop Iakovos, Rabbis Abraham Joshua Heschel and Maurice Davis, and at least one nun, all of whom were depicted in a photo that has become famous. The Dutch Catholic priest Henri Nouwen joined the march on March 24. In 1965, the road to Montgomery was four lanes wide going east from Selma, then narrowed to two lanes through Lowndes County, and widened to four lanes again at the Montgomery County border. Under the terms of Judge Johnson's order, the march was limited to no more than 300 participants for the two days they were on the two-lane portion of US 80. At the end of the first day, most of the marchers returned to Selma by bus and car, leaving 300 to camp overnight and take up the journey the next day. On March 22 and 23, 300 protesters marched through chilling rain across Lowndes County, camping at three sites in muddy fields. At the time of the march, the population of Lowndes County was 81% black and 19% white, but not a single black person was registered to vote. There were 2,240 whites registered to vote in Lowndes County, a figure that represented 118% of the adult white population (in many Southern counties of that era it was common practice to retain white voters on the rolls after they died or moved away). On March 23, hundreds of black marchers wore kippot, Jewish skullcaps, to emulate the marching rabbis, as Heschel was marching at the front of the crowd. The marchers called the kippot "freedom caps."

On the morning of March 24, 1965, the march went to Montgomery County, and the highway widened again to four lanes. All Day, as the marchers approached the city, additional marchers were ferried by bus and car to join the line. By evening, several thousand marchers had reached the final campsite at the City of St. Jude, a complex on the outskirts of Montgomery. That night on a makeshift stage, a "Stars for Freedom" rally was held, with singers Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett, Frankie Laine, Peter, Paul and Mary, Sammy Davis Jr., Joan Baez, Nina Simone, and The Chad Mitchell Trio all performing. Thousands more people continued to join the march.

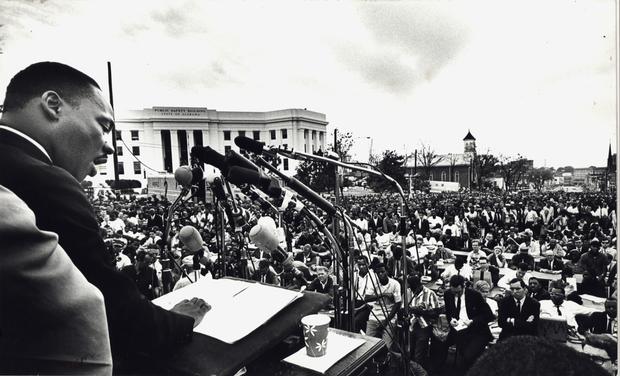

Martin Luther King, Jr. delivers his “How Long, Not Long” speech on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, Alabama, March 25, 1965. (Spider Martin/Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery).

On Thursday, March 25, 25,000 people marched from St. Jude to the steps of the State Capitol Building where King delivered the speech "How Long, Not Long". He said:

"...The end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience...The only normalcy that we will settle for (Yes, sir) is the normalcy that recognizes the dignity and worth of all of God’s children. The only normalcy that we will settle for is the normalcy that allows judgment to run down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream. (Yes, sir) The only normalcy that we will settle for is the normalcy of brotherhood, the normalcy of true peace, the normalcy of justice...I come to say to you this afternoon, however difficult the moment, (Yes, sir) however frustrating the hour, it will not be long, (No sir) because “truth crushed to earth will rise again.” (Yes, sir)

How long? Not long, (Yes, sir) because “no lie can live forever.” (Yes, sir)

How long? Not long, (All right. How long) because “you shall reap what you sow.” (Yes, sir)

How long? (How long?) Not long: (Not long)

Truth forever on the scaffold, (Speak)

Wrong forever on the throne, (Yes, sir)

Yet that scaffold sways the future, (Yes, sir)

And, behind the dim unknown,

Standeth God within the shadow,

Keeping watch above his own.

How long? Not long, because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. (Yes, sir)

How long? Not long, (Not long) because:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord; (Yes, sir)

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored; (Yes)

He has loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword; (Yes, sir)

His truth is marching on. (Yes, sir)

He has sounded forth the trumpet that shall never call retreat; (Speak, sir)

He is sifting out the hearts of men before His judgment seat. (That’s right)

O, be swift, my soul, to answer Him! Be jubilant my feet!

