The National Museum of African American History and Culture (10 Years Later)

Museums not only represent history in a monumental fashion. They give people hope, a sense of purpose, a recognition of the humble, glorious contributions of our ancestors, and a love of truth. Today, we celebrate the 10th year anniversary of the existence of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. It was decades in the making, filled with previous setbacks and a final victory. As an African American, it is an honor to write about this special occasion. Some of our greatest works of art, literature, athletics, technology, and other forms of our glorious black culture as African Americans are found in the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C., too. For example, in the museum, you can witness a Bible owned by Nat Turner, who led a slave rebellion in my state of Virginia in 1831. You can see items owned by Harriet Tubman, Muhammad Ali's boxing gloves, and a chef's jacket worn by Leah Chase, New Orleans' late great chef (or the Queen of Creole Cuisine). The NMAAHC has the gymnastic equipment used by our own 757 icon Gabby Douglas (she was the first African American to win the women's artistic individual all-around gold medal in the 2012 Summer Olympics in London). Today, we have to be clear to defend all legitimate museums, especially those that honor black history and culture. The reason is that Trump and his allies are seeking to whitewash the history of racism and slavery in various museums. That goal from Trump is what I am fundamentally opposed to. So, our real black history and culture is glorious and truly sacrosanct.

Origin

The concept of a national museum to celebrate the culture and history of African Americans have been in existence for over 100 years. In 1915, African American veterans of the Union Army met at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. They wanted a reunion and a parade. They were legitimately outraged with the racial discrimination they had faced. Therefore, the veterans formed a committee to build a memorial to various African American achievements. Their efforts paid off in 1929, when President Herbert Hoover appointed Mary Church Terrell, Mary McLeod Bethune, and 10 others to a commission charged with building a "National Memorial Building" showcasing African-American achievements in the arts and sciences. But Congress did not back the project, and private fundraising also failed. Although proposals for an African-American history and culture museum would be floated in Congress for the next 40 years, none gained more than minimal support. There were proposals for a museum starting to grow among Congress in the early 1970s. By 1981, Congress approved a federal charter for a National Afro-American Museum in Wilberforce, Ohio. The museum was built and funded with private money, opened in 1987. By the early 1980s, Tom Mack (the African-American chairman of Tourmobile, a tourist bus company) founded the National Council of Education and Economic Development (NCEED). Mack's intention was to use the non-profit group to advance his ideas about economic development, education, and the arts in the black community. Emboldened by Congress's action in 1981, Mack began using the NCEED to press for a stand-alone African-American museum in D.C. in 1985.

Mack did not collaborate with other black-led cultural foundations that were working to improve the representation of African Americans by Smithsonian and other federal institutions. Mack contacted Representative Mickey Leland about his idea for a national museum focusing on African Americans, and won his support for federal legislation in 1985. Leland sponsored a non-binding resolution (H.R. 666) advocating an African-American museum on the National Mall, which passed the House of Representatives in 1986. The congressional attention motivated the Smithsonian to improve its presentation of African-American history. In 1987, the National Museum of American History sponsored a major exhibit, "Field to Factory", which focused on the black diaspora out of the Deep South in the 1950s. "Field to Factory" enocuraged Mack to continue purusing a museum. In 1987 and 1988, NCEED began lining up support among black members of Congress for legislation that would establish an independent African-American national history museum in Washington, D.C. But NCEED ran into opposition from the African American Museum Association (AAMA), an umbrella group that represented small local African-American art, cultural, and history museums across the United States. John Kinard, president of the AAMA and co-founder of the Anacostia Community Museum (which became part of the Smithsonian in 1967), opposed NCEED's effort. Kinard argued that a national museum would consume donor dollars and out-bid local museums for artifacts and trained staff. Kinard and the AAMA instead advocated that Congress establish a $50 million fund to create a national foundation to support local black history museums as a means of mitigating these problems.

Others, pointing to the Smithsonian's long history of discrimination against black employees, questioned whether the white-dominated Smithsonian could properly administer an African-American history museum. Lastly, many local African-American museums worried that they would be forced to become adjuncts of the proposed Smithsonian museum. These institutions had fought for decades for political, financial, and academic independence from white-dominated, sometimes racist local governments. Now they feared losing that hard-won independence. In 1988, Rep. John Lewis and Rep. Leland introduced legislation for a stand-alone African-American history museum within the Smithsonian Institution. But the bill faced significant opposition in Congress due to its cost. Supporters of the African-American museum tried to salvage the proposal by suggesting that the Native Indian museum (then moving through Congress) and African-American museum share the same space. But the compromise did not work and the bill died.

Lewis and Leland introduced another bill in 1989. Once more, cost considerations killed the bill. The Smithsonian Institution, however, was moving toward support for a museum. In 1988, an ad hoc group of African-American scholars—most from within the Smithsonian, but some from other museums as well—began debating what an African-American history museum might look like. While the group discussed the issue informally, Smithsonian Secretary Robert McCormick Adams, Jr. publicly suggested in October 1989 that "just a wing" of the National Museum of American History should be devoted to black culture, a pronouncement that generated extensive controversy. The discussions by the ad hoc group prompted the Smithsonian to take a more formal approach to the idea of an African-American heritage museum. In December 1989 the Smithsonian hired nationally respected museum administrator Claudine Brown to conduct a formal study of the museum issue.

Brown's group reported six months later that the Smithsonian should form a high-level advisory board to conduct a more thorough study of the issue. The Brown study was blunt in its discussion of the divisions within the African-American community about the advisability of a stand-alone national museum of African-American culture and history, but also forceful in its advocacy of a national museum of national prominence and national visibility with a broad mandate to document the vast sweep of the African-American experience in the United States. The study was also highly critical of the Smithsonian's ability to adequately represent African-American culture and history within an existing institution, and its willingness to appoint African-American staff to high-ranking positions within the museum.

The Smithsonian formed a 22-member advisory board, chaired by Mary Schmidt Campbell, in May 1990. The creation of the advisory board was an important step for the Smithsonian. There were many on the Smithsonian's Board of Regents who believed that "African-American culture and history" was indefinable and that not enough artifacts and art of national significance could be found to build a museum. On May 6, 1991, after a year of study, the advisory board issued a report in favor of a national museum, and the Smithsonian Board of Regents voted unanimously to support the idea. However, the proposal the regents adopted only called not for a stand-alone institution but a "museum" housed in the East Hall of the existing Arts and Industries Building. The regents also agreed to keep the Anacostia Community Museum a separate facility; to give the new museum its own governing board, independent of existing museums; and to support the proposal for a grant-making program to help local African-American museums build their collections and train their staff. The regents also approved a "collections identification project" to identify donors who might be willing to donate, sell, or loan their items to the proposed new Smithsonian museum.

The Smithsonian created a 22 member advisory board. It was chaired by Mary Schmidt Campbell by May of 1990. This advisory board was created as a very important step for the Smithsonian. There were many on the Smithsonian's Board of Regents who believed that "African-American culture and history" was indefinable and that not enough artifacts and art of national significance could be found to build a museum. I don't agree with that view obviously. On May 6, 1991, after a year of study, the advisory board issued a report in favor of a national museum, and the Smithsonian Board of Regents voted unanimously to support the idea. However, the proposal the regents adopted only called not for a stand-alone institution but a "museum" housed in the East Hall of the existing Arts and Industries Building. The regents also agreed to keep the Anacostia Community Museum a separate facility; to give the new museum its own governing board, independent of existing museums; and to support the proposal for a grant-making program to help local African-American museums build their collections and train their staff. The regents also approved a "collections identification project" to identify donors who might be willing to donate, sell, or loan their items to the proposed new Smithsonian museum.