Our God is marching on. (Yeah)

Glory, hallelujah! (Yes, sir) Glory, hallelujah! (All right)

Glory, hallelujah! Glory, hallelujah!

His truth is marching on. [Applause]..."

After delivering the speech, Dr. King and the marchers approached the entrance to the Capitol with a petition for Governor Wallace. A line of state troopers blocked the door. One announced that the governor was not in. Undeterred, the marchers remained at the entrance until one of Wallace's secretaries appeared and took the petition.

Later that night, Viola Liuzzo, a white mother of five from Detroit who had come to Alabama to support voting rights for black human beings, was assassinated by Ku Klux Klan members while she was ferrying marchers back to Selma from Montgomery. Among the Klansmen in the car from which the shots were fired was FBI informant Gary Rowe. Afterward, the FBI's COINTELPRO operation spread false rumors that Liuzzo was a member of the Communist Party and had abandoned her children to have sexual relationships with African-American activists. The FBI lied once again, and J. Edgar Hoover was a coward to allow his agents to slander an innocent woman, who was Liuzzo. Murder is always wrong. The third Selma march received national and international coverage. The Selma march showed the courage of the people who desired voting rights and justice for all. Racists like U.S. Representative William Louis Dickinson accused the marchers of alcohol abuse, bribery, being part of a Communist conspiracy to destabilize America, and other sexual acts, but people of all ages were in the march. These allegations were false and denied by local and national journalists plus religious leaders (Congressmen William Fitts Ryand and Joseph Yale Resnick denied the allegations from Dickinson. Dickson opposed the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the 1968 Civil Rights Act). The truth is that American citizens of every color and background have the right to vote and other human rights without discrimination and without oppression, period.

There was the unsung event of the Hammermill boycott. During 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. was promoting an economic boycott of Alabama products to put pressure on the State to integrate schools and employment. In an action under development for some time, the Hammermill Paper Company announced the opening of a major plant in Selma, Alabama; this came during the height of violence in early 1965. On February 4, 1965, the company announced plans for the construction of a $35 million plant, allegedly touting the "fine reports the company had received about the character of the community and its people." On March 26, 1965, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee called for a national boycott of Hammermill paper products until the company reversed what SNCC described as racist policies. The SCLC joined in support of the boycott. In cooperation with SCLC, student members of Oberlin College Action for Civil Rights joined with SCLC members to conduct picketing and a sit-in at Hammermill's Erie, Pennsylvania headquarters. White activist and preacher Robert W. Spike called Hammermill's decision as "an affront not only to 20 million American Negroes, but also to all citizens of goodwill in this country." He also criticized Hammermill executives directly, stating: "For the board chairman of one of America's largest paper manufacturers to sit side by side with Governor Wallace of Alabama and say that Selma is fine ... is either the height of naiveté or the depth of racism."

The company called a meeting of the corporate leadership, SCLC's C. T. Vivian, and Oberlin student leadership. Their discussions led to Hammermill executives signing an agreement to support integration in Alabama. The agreement also required Hammermill to commit to equal pay for black and white workers. During these negotiations, around 50 police officers arrived outside the Erie headquarters and arrested 65 activists, charging them with obstruction of an officer. Before the march to Montgomery concluded, SNCC staffers Kwame Ture and Cleveland Sellers committed themselves to registering voters in Lowndes County for the next year. Their efforts resulted in the creation of the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, an independent third party.