More plans have taken place during the 1990s. The Smithsonian Board of Regents agreed in September 1991 to draft museum legislation. It was submitted as a bill to Congress in February 1992. The bill was criticized by Tom Mack and others for putting the museum in a building that was too small and old to properly house the intended collection, and despite winning approval in both House and Senate committees the bill died once more. In 1994, Senator Jesse Helms refused to allow the legislation to come to the Senate floor (voicing both fiscal and philosophical concerns) despite bipartisan support. For those who don't know, Jesse Helms was a far right extremist who shown hositility towards black people for decades. Helms was a racist. In 1995, citing funding issues, the Smithsonian abandoned its support for a new museum and instead proposed a new Center for African American History and Culture within organization. The Smithsonian's new Secretary, Ira Michael Heyman, openly questioned the need for "ethnic" museums on the National Mall. Many, including Mary Campbell Schmidt, saw this as a step backward, a characterization Smithsonian officials strongly disputed. To demonstrate its support for African-American history preservation, the Smithsonian held a fundraiser in March 1998 for the new center which raised $100,000 (~$179,001 in 2024). Heymann left the Smithsonian in January 1999. In the meantime, other cities moved forward with major new African-American museums. The city of Detroit opened a $38.4 million, 120,000 sq ft (11,000 m2) Museum of African-American History in 1997, and the city of Cincinnati was raising funds for a $90 million, 157,000 sq ft (14,600 m2) National Underground Railroad Freedom Center (which broke ground in 2002). In 2000, a private group—upset with congressional delays—proposed constructing a $40 million (~$69 million in 2024), 400,000 sq ft (37,000 m2) museum on Poplar Point, a site on the Anacostia River across from the Washington Navy Yard.

In 2001, Lewis and Representative J. C. Watts re-introduced legislation for a museum in the House of Representatives. Under the leadership of its new Secretary, Lawrence M. Small, the Smithsonian Board of Regents reversed course yet again in June 2001 and agreed to support a stand alone National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Smithsonian asked Congress to establish a federally funded study commission. Congress swiftly agreed, and on December 29, President George W. Bush signed legislation establishing a 23-member commission to study the need for a museum, how to raise the funds to build and support it, and where it should be located. At the signing ceremony, the president expressed his opinion that the museum should be located on the National Mall.

The study commission's work took nearly two years, not the anticipated nine months. In November 2002, in anticipation of a positive outcome, the insurance company AFLAC donated $1 million (~$1.66 million in 2024) to help build the museum. On April 3, 2003, the study commission released its final report. As expected, the commission said a museum was needed, and recommended an extremely high-level site: A plot of land adjacent to the Capitol Reflecting Pool, bounded by Pennsylvania and Constitution Avenues NW and 1st and 3rd Streets NW. The commission ruled out establishing the museum within the Arts and Industries Building, concluding renovations to the structure would be too costly. It considered a site just west of the National Museum of American History and a site on the southwest Washington waterfront, but rejected both. The commission considered whether the museum should have an independent board of trustees (similar to that of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum) or a board answerable both to the Smithsonian and independent trustees (similar to that of the National Gallery of Art), but rejected these approaches in favor of a board appointed by and answerable only to the Smithsonian Board of Regents. The commission proposed a 350,000 square-foot museum that would cost $360 million to build. Half the construction funds would come from private money, half from the federal government. Legislation to implement the commission's report was sponsored in the Senate by Sam Brownback and in the House by John Lewis.

As Congress considered the legislation, the museum's location became the major sticking point. Various members of the public, Congress, and advocacy groups felt the Capitol Hill site was too prominent and made the National Mall look crowded. Alternative proposed sites included the Liberty Loan Federal Building at 401 14th Street SW and Benjamin Banneker Park at the southern end of L'Enfant Promenade. This controversy threatened to kill the legislation. To save the bill, backers of the museum said in mid-November 2003 that they would abandon their push for the Capitol Hill site. The compromise saved the legislation: The House passed the "National Museum of African American History and Culture Act" (Pub. L. 108–184 (text) (PDF)) on November 19, and the Senate followed suit two days later. President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on December 16. The legislation appropriated $17 million for museum planning and a site selection process, and $15 million for educational programs. The educational programs included grants to African-American museums to help them improve their operations and collections; grants to African-American museums for internships and fellowships; scholarships for individuals pursuing careers African-American studies; grants to promote the study of modern-day slavery throughout the world; and grants to help African-American museums build their endowments. The legislation established a committee to select a site, and required it to report its recommendation within 12 months. The site selection committee was limited to studying four sites: The site just west of the National Museum of American History, the Liberty Loan Federal Building site, Banneker Park, and the Arts and Industries Building.