The Voting Rights Act Signed

After long debate, the voting rights bill was passed during the summer and signed by President Lyndon Baines Johnson as the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965. Many people in the Civil Rights Movement celebrated the bill being signed into law. The bill was signed by President Johnson in an August 6 ceremony attended by Amelia Boynton and many other civil rights leaders and activists. This act prohibited most of the unfair practices used to prevent black people from registering to vote and provided for federal registrars to go to Alabama and other states with a history of voting-related discrimination to ensure that the law was implemented by overseeing registration and elections.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movement on August 6, 1965, and Congress later amended the Act five times to expand its protections. Designed to enforce the voting rights protected by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, the Act sought to secure the right to vote for racial minorities throughout the country, especially in the South. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the Act is considered to be the most effective piece of federal civil rights legislation ever enacted in the country. The National Archives and Records Administration stated: "The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was the most significant statutory change in the relationship between the federal and state governments in the area of voting since the Reconstruction period following the Civil War." The act contains numerous provisions that regulate elections. The act's "general provisions" provide nationwide protections for voting rights. Section 2 is a general provision that prohibits state and local governments from imposing any voting rule that "results in the denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen to vote on account of race or color" or membership in a language minority group. Other general provisions specifically outlaw literacy tests and similar devices that were historically used to disenfranchise racial minorities. The act also contains "special provisions" that apply only to certain jurisdictions. A core special provision is the Section 5 preclearance requirement, which prohibited certain jurisdictions from implementing any change affecting voting without first receiving confirmation from the U.S. attorney general or the U.S. District Court for D.C. that the change does not discriminate against protected minorities. Another special provision requires jurisdictions containing significant language minority populations to provide bilingual ballots and other election materials.

Section 5 and most other special provisions applied to jurisdictions encompassed by the "coverage formula" prescribed in Section 4(b). The coverage formula was originally designed to encompass jurisdictions that engaged in egregious voting discrimination in 1965, and Congress updated the formula in 1970 and 1975. In Shelby County v. Holder (2013), the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the coverage formula as unconstitutional, reasoning that it was obsolete. The court did not strike down Section 5, but without a coverage formula, Section 5 is unenforceable. The jurisdictions which had previously been covered by the coverage formula massively increased the rate of voter registration purges after the Shelby decision. In 2021, the Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee Supreme Court ruling reinterpreted Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, substantially weakening it. The ruling interpreted the "totality of circumstances" language of Section 2 to mean that it does not generally prohibit voting rules that have a disparate impact on the groups that it sought to protect, including a rule blocked under Section 5 before the Court inactivated that section in Shelby County v. Holder. In particular, the ruling held that fears of election fraud could justify such rules without evidence that any such fraud had occurred in the past or that the new rule would make elections safer.

Research shows that the Act had successfully and massively increased voter turnout and voter registrations, in particular among black people. The Act has also been linked to concrete outcomes, such as greater public goods provision (such as public education) for areas with higher black population shares, more members of Congress who vote for civil rights-related legislation, and greater Black representation in local offices. The Supreme Court's Selby decision and the 2021 decision are wrong in my opinion. The Voting Rights Act should be strengthened, not weakened. Voting is a human right along with due process. In the early years of the Act, overall progress was slow, with local registrars continuing to use their power to deny African Americans voting access. In most Alabama counties, for example, registration continued to be limited to two days per month. The United States Civil Rights Commission acknowledged that "The Attorney General moved slowly in exercising his authority to designate counties for examiners ... he acted only in counties where he had ample evidence to support the belief that there would be intentional and flagrant violation of the Act." Dr. King demanded that federal registrars be sent to every county covered by the Act, but Attorney General Katzenbach refused. By the summer of 1965, SCLC worked with SNCC and CORE to promote a large on the ground voter registration programs in the South. The Civil Rights Commission described this as a major contribution to expanding black voters in 1965, and the Justice Department acknowledged leaning on the work of "local organizations" in the movement to implement the Act. SCLC and SNCC were temporarily able to mend past differences through collaboration in the Summer Community Organization and Political Education project. Ultimately, their coalition foundered on SCLC's commitment to nonviolence and (at the time) the Democratic Party. Many activists worried that President Johnson still sought to appease Southern whites, and some historians support this view.

By March 1966, nearly 11,000 black people had registered to vote in Selma, where 12,000 whites were registered. More black people would register by November, when their goal was to replace County Sheriff Jim Clark; his opponent was Wilson Baker, for whom they had respect. In addition, five black people ran for office in Dallas County. Rev. P. H. Lewis, pastor of Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church, ran for state representative on the Democratic ticket. David Ellwanger, a brother of Rev. Joseph Ellwanger of Birmingham, who led supporters in Selma in 1965, challenged incumbent state senator Walter C. Givhan (d. 1976), a fierce segregationist and a power in the state senate. First elected to the state senate in 1954, Givhan retained his seat for six terms, even after redistricting that preceded the 1966 election. In November 1966, Katzenbach told Johnson regarding Alabama, that "I am attempting to do the least I can do safely without upsetting the civil rights groups." Katzenbach did concentrate examiners and observers in Selma for the "high-visibility" election between incumbent County Sheriff Jim Clark and Wilson Baker, who had earned the grudging respect of many local residents and activists. With 11,000 black people added to the voting rolls in Selma by March 1966, they voted for Baker in 1966, turning Clark out of office. Clark later was prosecuted and convicted of drug smuggling and served a prison sentence. The US Civil Rights Commission said that the murders of activists, such as Jonathan Daniels in 1965, had been a major impediment to voter registration.