To his credit, President George W. Bush endorsed placing the museum on the National Mall on February 8, 2005. The site selection committee did not issue its recommendation until January 31, 2006—a full 13 months later. It recommended the site west of the National Museum of American History. The area was part of the Washington Monument grounds but had been set aside for a museum or other building in the L'Enfant Plan of 1791 and the McMillan Plan of 1902. The United States Department of State originally planned to build its headquarters there in the early 20th century, and the National World War II Memorial Advisory Board had considered the parcel in 1995. On March 15, 2005, the Smithsonian named Lonnie G. Bunch III to be the Director of the National African American Museum of History and Culture.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture Council (the museum's board of trustees) sponsored a competition in 2008 to design a 350,000 sq ft (33,000 m2) building with three stories below-ground and five stories above-ground. The building was limited to the 5-acre (20,000 m2) site chosen by the site selection committee, had to be LEED Gold certified, and had to meet stringent federal security standards. The cost of construction was limited to $500 million ($730,216,383 in 2024 dollars). The competition criteria specified that the winning design had to respect the history and views of the Washington Monument as well as demonstrate an understanding of the African-American experience. The winning design was required to reflect optimism, spirituality, and joy, but also acknowledge and incorporate the forms of anti-black oppression found in the African-American experience. The museum design was required to function as a museum but also be able to host cultural events of various kinds. Hundreds of architects and firms were invited to participate in the design competition. Six firms were chosen as finalists. The design submitted by the Freelon Group/Adjaye Associates/Davis Brody Bond won the design competition. The above-ground floors featured an inverted step pyramid surrounded by a bronze architectural scrim, which reflected a crown used in Yoruba culture; specifically, these three stacked trapezoidal shapes were inspired by the top of an Olowe of Ise sculpture which is now on display inside the museum.

Under federal law, the National Capital Planning Commission, the United States Commission of Fine Arts, and the D.C. Historic Preservation Commission all have review and approval rights over construction in the metropolitan D.C. area. As the design went through these agencies for approval, it was slightly revised. The building was moved toward the southern boundary of its plot of land, to give a better view of the Washington Monument from Constitution Avenue. The size of the upper floors were shrunk by 17 percent. Although three upper floors were permitted (instead of just two), the ceiling height of each floor was lowered so that the overall height of the building was lowered. The large, box-like first floor was largely eliminated. Added to the entrance on Constitution Avenue were a pond, garden, and bridge, so that visitors would have to "cross over the water" like slaves did when they came to America. The Smithsonian estimated in February 2012 that museum would to open in 2015. Until then, the museum would occupy a gallery on the second floor of the National Museum of American History. On June 10, 2013, media magnate Oprah Winfrey donated $12 million (~$15.9 million in 2024) to the NMAAHC. This was in addition to the $1 million (~$1.45 million in 2024) she donated to the museum in 2007. The Smithsonian said it would name the NMAAHC's 350-seat theater after her. The GM Foundation announced a $1 million (~$1.3 million in 2024) donation to the museum on January 22, 2014, to fund construction of the building and design and install permanent exhibits.

From 2012 to 2016, the construction of the NMAAHC existed in a strong fashion. There were the facade's scrim in the structure. It was influenced by designs from Charleston, South Carolina and New Orleans, Louisiana. There were many design changes. The museum's groundbreaking ceremony took place on February 22, 2012. President Barack Obama and museum director Bunch were among the speakers in the ceremony. Actress Phylicia Rashad was the Master of Ceremonies for the event, which also featured poetry and music performed by Denyce Graves, Thomas Hampson, and the Heritage Signature Chorale. Clark Construction Group, Smoot Construction, and H.J. Russell and Company won the contract to build the museum. The architectural firm of McKissack & McKissack (which was the first African American-owned architectural firm in the United States) provided project management services on behalf of the Smithsonian and acted as liaison between the Smithsonian and public utilities and D.C. government agencies. Guy Nordenson and Associates and Robert Silman Associates were the structural engineers for the project.

The NMAAHC became the deepest museum on the National Mall. Excavators dug 80 ft (24 m) below grade to lay the foundations, although the building itself will be only 70 ft (21 m) deep. The museum is located at a low point on the Mall, and groundwater puts 27.78 psi (191.5 kPa) on the walls. To compensate, 85 US gal (320 L) per minute of water were pumped out every day during construction of the foundation and below-grade walls, and a slurry of cement and sand was injected into forms to stabilize the site. Lasers continually monitored the walls during construction for any signs of bulging or movement. The first concrete for the foundations was poured in November 2012. As the lower levels were completed, cranes installed a segregated railroad passenger car and a guard tower from the Louisiana State Penitentiary on November 17, 2013. These items were so large that they could not be dismantled and installed at a later date. Instead, the museum had to be built around them. By late December 2013, construction was just weeks from finishing the five basement levels, and above-ground work was scheduled to begin in late January 2014. At that time, the Smithsonian estimated the museum would be finished in November 2015. The construction of the museum had floors, reinforced concrete with columns. The building had massive steel elements. It had girders being complex. It had an elliptical monumental staircase that ran continually between above ground floors. It weighs more than 80,000 pounds. Ozwald Boateng OBE, a jury member, made a statement expressing his thoughts on the NMAAHC: "We couldn't look any further than the Smithsonian for the overall award. It is a project of beautiful design, massive cultural impact, delivers an emotional experience, and has a scale deserve of this major award." The topping out of the museum existed in October 2014.

That same month, the Smithsonian announced that the National Museum of African American History and Culture had received $162 million in donations toward the $250 million cost of constructing its building. To bolster the fundraising, the Smithsonian said it would contribute a portion of its $1.5 billion capital campaign to help complete the structure. The entire steel superstructure and all above-ground concrete pouring were complete in January 2015. Glass for the windows and curtain walls began to be placed that same month, with glass enclosure of the building complete on April 14, 2015. That same day, the first of the structure's 3,600 bronze-colored panels for the building's corona were installed. A worker was severely injured at the construction site on June 3, 2015, when scaffolding on the roof collapsed on top of him. 35-year-old Ivan Smyntyna was rushed to a local hospital, where he later died. The 350,000 sq ft (33,000 m2) building has a total of 10 stories (five above and five below ground). Then, the next event would be the museum's opening day on September 24, 2016.

The Historic 2016 Opening

The opening took place by 2016. President Barack Obama dedicated the museum. There were special events planned, too. NMAAHC officials said that construction scaffolding around the exterior of the building should come down in April 2016, at which time some of the more dust-and-humidity resistant artifacts and displays could be installed. Installation of more delicate items would wait until the building's environmental controls had stabilized the interior humidity and removed most of the dust from the air. The museum identified 3,000 items in its collections, which would form 11 initial exhibits. More than 130 video and audio installations would be installed as part of these exhibits. By January 2016, the museum received a 10-million-dollar gift from David Rubenstein, the CEO of The Carlyle Group and a Smithsonian regent. There was a 1 million donation from Wells Fargo. As of January 30, 2016, the museum still needed to raise $40 million toward its $270 million construction goal. Two unique documents, both signed by President Abraham Lincoln, would be loaned to the museum for its opening. These are commemorative copies of the 13th Amendment and the Emancipation Proclamation, of which only a limited number were printed. Few of these have survived. David Rubenstein purchased both items in 2012. Microsoft announced a 1 million donation to the museum by late March 2016. People debated whether items about the career of Bill Cosby will be in the museum as Bill Cosby has been accused of sexual assault by dozens of women. In response to the resulting controversy, the museum added the following sentence to its description of Cosby's career: "In recent years, revelations about alleged sexual misconduct have cast a shadow over Cosby's entertainment career and severely damaged his reputation." The following are some of the words of President Barack Obama in detailing his dedication to the National Museum of African American History and culture by September 24, 2016:

"...And so this national museum helps to tell a richer and fuller story of who we are. It helps us better understand the lives, yes, of the President, but also the slave; the industrialist, but also the porter; the keeper of the status quo, but also of the activist seeking to overthrow that status quo; the teacher or the cook, alongside the statesman. And by knowing this other story, we better understand ourselves and each other. It binds us together. It reaffirms that all of us are America -- that African-American history is not somehow separate from our larger American story, it's not the underside of the American story, it is central to the American story. That our glory derives not just from our most obvious triumphs, but how we’ve wrested triumph from tragedy, and how we've been able to remake ourselves, again and again and again, in accordance with our highest ideals.