Overall, the Justice Department assigned registrars to six of Alabama's 24 Black Belt counties during the late 1960s, and to fewer than one-fifth of all the Southern counties covered by the Act. Expansion of enforcement grew gradually, and the jurisdiction of the Act was expanded through a series of amendments beginning in 1970. An important change was made in 1972, when Congress passed an amendment that discrimination could be determined by "effect" rather than by trying to prove "intent." Thus, if county or local practices resulted in a significant minority population being unable to elect candidates of their choice, the practices were considered to be discriminatory in effect. In 1960, there were a total of 53,336 black voters registered in the state of Alabama; three decades later, there were 537,285, a tenfold increase.

What to do Next?

The sixtieth-year anniversary of the successful Selma voting rights movement and the 1965 Voting Rights Act ought to make us have a lot of appreciation of the sacrifice of heroes who stood up for our freedom like Sheyann Webb and Rachel West (who were little children back in 1965), Amelia Boynton, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Hosea Williams, Diane Nash, Kwame Ture, and other human beings. The black masses of human beings worked courageously in the movement. The organizations of DCVL, SCLC, and SNCC were crucial in the Selma movement for real social change. The Selma Voting Rights movement was also multiethnic, filled with people of every color back then who wanted to see the black people of Selma and nationwide in America to have equality, justice, and liberty. Back then, the American ruling class knew full well that it was greatly hypocritical to proclaim themselves as the arbitrators of "democracy," but see segregation in America and imperialism overseas (with the U.S. government's conduct in the imperialistic actions in Vietnam, the Dominican Republic, Greece, Congo, etc.). So, the progressive, freedom-loving people in America worked with diligence to allow the Voting Rights Act to be passed. 1965 was a transition year in world history. By this time, the postwar economic boom started to unravel. This era saw West Germany and Japan compete with America and Western Europe for resources. Automation was a reality, causing industrial jobs to decline involving manufacturing and other type of jobs. Also, the Vietnam War by the late 1960s not only stripped away resources for anti-poverty measures, but the war increased inflation, causing stagflation. In 1965, the Civil Rights Movement debated on what to do next. Some civil rights leaders wanted to continue in voting rights activism in the South, some wanted to go into the anti-war movement, some wanted to build a coalition in the Democratic Party to form an alliance to gain economic and political reforms, and some wanted to go into addressing the massive economic inequality in America.

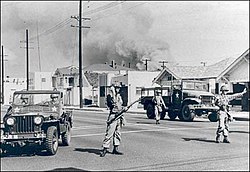

Immediately after the Voting Rights Act was signed, the Watts rebellion happened in Los Angeles, California. The events of Watts inspired Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to go into the next phase of the movement. That phase dealt with economic issues and social issues. As Dr. King said, it's fine to have civil rights, but that means little if a person doesn't have bread to eat or having a living wage to survive in the complexities of modern-day society. A lot of us black people from the South back then didn't realize the suffering and the hurt of the black people in the North, Midwest, and the West Coast (by 1965, many of those regions had civil rights legislation but they still had de facto segregation, which was segregation by unwritten rules, not literal laws). The rebellion in Watts took place in August 1965. It came after a dispute between a black family and the police. Black residents in Los Angeles were sick and tired of discrimination, economic oppression, racism, and other injustices inflicted on them like being treated as a colony under occupation. The Watts rebellion was so large that President Lyndon Baines Johnson called the California National Guard in Watts to stop it. There was the occupation by the police and the National Guard. The events resulted in 36 people died, about 1,000 people injured, 4,000 people arrested, and $200 million in buildings and other property being destroyed. More than 15,000 troops and 1,000 people were mobilized. Almost a 50 square mile area, the rebellion happened. The Watts rebellion was a product of massive racism, police brutality, and economic deprivation. Watts had more than 100,000 people lived in a small, crammed area. There were many people living in run down housing projects, and black families faced housing discrimination. Back then, the unemployment rate in Watts was 30 percent and half of the population was on welfare. These conditions were in the height of the postwar boom. Times were changing, and more institutions (including economic and political power) and other solutions had to be established to make society truly egalitarian. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to Watts to try to calm people down and promote nonviolence, but he was booed by many black residents in Watts. That was taboo as Dr. King was rarely booed by black people back then. Dr. King later realized that people booed not at him personally per se but at the system that deprived them of basic human rights and the chance to achieve their own dreams in the midst of the richest nation in human history. They were desperate for a social change. Therefore, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. changed to see that a radical redistribution of economic and political power was necessary in order to give black people true liberation.

In other words, it's fine to dismantle segregation. Back in the day, our ancestors fought Jim Crow not to bow down to white people or make ourselves extinct. We wanted desegregation, so we can control the resources in our community and have self-determination without legalized oppression. Malcolm X, Black Power advocates, and even Dr. King advocated black self-determination in developing our own institutions plus political and economic power. The problem with Jim Crow is that it was a system that the government controlled that forced black people to have lax rights and lax opportunities to have freedom. At the end of the day, we (who are black people) desire true independence and real freedom worldwide. The problem is that we need to do more than eliminate Jim Crow apartheid. We need to provide decent jobs and improve the social conditions of the entire people. Political and economic power should be in the hands of the people. The real definition of a revolution is a radical change in society where the people have the power to control their own destinies socially, politically, and economically (with a radical redistribution of political and economic power). You can't have justice and true social equality without economic justice. Also, there is no solution without the end of the system of white racism point blank period exclamation point. Dr. King went to Chicago in 1966 to promote housing rights for black residents and true justice. He witnessed thousands of white reactionary racists wanted to hurt him. He was hit in the head with a rock. Therefore, Dr. King wanted to promote economic justice and an end to racist practices in society. Also, Dr. King wanted to promote the greatness of black personhood as he was right to proclaim publicly that Black is Beautiful. Dr. King also talked about the necessity to help the poor (to eradicate poverty with the Poor People's Campaign) and to have solidarity with international movements against colonialism and imperialism overseas.

By 1966, Kwame Ture promoted the call for Black Power. Black Power was one of the most praised and debated movements of the overall black freedom struggle. It means many things to be many people. It has been slandered as racist by far-right extremists and even some establishment liberals back then. Richard Wright wrote about Black Power long before 1966, but Kwame Ture was the first person to modernize it by 1966 when he called for it in Greenwood, Mississippi. In Mississippi, Kwame Ture, Dr. King, and other civil rights leaders came to defend the rights of black people after a black man was shot in the street. Black Power is the view that black people have the right to own and control the resources in their communities to gain political, economic, cultural, and social power to benefit black people collectively. There are many factions of the Black Power Movement. Some Black Power advocates were more conservative who wanted black capitalism (which was supported by President Richard Nixon in his 1968 Presidential campaign) or a piece of the action. Many of them were in the Republican Party and embraced conservative nationalism. This issue is that many conservative nationalists ignore the necessity to deal with environmental issues, health care, economic inequality, and other progressive issues that benefit black people collectively. The conservative black nationalists may use some "radical rhetoric," but some of them represented a rival middle class faction that doesn't oppose the current capitalist system (just seeking a piece of the pie in that capitalist system, which does nothing to eradicate poverty and economic exploitation. That is a profound contradiction, because an economic and political system based on the exploitation of human beings in a competitive, selfish mechanism can never enact true liberation for all). This doesn't mean that Stalinist Communism is great, as Stalinist Communism makes a human just a cog in the wheel of the state. The state should be controlled by the people, not by a select few to limit human creativity. As Dr. King rightfully said, Capitalists forget that life is social, and Communism forget that life is individual, so we need independence, not the worship of Communism or Capitalism. Dr. King gave a nuanced view of Black Power saying that black people need economic and political power while he rejected separatism.