I, too, am America.

The great historian John Hope Franklin, who helped to get this museum started, once said, “Good history is a good foundation for a better present and future.” He understood the best history doesn’t just sit behind a glass case; it helps us to understand what’s outside the case. The best history helps us recognize the mistakes that we’ve made and the dark corners of the human spirit that we need to guard against. And, yes, a clear-eyed view of history can make us uncomfortable, and shake us out of familiar narratives. But it is precisely because of that discomfort that we learn and grow and harness our collective power to make this nation more perfect.

That’s the American story that this museum tells -- one of suffering and delight; one of fear but also of hope; of wandering in the wilderness and then seeing out on the horizon a glimmer of the Promised Land...So enough talk. President Bush is timing me. (Laughter.) He had the over/under at 25. (Laughter.) Let us now open this museum to the world. Today, we have with us a family that reflects the arc of our progress: the Bonner family -- four generations in all, starting with gorgeous seven-year-old Christine and going up to gorgeous 99-year-old Ruth. (Applause.)

Now, Ruth’s father, Elijah Odom, was born into servitude in Mississippi. He was born a slave. As a young boy, he ran, though, to his freedom. He lived through Reconstruction and he lived through Jim Crow. But he went on to farm, and graduate from medical school, and gave life to the beautiful family that we see today -- with a spirit reflected in beautiful Christine, free and equal in the laws of her country and in the eyes of God.

So in a brief moment, their family will join us in ringing a bell from the First Baptist Church in Virginia -- one of the oldest black churches in America, founded under a grove of trees in 1776. And the sound of this bell will be echoed by others in houses of worship and town squares all across this country -- an echo of the ringing bells that signaled Emancipation more than a century and a half ago; the sound, and the anthem, of American freedom.

God bless you all. God bless the United States of America. (Applause)."

Google donated $1 million (~$1.28 million in 2024) to the museum in early September 2016. The technology firm had previously worked with the NMAAHC to create a 3D interactive exhibit which allows visitors to see artifacts in a close-up, 360-degree view using their mobile phone. The 3D exhibit was created by designers and engineers from the Black Googler Network. On September 16, 2016, violinist Edward W. Hardy composed and performed Evolution - Inspired by the Evolution of Black Music for the Congressional Black Caucus at a Google sponsored event in Howard Theatre. This event was a part of the opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. On September 23, 2016, The Washington Post reported that Robert F. Smith, the founder, chairman, and CEO of Vista Equity Partners, had given $20 million (~$25.5 million in 2024) to the NMAAHC. The gift was second-largest in the museum's history, exceeded only by the $21 million donated by Oprah Winfrey.

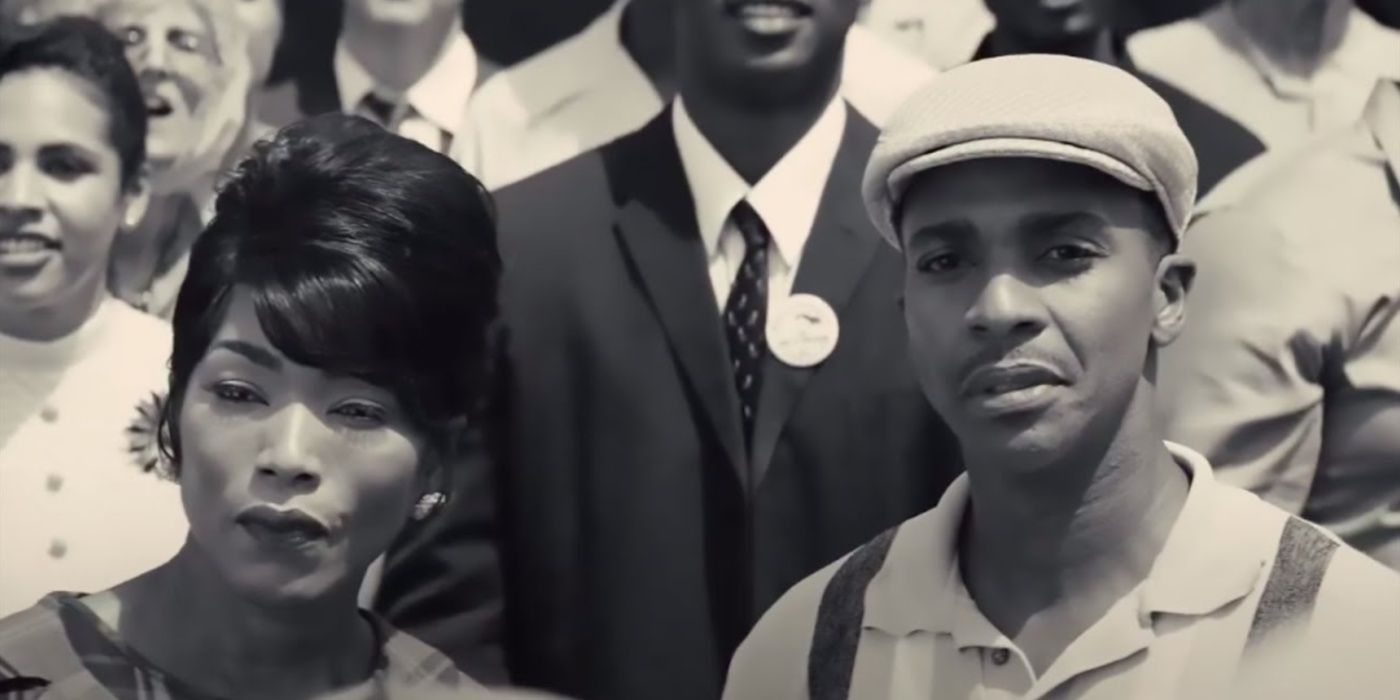

Ava DuVernay was commissioned by the museum to create a film which debuted at the museum's opening on September 24, 2016. This film, August 28: A Day in the Life of a People (2016), tells of six significant events in African American history that happened on the same date, August 28. The 22-minute film stars Lupita Nyong'o, Don Cheadle, Regina King, David Oyelowo, Angela Bassett, Michael Ealy, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, André Holland and Glynn Turman. Events depicted include William IV's royal assent to the UK Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, the 1955 lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi, the release of Motown's first number-one song, "Please Mr. Postman" by The Marvellettes, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s 1963 "I Have a Dream" speech, the landfall of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and the night then-senator Barack Obama accepted the Democratic nomination for president at the 2008 Democratic National Convention.

On September 24, 2016, President Barack Obama formally opened the new museum along with four generations of the Bonner family, from 99-year-old Ruth Bonner to Ruth's great-granddaughter Christine. Together with the Obamas, Ruth and her family rang the Freedom Bell (rather than cut a ribbon) to officially open the museum. The bell came from the first Baptist church organized by and for African Americans, founded in 1776 in Williamsburg, Virginia, where, at the time, it was unlawful for black people to congregate or preach. During his speech at the museum's opening, Obama shed tears discussing his thoughts on visiting the museum with future grandchildren. The opening ceremony also included a speech by Muriel Bowser and a performance by Angélique Kidjo, who is a prominent African singer.

The total cost of the museum's design, construction, and installation of exhibits was $540 million ($707,495,840 in 2024 dollars). By the time the museum's founding fundraising campaign had ended, the NMAAHC had raised $386 million ($505,728,508 in 2024 dollars), 143 percent more than its goal of $270 million.