The progressive side of the Black Power movement had been represented by the Black Panther Party of Self-Defense (which existed in Oakland, California by October 1967. Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton found that Black Panther Party for Self Defense) and other organizations. The Black Panther Party represented a natural evolution found in the black freedom struggle that wanted more human rights beyond just civil rights. Regardless of the diversity of thought found in the black community, we all desire the same goal (which is which is freedom, justice, and equality for black people and the rest of the human race). The growth of Black Power and Black Nationalist ideologies were prominent from 1966 onward in Civil Rights circles. SNCC would evolve and ally with the Black Power movement. Power. On July 4, 1966, the 23rd annual convention of the Congress on Racial Equality or CORE adopted Black Power as its political slogan for the U.S. civil rights movement. The convention also adopted resolutions opposing U.S. military involvement in the Vietnam War and offered support for draft resisters. Its new national director was Floyd D. McKissick. He criticized President Johnson and the more conservative civil rights organizations. He also invited members of the Nation of Islam to the conference, who attended dressed in military style uniforms. James Farmer by this time retired as director of CORE on March 1, 1966. So, CORE by the late 1960’s, embraced Black Nationalism. Likewise, many moderate civil rights leaders would engage even more in the capitalist system (especially after 1968) to follow the agenda of the corporate 2 party system instead of embracing political independence. The masses of black working people including the poor must be part of the solution making process (to oppose economic exploitation and promote economic, racial, environmental, gender, and social justice) in order for justice to be made real. A real revolutionary wants the end of a corrupt system and replace it with a system of justice.

During this time (of the late 1960’s), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became more progressive. CORE was founded in 1942 as originally a progressive organization. It worked in desegregating interstate travel, voter registration, lunch counter sit-ins, and the Freedom Rides of the early 1960’s. CORE ironically by the end of the 1960’s would be more conservative. For example, CORE supported the Presidency of Richard Nixon (who modernized the War on Drugs, attacked the Black Panthers, and he followed many reactionary policies) in 1968 and 1972. In 1968, Roy Innis declared CORE (which accepted a 1968 grant from the Ford Foundation to work for Carl Stokes’ mayoral campaign in Cleveland) to be a Black Nationalist and separatist organization. Many left wing, liberal people left the organization including the entire Brooklyn branch because of the rightwing turn of CORE (Innis changed CORE from its originally progressive mission. Multinational corporations like Monsanto fund CORE. Innis’ son Nigel Innis continues in his father’s conservative agenda). During the 1970’s, Roy Innis and CORE supported Republicans and he even ran as a Republican political candidate. Roy Innis supported George W. Bush when he was President. Therefore, CORE was into the conservative wing of the black freedom movement by the late 1960’s and in the 1970’s. I disagree with Roy Innis ideologically on many issues. Roy Innis recently passed away at the age of 82 on the day of January 8, 2017, from Parkinson’s disease. I do send condolences to his family and friends. Today, during the 21st century, we are still fighting against imperialism, evil drone strikes, economic inequality, misogyny, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and other evils.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. allied with LBJ on the Voting Rights Act. Yet, Dr. King would later criticize the Johnson administration in public for Johnson shortchanging the War on Poverty while spending billions of dollars on the brutal, unjust Vietnam War. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a great, eloquent speech criticizing the Vietnam War in 1967 in New York City in the Riverside Church. Dr. King was a vociferous opponent of the costly, unjust Vietnam War. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was also right to say on August 31, 1967, in Chicago that capitalism was built on the backs of black slaves as capitalism is highly exploitative and perpetrates injustices against the workers and the poor. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. discussed more about class issues. Dr. King was a great friend of the great, intelligent Marxist historian Brother C.L.R. James. As early as 1966, Dr. King gave a great, accurate criticism of capitalism in the following words to his staff:

“...We are now making demands that will cost the nation something. You can’t talk about solving the economic problem of the Negro without talking about billions of dollars. You can’t talk about ending slums without first saying profit must be taking out of slums. You’re really tampering and getting on dangerous round because you are messing with folk then. You are messing with the captains of industry...Now this means that we are treading in difficult waters, because it really means that we are saying that something is wrong...with capitalism...There must be a better distribution of wealth and maybe America must move towards a Democratic Socialism...”

Voting Rights Challenges

Voting rights have been sacrosanct. Since 1968, many progressive laws and voter suppression laws have existed in American Society. By April 11, 1968, Lyndon Baines Johnson signed the Indian Civil Rights Act into law. This law gave federal courts the power to intervene in intra-tribal disputes. This was controversial. Republican President George W. Bush signed legislation on July 27, 2006, to extend the Voting Rights Act for an additional 25 years. He said that "the right of ordinary men and women to determine their own political future lies at the heart of the American experiment." Previously, the Voting Rights Act was extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982. Even in the 2000s, many far right people tried to suppress the vote in many means. After the Supreme Court 2013 Shelby bad decision (The Shelby County v. Holder case gutted parts of the 1965 Voting Rights Act), many states in the South, the Midwest, etc. started to make election changes in order to take advantage the Court's erosion of the Voting Rights protections. These new laws post-Shelby County decision either made it harder for people to vote or stripped voting rights in other ways. The Shelby County v. Holder June 25, 2013, decision banned jurisdictions with histories of racial discrimination in voting from having to gain federal approval (this is called preclearance) before changing their election laws. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg opposed this policy. Restrictive voting laws increased after 2013. Texas soon made one of the most stringent voting laws in the nation with a voter ID law. The Democratic led House passed HR 4 on December 6, 2019 (to revise parts of the VRA that was gutted after the 2013 Supreme Court decision), but it has not been introduced formally in the current Congress.

When Joe Biden won the Presidency on November 7, 2020, Donald Trump and many of his supporters made the lie that mass voter fraud happened in Atlanta, Detroit, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh (ironically, these cities have a high percentage of African American people in them). After the failed coup d'etat on the U.S. Capitol by insurrectionists on January 6, 2021, voter suppression efforts continued to grow. The Democratic failed to pass HR 1 in the Senate because of the filibuster. HR 1 is the For the People Act that would expand voting via policies like automatic and same day voter registration. On March 25, 2021, Georgia Republican Governor Brian Kemp signed an anti-voting rights bill into law. It is called SB 202. This law imposes new voter ID requirements for absentee ballots, allows state officials to take over local election boards, cuts the use of ballot drop boxes, and make it a crime for people who aren't poll workers to approach voters in line to give them food and water (that is cruel). Democrat Stacey Abrams opposed this law. By May 6, 2021, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a restrictive voting bill into law. This was SB 90 making stricter voter ID requirements by mail, limits who can pick up and return a voter's ballot and bans private funding for elections and other things. This policy was sued by the League of Women Voters of Florida and the Black Voters Matters Fund. The Supreme Court in a 6-3 ruling in Bonovich v. Democratic National Committee promotes racially discriminatory policies. By March 2020, it was reported that Texas leads the South in closing down voting places, making more difficult for African Americans and Latinos to vote. By March 2021, the Republican John Kavanaugh of the Arizona House of Representatives came out to say that everybody shouldn't be voting trying to justify restrictions on voting. John Kavanaugh is wrong period.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott on September 7, 2021, signed SB1 to restrict not only how people vote but when. The law banned overnight early voting hours and drive thru voting. This is popular among people of color. This SB1 is so evil that the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against Texas. The DOJ on December 6, 2021, sued Texas over GOP-approved redistricting maps. The New York University Law School's Brennan Center for Justice documented the voter suppression efforts in Texas and North Carolina. Senators Joe Manchin and Arizona Senator Kyrsten Sinema refused to change Senate rules, even to safeguard voting rights on January 19, 2022. In North Carolina, elected officials eliminated same day registration, scaled back the early voting period, and had a photo ID requirement. A U.S. District Judge Loretta Biggs issued an order banning the photo ID requirement. By February 7, 2022, the Supreme Court restored a Congressional map drawn by Alabama Republicans. Justice Elena Kagan, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor opposed this decision as a disservice to black Alabamians. In late September 2023, ahead of the November election, 26,000 voter registrations were quietly cancelled. Republican Secretary of State was criticism for possible voter suppression by not following the norm of alerting voter groups and by performing the cancellation so close to an election.

Our Continued Fight for Justice in 2025