Vital Artifacts

There are tons of exhibits, artifacts, and digital images found in the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The museum has the camera used by Rev. Henry Clay Anderson during the 1960s to record African Americans living their lives in Greensville, Mississippi. The museum has the famous Croix de Guerre award that was placed on Corporal Lawrence McVey of the 368th Infantry. That was an African American regiment known as the Harlem Hellfighters that fought the fascist Axis enemy during World War II. There is the old 19th-century Bible that was possibly read by Nat Turner found in the NMAAHC, too. The first edition of African American poet Phillis Wheatley has been placed in the museum. She wrote many verses while she was enslaved. The pottery of the slave Dave the Potter of the 1800s is found in the location. The famous eight-by-four bill poster of June 1863 to encourage black people to fight for the Union during the American Civil War (which was signed by Frederick Douglas and 33 other people) is found in the museum. The museum has portraits of Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglas, Union solider Corporal Prince Shorts of the 25th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, and Pauline Cookman (who served in the Women's Army Corps, a U.S. Army branch created in World War II. It was segregated until 1950).

The Defense of Museums

It is always important to defend black museums and any museums that show the true history of America. Trump has gone out of his way to attack the NMAAHC, because that museum has shown the truth about the evil of slavery and the evil of white racism. Many conservatives believe in the myth that exposing white racism is somehow anti-American. What is truly anti-American is to whitewash American history for the sake of promoting conservative political correctness. Black museums are doing their best to record authentic history. The Trump administration used the lie that the Smithsonian museums promote divisive language to describe real American history. The truth is never divisive. It's just reality. For example, the following facts: white racism is a reality, black Americans made great contributions to society, people have every right to expose slavery and the legacy of slavery, and we must support civil rights, including human rights in the Universe. Museums should have independent power to research information and present wisdom to all of the people. Other museums like The Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, have great research and exhibits to link slavery to convict leasing, lynching, segregation, and mass incarceration. There is the International Slavery Museum in the United Kingdom. There is the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana that exposes the brutality of slavery and outlines the stories of enslaved human beings, too. We should never minimize slavery. Doing that only weakens civic literacy, disrespects descendants and survivors of slavery, harms American culture, and builds distrust of institutions. It is important to note that black history is American history. There is no America without us black people. Therefore, it is very imperative for us to use our power to defend black museums.

The Legacy of the NMAAHC

It has been 10 years since the creation of the Smithsonian National Museum of African History and Culture. It is time to refute the lie that the term of African American was invented by Jesse Jackson. The truth is that Malcolm X used the phrases of Afro-American and African American back in the 1960s. The term of African American has been used since the 1700s, and I love that phrase. The reason is that it encapsulates our African heritage. It embodies being against the politically correct lie that we are all just Americans and nothing more. The truth is that we have complex histories, various cultures, and have one origin from Africa, as black human beings (so, I respect the global black African Diaspora too. Africans, Afro-Caribbeans, Afro-Europeans, Afro-Asians, etc. made great achievements in the world as well. I want to make that point perfectly clear). The NMAAHC has rare artifacts, digital displays, and emotional images that should motivate all of us (irrespective of color) to stand up for justice (and support all legitimate moral convictions). In our time, far-right extremists, manosphere propagandists, and other bigots (who are filled with hatred and animosity towards progressive fighters for social change) want to minimize or whitewash the contributions of black people, women, and all other people of color, and other minorities. Yet, we won't be intimidated by the forces of evil. Goodness trumps injustice. The culture of our black lives is sacrosanct. Museums that tell our black stories must be protected because our black history matters, and it allows present and future generations to realize that we are not going anywhere. That's real talk. For the record, we black Americans have a strong, vibrant culture. For example, African American culture is reflected in the literature of Langston Hughes to Nora Zeal Hurston. It involves the athleticism of Michael Jordan, Allyson Felix, Serena Williams, LeBron James, Jackie Robinson, and Jackee Joyner-Kersee. African American culture focuses on music too from Aretha Franklin to Levi Stubbs. It deals with our charisma, our inventive spirt, and our intellectual creativity that can never be duplicated. Like always, Black is Beautiful, we want all black people globally to be free and have justice, and our legacy will live on forever and ever. Selah.

By Timothy

.jpg/960px-National_Museum_of_African_American_History_and_Culture_(97874).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment