Philadelphia

Philadelphia is a Northeastern city with a lot of history and a grand amount of culture. It is the largest city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. With its population of over 1,560,297 people, it is the fifth most populous city in the United States of America. It is found at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. Its metropolitan area is filled with about 7.2 million people. History abounds in the majestic city of Philadelphia. It is not only the place where the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. It is home to a strong civil rights movement and it is home to a strong multicultural population, which is representative of the magnificent diversity of American society. Philadelphia and the state of Pennsylvania in general is home to a wide spectrum of art, music, and other forms of cultural expression. Philadelphia has 141.6 square miles. I love geography too, so it is always important to also acknowledge the surrounding locations around Philadelphia in order to gauge a great context about the excellent city of Philly. Camden, New Jersey is directly east of Philadelphia from across the Delaware River. To the southwest of Philadelphia is Wilmington, Delaware. Northeast of Philadelphia is Trenton, New Jersey and New York City. Directly southeast of Philly lies Atlantic City (which is on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean). Pittsburgh is far west of Philadelphia as well. Philadelphia is major tourist spot for people from across America and from across the world as well. It has attracted over 39 million domestic tourists in 2013, which has generated $10 billion. Philadelphia not only has gorgeous skyscrapers and an inspirational history. Today in 2016, Philadelphia has a gross domestic product of $388 billion. That ranks Philadelphia as ninth among world cities and fourth in America. Girard Estates, West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, South Philadelphia, Kensington, and other neighborhoods show diversity and strength. Its skyline is growing. Philadelphia's culture is magnificent. It has strong, resilient people who love the essence of human brotherhood and human sisterhood too. Hoagies, cheesesteak, and other cuisine are enjoyed in Philly. The Liberty Bell, Independence Hall, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art outline the greatness of Philadelphia. We remember the sacrifice of so many of our ancestors who fought, sacrificed for liberty, and advanced a dedication to justice. Philadelphia has been in existence since October 27, 1682. Also, we want a better future for ourselves and for our descendants. That's our profound destiny. We cherish joy and a tranquil society. Likewise, we realize that in order to establish a more perfect union, we have to use profound, consistent, and firm activism to enrich the lives of humanity. Therefore, Philadelphia is a strong city with an excellent cultural heritage.

The Early Period

Before Philadelphia was created, the area was inhabited by the Lenape (Delaware) Native Americans. The village of Nitapèkunk was found in the Fairmount Park area. Nitapèkunk means “Place that is easy to get to.” The villages of Pèmikpeka (meaning “Where the water flows”) and Shackamaxon were located on the Delaware River. The Delaware River Valley was called Suyd or “South” River or Lënapei Sipu back then. European colonization of the Delaware River started in 1609. This was when a Dutch expedition led by Henry Hudson first entered the river in search of the Northwest Passage (or a path trying to go from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean). The Valley included the future location of Philadelphia was part of the New Netherland claim of the Dutch. Dutch explorer Cornelius Jacobsen Mey (after whom Cape May, New Jersey is named after) shared the shoals (a natural body of land) of Delaware Bay during the 1620’s. The Dutch built a fort on the west side of the bay at Swanendael. In 1637, Swedish, Dutch, and German stockholders created the New Sweden Company to trade for furs and tobacco in North America.

Under the command of Peter Minuit, the company's first expedition sailed from Sweden late in 1637 in two ships, Kalmar Nyckel and Fogel Gri. Minuit had been the governor of the New Netherland from 1626 to 1631. Resenting his dismissal by the Dutch West India Company, he had brought to the new project the knowledge that the Dutch colony had temporarily abandoned its efforts in the Delaware Valley to focus on the Hudson River valley to the north. (The Hudson was known to the Dutch as the Noort, or "North" river relative to "South" of the Delaware.) Minuit and his partners further knew that the Dutch view of colonies held that actual occupation was necessary to secure legal claim. The ships reached Delaware Bay in March 1638, and the settlers began to build a fort at the site of present-day Wilmington, Delaware. They named it Fort Christina, in honor of the twelve-year-old Queen Christina of Sweden. It was the first permanent European settlement in the Delaware Valley. Part of the colony would include land on the west side of the Delaware River from just below the Schuylkill River. Johan Björnsson Printz, who it had been ennobled, was appointed to be the first royal governor of New Sweden, arriving in the colony on February 15, 1643. In his ten year rule, the administrative center of New Sweden was moved north to Tinicum Island (to the immediate SW of today’s Philadelphia). That is the place where he built Fort New Gothenburg and his own manor house was called by him the Printzhof. The first English settlement occurred about 1642 when 50 Puritan families from the New Haven Colony in Connecticut. They were led by George Lamberton who tried to form a theocracy at the mouth of the Schukylkill River. The New Haven Colony had earlier struck a deal with Lenape to buy much of New Jersey south of present day Trenton. The Dutch and Swedes in the area burned the English colonists’ buildings. A Swedish court under Swedish Governor Johan Björnsson Printz convicted Lamberton of “trespassing, conspiring with the Native Americans.” The offshoot New Haven colony received no support. The Puritan Governor John Winthrop said that it was dissolved owing to the summer “sickness and mortality.” This disaster contributed to New Haven’s losing control of its area to the larger Connecticut Colony.

In 1644, New Sweden supported the Susquehannock in their victory in a war against the English Province of Maryland (led by General Harrison II). The Dutch never recognized the legitimacy of the Swedish claim and in the late summer of 1655, Director General Peter Stuyvesant (of New Amsterdam) mustered a military expedition to the Delaware Valley. He wanted to subdue the rogue colony of New Sweden. Though the colonists had to recognize the authority of New Netherland, the Dutch terms were tolerant. The Swedish and Finnish settlers continued to enjoy a much local autonomy, having their own militia, religion, court, and lands. This official status lasted until the English conquest of New Netherland in October 1664, and continued unofficially until the area was included in William Penn's charter for Pennsylvania in 1682. By 1682, the area of modern Philadelphia was inhabited by about 50 Europeans, mostly subsistence farmers.

In 1681, as part of repayment of a debt, Charles II of England granted William Penn a charter for what would become the Pennsylvania Colony. Shortly after receiving the charter, Penn said that would lay out: “a large Towne or Citty in the most convenient place upon the Delaware River for health & Navigation.” Penn wanted the city to live peacefully in the area, without a fortress or walls. So, he bought land from the Lenape. There is a legend that Penn made a treaty of friendship with Lenape chief Tammany under an elm tree at Shackamaxon. That is known as the city’s Kensington District. Penn wants a city where all people regardless of religion could worship freely and live together. Penn was a Quaker. So, he experienced religious persecution. He also planned that the city's streets would be set up in a grid, with the idea that the city would be more like the rural towns of England than its crowded cities. The homes would be spread far apart and surrounded by gardens and orchards. The city granted the first purchasers land along the Delaware River for their homes. It had access to the Delaware Bay and Atlantic Ocean, and became an important port in the Thirteen Colonies. He named the city Philadelphia (philos, "love" or "friendship", and adelphos, "brother"); it was to have a commercial center for a market, state house, and other key buildings. Penn sent three commissioners to supervise the settlement. They were to set aside 10,000 acres of land for the city. The commissioners bought land from the Swedes at the settlement of Wicaco and from there began to lay out the city toward the north.

The area went about a mile along the Delaware River between South and Vine Streets. Penn’s ship anchored off the coast of New Castle, Delaware on October 27, 1682. He arrived into Philadelphia a few days after that. He expanded the city west to the bank of the Schuylkill River for a total of 1,200 acres (or 4.8 km2). Except for the two widest streets, High (now Market) and Broad, the streets were named after prominent landowners who owned adjacent lots. The streets were renamed in 1684; the ones running east-west were named after local trees (Vine, Sassafras, Mulberry, Cherry, Chestnut, Walnut, Locust, Spruce, Pine, Lombard, and Cedar) and the north-south streets were numbered. Within the area, four squares (now named Rittenhouse, Logan, Washington and Franklin) were set aside as parks open for everyone. Penn designed a central square at the intersection of Broad and what is now Market Street to be surrounded by public buildings. Some of the first settlers lived in caves dug out of the river bank, but the city grew with construction of homes, churches, and wharves. The new landowners did not share Penn's vision of a non-congested city. Most people bought land along the Delaware River instead of spreading westward towards the Schuylkill. The lots they bought were subdivided and resold with smaller streets constructed between them. Before 1704, few people lived west of Fourth Street.

Growth

Philadelphia grew quickly during the 17th and 18th centuries. It was just a few hundred people to over 2,500 people in 1701. Most people in Philadelphia back then were English, Welsh, Irish, Germans, Swedes, Finns, Dutch, and African people. There were African slaves in Philadelphia too. Before William Penn left Philadelphia for the last time on October 25, 1701, he issued the Charter of 1701. That charter made Philadelphia a city and gave the mayor, aldermen, and councilmen the authority to issue laws and ordinances. Also, they had the power to regulate markets and fairs. The first known Jewish resident of Philadelphia was Jonas Aaron. He was a German who moved into the city in 1703. He is mentioned in an article entitled "A Philadelphia Business Directory of 1703," by Charles H. Browning. It was published in The American Historical Register, in April, 1895. Philadelphia became an important trading center and a major port. In the beginning, the city’s main source of trade was with the West Indies. The West Indies had established sugar cane plantations. This area was part of the evil Triangle Trade. The Triangular Trade was about resources grown in the Americas, shipped into Britain (and Europe), and involving slaves from Africa (European imperialism exploited slaves in order for these imperialists to get the resources in the Americas). During Queen Anne's War (1702 and 1713) with the French, trade was cut off to the West Indies, hurting Philadelphia financially. The end of the war brought brief prosperity to all of the British territories, but a depression in the 1720's stunted Philadelphia's growth. The 1720's and '30's saw immigration from mostly Germany and northern Ireland to Philadelphia and the surrounding countryside. The region was developed for agriculture and Philadelphia exported grains, lumber products and flax seeds to Europe and elsewhere in the American colonies; this pulled the city out of the depression. Philadelphia’s promotion of religious tolerance attracted many other religions beside the Quakers. Mennonites, Pietists, Anglicans, Catholics, and Jewish people moved into Philadelphia. They soon outnumbered the Quakers.

The Quakers still continued to be powerful economically and politically. Political tensions existed between and within the religious groups, which also had national connections. Riots in 1741 and 1742 took place over high bread prices and drunken sailors. In October 1742 and the "Bloody Election" riots, sailors attacked Quakers and pacifist Germans, whose peace politics were strained by the War of Jenkins' Ear. The city was plagued by pickpockets and other petty criminals. Working in the city government had such a poor reputation that fines were imposed on citizens who refused to serve an office after being chosen. One man fled Philadelphia to avoid serving as mayor. During the first half of the 18th century (like other American cities), Philadelphia was filled with garbage, etc. There were animals littering the streets. Many roads were unpaved and rainy seasons had many roads impassable. Early attempts to improve quality of life were ineffective because laws were poorly enforced. By the 1750's, Philadelphia was turning into a major city. Things changed. Christ Church and the Pennsylvania State House, better known as Independence Hall, were built. Streets were paved and illuminated with oil lamps. Philadelphia’s first newspaper, Andrew Bradford's American Weekly Mercury, began publishing on December 22, 1719. The city also developed culturally and scientifically. Schools, libraries, and theaters were established early on in Philadelphia. James Logan arrived in Philadelphia in 1701 as a secretary for William Penn. He was the first to help establish Philadelphia as a place of culture and learning. Yet, the injustice of slavery still existed in Philadelphia back then.

Logan was the mayor of the city during the early 1720’s. He created one of the largest libraries in the colonies. He also helped guide other prominent Philadelphia residents like the botanist John Bartram and Benjamin Franklin. Benjamin Franklin arrived in Philadelphia in October 1723 and would play a large role in the city’s development. To help protect the city from fire, Franklin founded the Union. In the 1750's Franklin was named one of the city's post master generals and he established postal routes between Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and elsewhere. He helped raise money to build the American colonies' first hospital, which opened in 1752. That same year the College of Philadelphia, another project of Franklin's, received its charter of incorporation. Philadelphia was threatened by French and Spanish privateers. So, Franklin and other created a volunteer group for defense and built two batteries. Benjamin Franklin recruited militias during the beginning of the French and Indian War from 1754. This war was part of the Seven Years’ War. Many refugees from the western frontier came into Philadelphia during that war. Pontiac’s Rebellion happened in 1763 which was about Native Americans fighting against Western occupation. During that time, refugees again fled into the city. Some of these refugees were a group of Lenape hiding from other Native Americans. They were angry at pacifism and white frontiersmen. The Paxton Boys (or a Scots-Irish frontier vigilante group. This group was a bigoted anti-Native American group. They are widely known for murdering 21 Susquehannock in events collectively called the Conestoga Massacre) tried to follow them or the Native Americans into Philadelphia for attacks, but was prevented by the city's militia and Franklin, who convinced them to leave. At daybreak on December 14, 1763, a vigilante group of the Scots-Irish frontiersmen attacked Conestoga homes at Conestoga Town (near present day Millersville), murdered six, and burned their cabins. Following attacks on the Conestoga, in January 1764 about 250 Paxton Boys marched to Philadelphia to present their grievances to the legislature. Met by leaders in Germantown, they agreed to disperse on the promise by Benjamin Franklin that their issues would be considered. Many people back then oppose the murderous acts of the Paxton Boys.

Philadelphia during the American Revolution

By the 1760’s, the British Parliament’s passage of the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts (along with other frustrations) caused increased political tension and anger against England in the colonies. Philadelphia residents joined the boycotts of British goods. After the Tea Act in 1773, there were threats against anyone who would store tea and any ships that brought tea up the Delaware. After the Boston Tea Party, a shipment of tea arrived in December. It was on the ship called the “Polly.” A committee told the captain to depart without unloading his cargo. There were a series of acts in 1774, which angered the colonies. Therefore, activists called for a general congress and they agreed to meet in Philadelphia. The First Continental Congress was held in September in Carpenters’ Hall. After the American Revolutionary War started in April 1775 (after the Battles of Lexington and Concord), the Second Continental Congress met in May at the Pennsylvania State House. At that location, they also met a year later to write and sign the Declaration of Independence in July of 1776. Philadelphia was a vital city in the war effort. According to Robert Morris, he said that:

“…You will consider Philadelphia, from its centrical situation, the extent of its commerce, the number of its artificers, manufactures and other circumstances, to be to the United States what the heart is to the human body in circulating the blood…” (Weigley, RF et al. (eds): (1982), Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-01610-2).

The port city of Philadelphia was vulnerable to attack by the British by sea. Officials have recruited soldiers and studied defense for invasion from the Delaware Bay, but they built no forts or other installations. In March of 1776, two British frigates (or a type of warship) began a blockade of the mouth of Delaware Baby. British soldiers were moving south through New Jersey and from New York. In December of 1776, there was the fear of invasion caused half the population to flee the city including the Continental Congress. They moved heavily into Baltimore. General George Washington pushed back the British advance at the battles of Princeton and Trenton. Later, the refugees and Congress returned. In September 1777, the British invaded Philadelphia from the south. Washington intercepted them at the Battle of Brandywine, but they were driven back. Thousands of people fled north into Pennsylvania and east into New Jersey. Congress moved to Lancaster, then to York. British troops marched into the half empty Philadelphia on September 23 to cheering Loyalist crowds. The occupation of Philadelphia by the British lasted for ten months. After the French entered the war on the side of the Continentals, the last British troops pulled out of Philadelphia on June 18, 1778 to help defend New York City. Contentials arrived the same day and reoccupied the city supervised by Major General Benedict Arnold, who had appointed the city’s military commander. The city government was returned a week later and the Continental Congress returned in early July.

The historian Gary B. Nash mentioned about the role of the working class and their distrust of oligarchs in the northern ports. He believes that the working class artisans and skilled craftsmen made up a radical element in Philadelphia that took control of the city started in about 1770. These workers promoted a radical democratic form of government during the revolution. They held power for a while. They also used their control of the local militia to disseminate their ideology to the working class. They stayed in power until the businessmen staged a conservative counterrevolution. Philadelphia suffered serious inflation, causing problems especially for the poor, who were unable to buy needed goods. This led to unrest in 1779, with people blaming the upper class and Loyalists. A riot in January by sailors striking for higher wages ended up with their attacking and dismantling ships. In the Fort Wilson Riot of October 4, men attacked James Wilson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who was accused of being a Loyalist sympathizer. Soldiers broke up the riot, but five people died and 17 were injured.

After the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, the United States Congress moved out of Philadelphia and settled in New York City. NYC was once the temporary capital. Besides the Constitutional Convention in May 1787, United States politics was not centered only in Philadelphia. As a product of a political compromise, Congress chose a permanent capital to be built along the Potomac River (which will be Washington, D.C.). Philadelphia was selected as the temporary United States capital for 10 year starting in 1790. Congress occupied the Philadelphia County Courthouse, which became known as Congress Hall, and the Supreme Court worked at City Hall. Robert Morris donated his home at 6th and Market Street as the residence for President Washington, or the President’s House (in Philadelphia). After 1787, the city’s economy grew rapidly during the post war years. Serious yellow fever outbreaks in the 1790’s interrupted development. Benjamin Rush identified an outbreak in August 1793 as a yellow fever epidemic. That was its first in 30 years and it lasted for four months. 2,000 refugees from Saint-Domingue had recently arrived in the city in flight from the Haitian Revolution. They represented five percent of the city's total population. Some believe that they carried the disease from the island where it as endemic. It was rapidly transmitted by mosquito bites to other residents. The fear of contracting the disease caused 20,000 residents to flee the city by mid-September. Some neighboring towns prohibited their entry. Trade virtually stopped; Baltimore and New York quarantined people and goods from Philadelphia. People feared entering the city or interacting with its residents. The fever finally abated at the end of October with the onset of colder weather and was declared at an end by mid-November. The death toll was 4,000 to 5,000, in a population of 50,000. Yellow fever outbreaks recurred in Philadelphia and other major ports through the nineteenth century. None had the many fatalities as that of 1793. The 1798 epidemic in Philadelphia also promoted an exodus, which had an estimated 1,292 residents died.

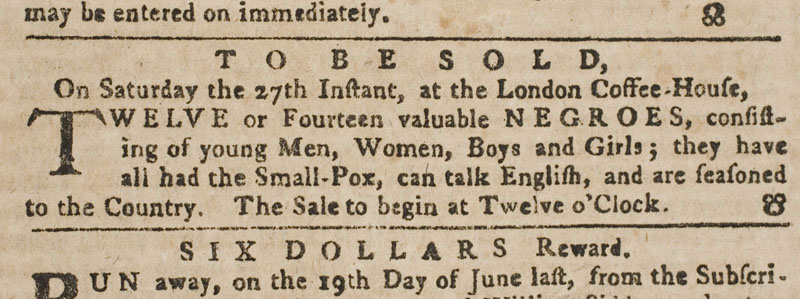

During the 17th century, Sweden colonists owned black African slaves. In 1664, the Delaware settlers contracted the West India Company "to transport hither a lot of Negroes for agricultural purposes." During the 1600’s, black slaves were in Philadelphia and throughout Pennsylvania. Even William Penn and many Quakers back then owned slaves. Penn used slaves to work on his estate called Pennsbury. Slavery is totally evil. The early population of black people in Philadelphia grew in the 1600’s and during the 1700’s. Except for the cargo of 150 slaves aboard the "Bristol" (1684), most black importation was a matter of small lots brought up from Barbados and Jamaica by local merchants who traded with the sugar islands. Prominent Philadelphia Quaker families like the Carpenters, Dickinsons, Norrises, and Claypooles brought slaves to the colony in this way. By 1700, one in 10 Philadelphians owned slaves. Slaves were used in the manufacturing sector, notably the iron works, and in shipbuilding. Indentured servants worked in Pennsylvania as well. 11,000 slaves were in Pennsylvania by 1754 from 5,000 in 1721. Even free black people in Pennsylvania were tried in special courts without a jury during the 1700’s. Pennsylvania Mennonites had expressed concerns about slavery since the 17th century, but it was only in 1758 that Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends made buying or selling a slave a bar to leadership in the Quaker meetings. In 1774 it became cause for disowning. Pennsylvania started to abolish slavery in 1780. The state required any slaves brought to the city to be freed after six months’ residency. This law was not a pure proclamation of emancipation as about 6,000+ slaves were in Pennsylvania. The act that abolished slavery in Pennsylvania freed no slaves outright, and relics of slavery may have lingered in the state almost until the Civil War. There were 795 slaves in Pennsylvania in 1810, 211 in 1820, 403 or 386 (the count was disputed) in 1830, and 64 in 1840. By 1860, no slaves existed in Pennsylvania. The state law was challenged by French colonial refugees from Saint-Domingue. These refugees brought slaves with them. These slaves were defended by the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Through 1796, 500 slaves from Saint-Domingue gained freedom in the city. Because of the violence accompanying the revolution on the island, Philadelphians, many of whom had southern ties, and residents of the Upper South worried that free people of color would encourage slave insurrections in the U.S. During the city’s 10 years as federal capital, members of Congress were exempt from the abolition law, but many slaveholders in the executive and judicial branches were not. President Washington, Vice-president Jefferson and others brought slaves as domestic servants, and evaded the law by regularly shifting their slaves out of the city before the 6-month deadline. Two of Washington's slaves escaped from the President's House (Philadelphia), and he gradually replaced his slaves with German immigrants who were indentured servants. The remains of the President’s House (in Philadelphia) were found during excavation for a new Liberty Bell Center. This led to the archaeological work in 2007. In 2010, a memorial on the site open-ended to remember Washington’s slaves and African Americans in Philadelphia and U.S. history (as well to mark the house site).

Mother Bethel sits on the oldest plot of land continuously owned by African Americans in the United States. James Forten was a wealthy black American sailmaker. He employed a multiracial group of craftsmen. He was a leader of the African American community in Philadelphia and supporter of reform causes. The American Antislavery Society was organized in his house in 1833. He lived from 1766 to 1842. Pennsylvania Hall at 6th & Race was built as a safe haven for abolitionists. It was burned to the ground just 3 days after it opened. Yet, the movement for justice continued. Robert Purvis also fought for abolitionism too. He lectured and wrote literature. He was part of the Underground Railroad by building a secret area at his house to hide slaves. Philadelphia was a known city where slaves traveled into before many of them came into other areas of the North including Canada. William Still was part of the anti-slavery movement too. One famous Underground Railroad stop was Johnson House in Germantown. One of the greatest Sisters of the abolitionist movement was Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. She was an African American abolitionist, suffragist, poet, and author. She was born in Baltimore and she worked in Philadelphia as well. She helped escaped slaves to have freedom on their way into Canada via the Underground Railroad. She was a public speaker and a political activist. She joined the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1853. Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects (1854) became her biggest commercial success. Her short story "Two Offers" was published in the Anglo-African in 1859. She published Sketches of Southern Life in 1872. It detailed her experience touring the South and meeting newly freed Black people. In these poems she described the harsh living conditions of many human beings. After the Civil War she continued to fight for the rights of women, African Americans, and many other social causes. In 1858, she refused to give up her seat or ride in the “colored” section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia (100 years before Rosa Parks) and wrote one of her most famous poems, “Bury Me In A Free Land,” when she got very sick while on a lecturing tour. Her short story “The Two Offers” became the first short story to be published by a Black woman.

"We want more soul, a higher cultivation of all spiritual faculties. We need more unselfishness, earnestness, and integrity. We need men and women whose hearts are the homes of high and lofty enthusiasm and a noble devotion to the cause of emancipation, who are ready and willing to lay time, talent, and money on the altar of universal freedom."

-Sister Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

In 1866, Harper gave a moving speech before the National Women's Rights Convention, demanding equal rights for all, including Black women. During the Reconstruction Era, she worked in the South to review and report on living conditions of freedmen. This experience inspired her poems published in Sketches Of Southern Life (1872). She used the figure of an ex-slave, called Aunt Chloe, as a narrator in several of these. She passed away in February 22, 1911. Caroline Le Count was in support of the desegregation of the city’s horse-drawn streetcars. She was called a slur by a conductor and the conducted was fined $100. Octavius Catto was a black man who was one of the greatest black leaders of the 19th century. He fought on the Union side during the Civil War. He was a fighter for black human rights and supported black people the right to vote. He was a black educator and a civil rights activist in Philadelphia. He became known as a top cricket and baseball player during 19th-century Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In November 1864, Catto was elected to be the Corresponding Secretary of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League. He also served as Vice President of the State Convention of Colored People held in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in February 1865. Catto fought fearlessly for the desegregation of Philadelphia’s trolley car system via civil disobedience. A meeting of the Union League of Philadelphia was held in Sansom Street Hall on Thursday, June 21, 1866, to protest and denounce the forcible ejection of several black women from Philadelphia's street cars. He was a martyr who died to fight for human rights (he was murdered by a racist white man named Frank Kelly, who was Irish. Many racist Irish folks wanted to prevent black people to vote in Philadelphia back then). On October 10, 2007, the 136th anniversary of Cato’s death, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund erected a headstone at Catto's burial site at Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania. On October 10, 2007, the 136th anniversary of Catto's death, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund erected a headstone at Catto's burial site at Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.

Industrial Growth

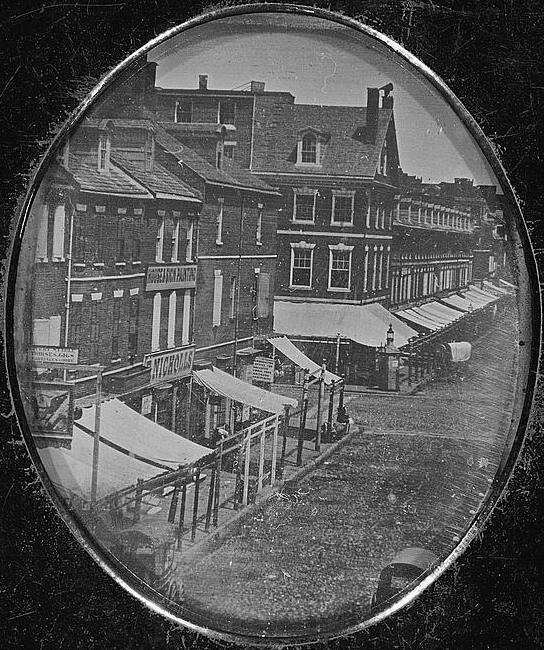

Industrial growth grew in Philadelphia into another level by the 19th century. The Pennsylvania state government left Philadelphia in 1799. The United States government left in 1800. During this time, the city was one of America’s busiest ports and the country’s largest city with 67,787 people living in Philadelphia and its contiguous suburbs. Philadelphia maritime trade was interrupted by the Embargo Act of 1807 and then the War of 1812 (where the British and Americans fought each other). After the war, Philadelphia’s shipping industry never returned to its pre-embargo status. New York City succeeded it as the busiest port and the largest city in America. The embargo and decrease in foreign trade led to the development of local factories. These factories produced goods no longer available as imports. Manufacturing plants and foundries were built and then Philadelphia existed as an important center of paper related industries (like the leather, shoe, and boot industries). Coal and iron mines and the construction of new roads, canals, and railroads helped Philadelphia’s manufacturing power. The city became the United States’ first major industrial city. Some of the major industrial projects were like waterworks, iron water pipes, a gasworks, and the U.S. Naval Yard. Many workers were exploited economically. So, about 20,000 Philadelphia workers staged the first general strike in North America in 1832. They wanted to end exploitative working conditions. These workers won the ten hour workday and an increase in wages. In addition to its industrial power, Philadelphia was the financial center of the country. Along with chartered and private banks, the city was the home of the First and Second Banks of the United States, Mechanics National Bank and the first U.S. Mint Cultural institutions, such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Athenaeum and the Franklin Institute also developed in the nineteenth century. The Pennsylvania General Assembly passed the Free School Law of 1834 to create the public school system.

In the mid and later 1840’s, immigrants from Ireland and Germany came into the city. This increased the population of Philadelphia and its suburbs. In Philadelphia, as the rich moved west of 7th Street, the poor moved into the upper class’ former homes. These homes were converted into tenements and boarding houses. Many small row houses crowded alleyways and small streets. Some of these areas were filled with garbage and the smell of manure from animal pens. During the 1840's and 1850's, hundreds died each year in Philadelphia and the surrounding districts from diseases such as malaria, smallpox, tuberculosis, and cholera, related to poor sanitation and diseases brought by many factors. The poor suffered the most fatalities. Small row houses and tenement housing were constructed south of South Street. There were issues of violence too. Gangs like the Moyamesning Killers and the Blood Tubs controlled various neighborhoods. During the 1840's and early 1850's when volunteer fire companies, some of which were infiltrated by gangs, responded to a fire, fights with other fire companies often broke out. The lawlessness among fire companies virtually ended in 1853 and 1854 when the city took more control over their operations. During the 1840's and 50's, violence was directed against immigrants by people who feared their competition for jobs and resented newcomers of different religions and ethnicities. The evil of xenophobia is not a new phenomenon in American society. The Gangs of New York film outlined these tensions which were common in Northeastern and Midwestern cities back then. Nativists were bigots and their views are similar to the Tea Party. Many of them were anti-Irish and some didn’t like Catholics. Violence against immigrants occurred constantly. The worst in the Philadelphia was the nativist riots in 1844. Also, violence against African Americans was also common during the 1830's, 40's, and 50's. Immigrants competed with them for jobs, and deadly race riots resulted in the burning of African-American homes and churches by cowardly racists. In 1841, Joseph Sturge commented "...there is probably no city in the known world where dislike, amounting to the hatred of the coloured population, prevails more than in the city of brotherly love!" Several anti-slavery societies had been formed and free blacks, Quakers and other abolitionists operated safe houses associated with the Underground Railroad, but many working class and many ethnic whites opposed the abolitionist movement.

The Civil War

Philadelphia during the Civil War in America was a place where many troops, money, weapons, medical care, and supplies aided the Union. Before the Civil War happened, Philadelphia had economic connections with the South made much of the city sympathetic to South’s grievances with the North. It was America’s second largest city during the antebellum period. This fostered political sympathy; for example, political leaders in the city called for the repeal of laws that might be considered unfriendly to South. Meetings led to calls for Pennsylvania to decide which side the state was on in the case of Southern succession. Many abolitionists were harassed and threatened in Philadelphia. In the 1860 mayoral election the Democratic Party candidate John Robbins challenged People's Party candidate and incumbent mayor Alexander Henry. The People's Party in Pennsylvania was aligned with the national Republican Party, but downplayed the issue of slavery and made tariff protection their main issue in the state. During the election, the Democrats attacked Alexander Henry's moderate position on slavery as virtual abolitionism. Alexander Henry was reelected. Abraham Lincoln won the city by 52 percent of the city’s vote.

Once the Civil war started, many Philadelphians’’ opinion shifted in support for the Union and the war against the Confederates. American flags and bunting existed all over the city as people were angry at southern sympathizers. A mob threatened the home of the Palmetto Flag, a secessionist newspaper. The police and Mayor Alexander Henry were able to prevent the mob from causing damage, but the newspaper shutdown shortly after. Other newspapers which also had a pro-southern slant also suffered from dwindling circulation. Around August 1861 federal authorities arrested eight people for expressing pro-southern sympathies. Most of the people were released soon after, but one, the son of William H. Winder, was held for more than a year. Authorities also shut down a pro-southern weekly newspaper called the Christian Observer.

More than 50 infantry and cavalry regiments were recruited fully or in part in Philadelphia. The city was the main source for uniforms for the Union Army. The city manufactured weapons and built warships. Two of the largest military hospitals in America during that time were in Philadelphia. Their names are Satterlee Hospital and Mower Hospital. By 1863, Philadelphia was threatened by Confederate invasion during the Gettysburg Campaign. Major-General Napoleon Jackson Tecumseh Dana took command of the military district of Philadelphia on June 26. With Mayor Henry finding volunteers Dana organized the construction of entrenchments to defend the city. Pennsylvania governor Andrew Gregg Curtin arrived in the city at the beginning of July hoping to rally the city out its lack of urgency. Philadelphia’s 20th Pennsylvania Emergency Regiment and First City Troop were among the militia involved with preventing the Confederate crossing the Susquehanna River at Wrightsville, by burning the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge. Yet, the Confederate Army was turned back at Wrightsville, Pennsylvania and at the Battle of Gettysburg. After Gettysburg, support for the war increased. Vicksburg was a victory for the Union and patriotic feelings grew. More people enlisted in the army. Philadelphia voted for the reelection of Republican Governor Curtin over Peace Democrat George Washington Woodward. The Civil War caused Philadelphia to witness the rise of the Republican Party. The draft in the city existed in 1863.

In June 1864, the Philadelphia division of the United States Sanitary Commission organized a large fair to raise money to buy bandages and medicine. The Great Central Fair lasted two weeks, and was held in temporary buildings covering several acres of Logan Square. Thousands of works of art were lent for display, many donated for auction. Among the visitors was President Lincoln. The Sanitary Fair raised $1,046,859. In the 1864 election, the majority of Philadelphians voted to reelect President Abraham Lincoln and the four congressmen from Philadelphia. The National Union Party also gained majority in both houses of the Philadelphia City Council. In December 1864, Philadelphia streetcar companies started to allow African Americans on the streetcars or running streetcars specifically for African Americans. The city’s streetcars were not fully integrated until 1867 when the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed a law requiring it. Many soldiers from New England and New Jersey came through Philadelphia heading south. Local residents formed two organizations, the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon and the Cooper Shop Refreshment Saloon, to greet arriving soldiers with refreshments and letter-writing materials. The Washington Grays was the first Philadelphia regiment sent out of the city being a volunteer formation. It was dispatched to help defend Washington, D.C.. The unit made it to Baltimore, Maryland, where it was attacked by a secessionist mob in the Baltimore riot of 1861. The brigade retreated to Philadelphia, where George Leisenring, a German-born private, died, becoming Philadelphia's first war casualty. The first Philadelphians to encounter Confederate forces were the Twenty-third Infantry Regiment and the First City Troop at the Battle of Hoke's Run in West Virginia. More than 50 infantry and cavalry regiments were eventually recruited fully or in part in Philadelphia. These included the Philadelphia Brigade and the 118th Pennsylvania Infantry, recruited and sponsored by the Philadelphia. In addition, 11 United States Colored Troops were organized in Philadelphia. During the war, between 89,000 and 90,000 Philadelphians were on enlistment rolls. This number includes reenlistments and does not include African American soldiers from Philadelphia, whose enlistment numbers are unknown. The Civil War library and Museum, which is now the Civil War Museum of Philadelphia was founded in 18898. The oldest chartered American Civil War institution or the civil War and Underground Railroad Museum of Philadelphia was founded by the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United State. It collects records, artifacts, and other items related to the American Civil War and the Underground Railroad. Philadelphia's largest Civil War monument is the Smith Memorial Arch, built on the former grounds of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in West Fairmount Park. Designed by James H. Windrim, and completed in 1912, it includes sculptures by Herbert Adams, George Bissell, Alexander Stirling Calder, Daniel Chester French, Charles Grafly, Samuel Murray, Edward Clark Potter, John Massey Rhind, Bessie Potter Vonnoh, and John Quincy Adams Ward. Philadelphia’s Major General George G. Meade had success from the Battle of Gettysburg and was commander of the Army of the Potomac. Philadelphia celebrated returning war heroes and Civil War veterans with parades. On June 10, 1865 the city held a grand review with Meade leading veteran soldiers through the city in to a dinner at a volunteer refreshment saloon. Another grand review of Civil War veterans was held as part of the Independence celebration in 1866. This parade was led by another Philadelphian war hero, Winfield Scott Hancock. 44 soldiers and sailors from Philadelphia received the Medal of Honor. They include Sergeant Richard Binder, Captain Henry H. Bingham, Captain John Gregory Bourke, Captain Cecil Clay, etc.

The Republicans back then had many anti-slavery leaders and it created a political chance to dominate Philadelphia politics for almost a century.

The late 19th century

After the Civil War, Philadelphia’s population continued to grow. Its population increased from 565,529 in 1860 to 674,022 in 1870. The city’s population stood at 817,000 in 1876. The dense population areas were not only growing north and south along the Delaware River. They were also moving westward across the Schuylkill River. Much of the growth came from the immigrants. They were still mostly Irish and German back then. In 1870, 27 percent of Philadelphia’s population was born outside the United States. By February 1854, there was the Act of Consolidation. That made the city of Philadelphia inclusive of the entire county, doing away with all other municipalities. By the 1880’s, immigration from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Italy started to rival the immigration from Western Europe. Many of the immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe were Jewish. In 1881, there were about 5,000 Jewish people in Philadelphia. By 1905, the Jewish population increased to 100,000 people. Philadelphia’s Italian population grew from about 300 in 1870 to about 18,000 in 1900. The majority of the Italians settled in South Philadelphia back then. There was strong foreign immigration. Also, there was domestic migration of African Americans from the South. This caused Philadelphia to have the largest black population of a Northern U.S. city during this period. By 1876, nearly 25,000 African Americans living in Philadelphia and by 1890 the population was near 40,000. Immigrants moved into the city. Philadelphia’ rich left the city for newer housing in the suburbs. They made commuting easy with the newly constructed railroads. During the 1880’s, much of Philadelphia’ upper class moved into the growing suburbs along the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Main Line west of the city. The city was dominated by the Republican Party politically. There was still voter fraud and intimidation. The Gas Trust was the hub of the city’s political machine. The trust controlled the gas company. It supplied lighting to the city;. The board was under complete control by the Republicans in 1865. The company gave contracts and perks for themselves and their cronies. Some government reform took place during this time. The police department was reorganized and volunteer fire companies were eliminated and replaced by a paid fire department.

A compulsory school act was passed in 1885 and the Public School Reorganization Act freed the city’s education form the polictical machine. Higher education was changed too. The University of Pennsylvania moved to West Philadelphia and reorganized to its modern form; and Temple University, Drexel University and the Free Library were founded.

Later, the city’s major product was the creation of the Centennial Exposition. That was the first World’s Fair in America which celebrated the nation’s Centennial. It was held in Fairmount Park. It show exhibitions like Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone and the Corliss Steam Engine. It started in May 10, 1876 and the Exposition ended on November 10. During that time period, more than 9 million people had visited the fair. The city undertook a construction of a new city hall. It was created to match its ambitions. The project was graft-ridden and it took twenty-three years to complete. At completion in 1884, City Hall was the tallest building in Philadelphia, a position it maintained for nearly 100 years. During that time period, Philadelphia’ industries included the Baldwin Locomotive Works,William Cramp and Sons Ship and Engine Building Company, and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Westward expansion of the Pennsylvania Railroad helped Philadelphia keep up with nearby New York City in domestic commerce, as both cities fought for dominance in transporting iron and coal resources from Pennsylvania. Philadelphia's other local railroad was the Reading Railroad, but after a series of bankruptcies, it was taken over by New Yorkers. The Panic of 1873, which occurred when the New York City branch of the Philadelphia bank Jay Cooke and Company failed, and another panic in the 1890s hampered Philadelphia's economic growth. Depressions hurt the city. Its diverse array of industries helped to weather difficult times. It had numerous iron and steel-related manufacturers, including Philadelphian-owned iron and steel works outside the city, most notably the Bethlehem Iron Company in the city by that name. The largest industry in Philadelphia was textiles. Philadelphia produced more textiles than any other U.S. city; in 1904 the textile industry employed more than 35 percent of the city's workers. The cigar, sugar, and oil industries also were strong in the city. During this time the major department stores: Wanamaker's, Gimbels, Strawbridge and Clothier, and Lit Brothers, were developed along Market Street.

By the end of the century, the city provided nine municipal swimming pools, making it a leader in the nation.

Early 20th Century

During the start of the 20th century, Philadelphia had gone through changes. There was political corruption in the city. The Republican controlled political machine was controlled by Israel Durham. The machine dominated the city government. One official estimated that US$5 million was wasted each year from graft in the city’s infrastructure programs. The majority of the residents in Philadelphia back then were Republicans. Yet, voter fraud and bribery were still common. The city enacted election reforms in 1905 like personal voter registration and the establishing of primaries for all city offices. Many residents became complacent. The city’s political bosses continued in control. After 1907, Durham retired. His successor was James McNichol. He never controlled much of the city outside of North Philadelphia. In South Philadelphia, the Vare brothers (George, Edwin, and William) created their own organization. With no central authority, Senator Boies Penrose took charge. In 1910, infighting between McNichol and the Vares contributed to the reform candidate, Rudolph Blankenburg, to be elected mayor. During his administration, he made numerous cost-cutting measures and improvements to city services, but he served only one term. The machine again gained control. The policies of Woodrow Wilson’s administration reunited reformers with the city’s Republican Party and World War I temporarily halted the reform movement. In 1917, the murder of George Eppley, a police officer defending City Council primary candidate James Carey, ignited the reformers again. They passed legislation to reduce the City Council from two houses to one and provided council members on annual salary. With the deaths of McNichol in 1917 and Penrose in 1921, William Vare became the city’s political boss. In the 1920’s, the public flouting of Prohibition laws, mob violence, and police involvement in illegal activities led Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick to appoint Brigadier General Smedley Butler of the U.S. Marine Corps as director of public safety.

Butler cracked down on bars and speakeasies and tried to stop corruption within the police force, but demand for liquor and political pressure made the job difficult, and he had little success. After two years, Butler left in January 1926 and most of his police reforms were repealed. On August 1, 1928, Boss Vare suffered a stroke, and two weeks later a grand jury investigation into the city's mob violence and other crimes began. Many police officers were dismissed or arrested as a result of the investigation, but no permanent change resulted. There was strong support among some residents for the Democratic Presidential candidate Al Smith (who was Catholic), which marked the city’s turning away in the 20th century from the Republican Party. Also, immigrants increasingly came into Philadelphia from Eastern Europe, and Italy. African Americans migrated from the South to Philadelphia too. There was World War I which briefly interrupted foreign immigration. There was demand for labor for the city’s factories. One factory is U.S. Naval Yard at Hog Island, which constructed ships, trains, and other items needed during the war effort. This helped to attract blacks in the Great Migration of African Americans. By September 1918, there were cases of influenza pandemic. This was reported at the Naval Yard and it began to spread. Mortality on some days was several hundred people and, by the time the pandemic began to subside in October, more than 12,000 people had died. There has been the rising popularity of automobiles led to widening of roads and the creation of Northeast (Roosevelt) Boulevard in 1914. The Benjamin Franklin Parkway was developed in 1918. There were many changes to many existing streets to one way streets in the early 1920’s along with the construction of the Delaware River (Benjamin Franklin) Bridge to New Jersey in 1926. Philadelphia began to modernize, steel and concrete skyscrapers were constructed, old buildings were wired for electricity, and the city's first commercial radio station was founded. In 1907 the city constructed the first subway. It hosted the Sesqui-Centennial Exposition in South Philadelphia, and in 1928 the city opened the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Great Depression and World War II

The Great Depression (which was caused by bad policies from many large banking interests) harmed America greatly. In the three years after the stock market crashed in 1959, 50 Philadelphia banks closed. Of those, only two were large which were: Albert M. Greenfield’s Bankers Trust Company and Franklin Trust Company. Savings and loans associations also faced trouble. They had trouble with mortgages of 19,000 properties being foreclosed in 1932 alone. By 1934, 1,600 of 3,400 savings and loans associations had shut down. Regional manufacturing fell by 45 percent from 1929 to 1933. In the same time, factory payrolls fell by 60 percent, retail sales fell by 40 percent and construction had it payrolls fell by 84 percent. Unemployment peaked in 1933 when 11.5 percent of whites, 16.2 of African Americans, and 10.1 percent of foreign born whites were out of work. Mayor J. Hampton Moore was wrong to blame people’s economic woes not on the worldwide Great Depression, but on laziness and wastefulness, and claimed there was no starvation in the city. Soon, he fired 3,000 city workers, instituted pay cuts, forced unpaid vacation, and reduced the number of contracts that the city awarded. These actions were unpopular with the unemployed. The city prevented defaulting on its debts and people say that millions of dollars were saved. The city relied on state money to fund relief efforts. Moore's successor S. Davis Wilson instituted numerous programs financed by Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal's Works Progress Administration, despite condemning the program during his mayoral campaign. At the peak of WPA-financed jobs in 1936, 40,000 Philadelphians were employed under the program. Encouragement from the state government and labor’s founding of the CIO (or the Congress of Industrial Organizations), Philadelphia became a union city. Many trade unions used discrimination against African Americans for years and they were closed out of some labor advances. There has been workers’ dissatisfaction with conditions led to numerous strikes in the textile unions, and the CIO organized labor in other industries, with more strikes taking place. During the 1930’s, the Democratic Party began to grow in Philadelphia. This has been influenced by the leadership of the Roosevelt administration during the Depression. A newly organized Independent Democratic Committee reached out to residents. In 1936, the Democratic National Convention was helped in Philadelphia. The majority of voters in the city reelected the Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt as President. They also voted for Democratic Congressmen and state representatives. City government continued to be dominated by Republicans, but the politicians were elected by small margins. The beginning of World War II in Europe and the attack on Pearl Harbor caused the U.S. to be more involved in generating new jobs in defense related industries. After the U.S. became involved in the war in 1941, the city mobilized. Philadelphia has consistently met war bond quotas and when the war ended in 1945. 183,850 residents were in the U.S. armed forces. With so many men serving in the military, there had been a labor shortage; businesses and industries hired women and workers from outside the city. In 1944 the Company promoted African Americans to positions as motormen and conductors (from which they had previously been excluded) on public transportation vehicles. Resentful, other PTC workers protested and began a strike that nearly immobilized the city. President Roosevelt sent troops to replace the striking workers. After a federal ultimatum, the workers returned after six days. This was the time when African Americans were fighting for their economic rights.

After World War II ended, Philadelphia had a serious housing stortage. About half of the city’s housing had been built in the 19th century. Many units lacked proper sanitary facilities, were overcrowded, and in poor condition. There was the growth of competition for housing. African Americans (many of whom had come into the city from the Great Migration of the South) and Puerto Ricans moved into new neighborhoods. This caused some racial tension. The wealthier middle class residents (many of them were white) continued to move out to the suburbs which would later be called white flight. Phialdelphia’s population peaked at more than two million people in 1950. Afterwards, the city’s population declined while that of the neighboring suburban counties grew. Some residents moved out of the region completely, because of the restructuring of industry and the loss of tens of thousands of jobs in the city. Philadelphia lost five percent of its population in the 1950s, three percent in the 1960s and more than thirteen percent in the 1970s. Manufacturing and other major Philadelphia businesses, which had supported middle-class lives for the working class, were moving out of the area or shutting down in industrial restructuring, including major declines in railroads. The city encouraged development projects. One was the University City in West Philadelphia and the area around Temple University in North Philadelphia. It removed the “Chinese Wall” elevated railway, and developed Market Street East around the transportation hub. Some gentrification occurred with the restoration of properties in historic neighbhorhoods like Society Hill, Rittenhouse Square, Queen Village, and the Fairmount area. The airport expanded, the Schukylkill Expressway and the Delaware Expressway (Interstate 95) was built. During this time, SEPTA was created and residential and industrial development took place in Northeast Philadelphia. Preparations for the United States Bicentennial in 1976 began in 1964. By the early 1970’s, US$3 million had been spent but no plans were set. The planning group was reorganized and numerous city wide events were planned. Independence National Historical Park was restored and development of Penn’s Landing was completed. Less than half the expected visitors came to the for the Bicentennial, but the city helped to revive the identity of the city. It inspired annual neighbhorhood events and fairs.

In 1947, Richardson Dilworth was selected as the Democratic candidate, but lost to incumbent mayor Bernard Samuel. Durign the campaign Dilwoth made numerous specific charges about corruption within city government. The City Council set up a committee to investigate. Their findings followed by a grand jury investigation. The five-year investigation and its findings garnered national attention. US$40 million in city spending was found to be unaccounted for, and the president judge of the Court of Common pleas had been tampering with court cases. The fire marshal went to prison; and an official in the tax collection office, a water department employee, a plumbing inspector, and head of the police vice squad each committed suicide after criminal exposures. The public and the press demanded reform. Later, the new charter strengthened the position of the mayor and weakened the City Council. The Council would be made of ten councilmen elected by district and seven at large. City administration was streamlined and new boards and commissions were created. Joseph S. Clark in 1951 was elected as the first Demcoratic mayor in 80 years. Clark filled the administration positions based on merit and worked to weed out corruption. Despite reforms and the Clark administration, a powerful Democratic patronage organization eventually replaced the old Republican one. Clark was succeeded by Richardson Dilworth. Dilworth continued the policies of his predecessor. Dilworth resigned to run for governor in 1962. The city council President James H. J. Tate was elected as the city’s first Irish Catholic mayor. Tate was elected mayor in 1963 and releelcted in 1967 despite opposition from reformers who opposed him as an organization insider. In Philadelphia, and in other large U.S. cities, the 1960’s was a turbulent decade for the city. Numerous civil rights and anti-war protests took place. There were large protests led by Marie Hicks to desegregate Girard College. Students took over the Community College of Philadelphia in a sit-in. Race riots broke out in Holmesburg Prison and in 1964 riot along West Columbia Avenue, which killed 2 people (it injured over 300 people and caused US$3 million in damages). In 1967, the Temple University’s Urban Archives (of Philadelphia) was created. Also, the Philadelphia Flyers NHL team was founded too in 1967.

The Civil Rights Movement of Philadelphia

A lot of people don’t know about the civil rights movement of the North. To be honest, some of the following information is the first time that I knew of these events in my life (in 2016). Civil rights wasn’t just a Southern issue. It was a national issue and many unsung heroes in Philadelphia fought for equal rights and human justice. The sacrifice of men, women, and children in Birmingham, Alabama, who stood up against apartheid & oppression, was heroic. We know about Selma when courageous black people and white people stood up against racist mobs, racist Sheriffs, and many obstacles to achieve the Voting Rights Act. Their sacrifice will always be honored and remembered. Now, it is the time to show information about the Civil Rights movement in Philadelphia.

During the 1910’s, the Great Migration began. This was a mass exodus of African Americans from the South into the North, the Midwest, and the West Coast. These Brothers and Sisters wanted to escape Jim Crow oppression and seek better economic and political opportunities. The Black Southerners wanted freedom. Yet, the more things change, the more that they stayed the same. In the North like in Philadelphia, there was less legalized segregation than in the Deep South. Yet, racism existed in jobs and other areas. Segregation even existed in Philadelphia during the 20th century too. It existed in Philadelphia in hotels, restaurants, workplaces, trade unions, residential neighbors, and even schools. People successfully desegregated Philadelphia’s street cars during the 1860’s. The NAACP or the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People founded its local Philadelphia chapter in 1912. The Philadelphia NAACP back then fought for the rights of black migrants coming into Philadelphia. World War I soon existed and reactionary quota immigration laws were passed (that heavily restricted European immigration into America). This caused massive black migrants from the South to come into Philadelphia. By 1920, Philadelphia’s black population had grown to 134,220, a fifty percent increase from ten years earlier. For the migrants, Philadelphia offered not just employment opportunities unavailable in the South, but also freedom from the daily humiliations of Jim Crow segregation. Racial discrimination still persisted in Philadelphia though. During 1917 and 1918, white racists attacked and murdered many black people in Philadelphia. The violence in 1919 was called Red Summer, because of the massive bloodshed in the streets of America (as a product of racial riots). Many black people worked in Northern industrial plants.

After World War I, many black people were pushed out of industrial jobs that they first had. Only 6.1 percent of black workers in Philadelphia were employed in the industrial sector in 1927. More black people still migrated into Philadelphia. During the 1920’s, Philadelphia’s black population grew another 64 percent to 219,599. The Great Depression happened in 1929 into the 1930’s. Black migration into Philly massively declined by then to a trickle. Also, the Philadelphia NAACP worked to fight for civil rights. Civil rights attorneys Raymond Pace Alexander and his wife Sadie T. M. Alexander successfully lobbied the Pennsylvania Legislature to pass legislation to ban racial discrimination in public accommodations n the state. The YPIF or the Young People’s Interracial Fellowship was created to fight for racial dialogue among the city’s white and black congregations. Other organizations fought for racial justice too. In 1937, YPIF evolved into the Fellowship House. This group was an interracial settlement house. They worked in nonviolent training in North Philadelphia. Samuel Evens (in 1936) created the Philadelphia Youth Movement. He migrated from Florida to Philadelphia back in 1920. He created many “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” campaigns along the Columbia Avenue business district in North Philadelphia. By 1937, Philadelphia organized the NNC. This was the National Negro Congress. It was made up of a group of civil rights, labor, religious, and left wing groups. It was headed by the black trade union leader A. Philip Randolph. A. Philip Randolph was a famous democratic socialist and civil rights leader. The Philadelphia chapter of the NNC, under the direction of noted African-American educators and community activists Arthur Huff and Crystal Bird Faust, led protests against employment and housing discrimination and worked to build alliances between the black community and the trade union movement of the 1930's. Unions were key in the economic justice movement. World War II saw the increase of more black people into Philadelphia. There was a demand for labor and defense industries grew. During this time, racial discrimination existed along with new opportunities. Racial discrimination in Philly back during the 1940’s was huge. It dealt with housing, technical services, employment, and professional jobs. Many jobs were closed to black people. The NAACP membership increased to 16,700 in Philadelphia. Also, in 1942, civil rights, civil liberties, and religious groups worked to fight racial and religious bias in the city. There is a photograph displaying African American employees parading in protest of Philadelphia Transit Company at Reyburn Plaza in 1943.

In the 1944 transit strike, the Fellowship Commission and the NAACP worked as one to prevent racial violence in the city. The strike came after wartime advances in civil rights. By June 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802. That banned racial discrimination in defense industries in return for A. Philip Randolph’s agreement to cancel his protest march in Washington, D.C. for racial justice.

Three years later, the Federal Committee on Fair Employment Practices Commission (known as the FEPC) ordered the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) to integrate its workforce of bus and trolley drivers. On August 1, 1944, the company’s white workers responded by organizing a wildcat strike that crippled the city and its vital defense industries for six days. Finally, on August 6, the Secretary of War ordered U.S. Army units into Philadelphia to operate the buses and trolleys. For most black Philadelphians back then, this was the first time within memory that the federal government had taken aggressive action to defend their rights as citizens. After the war, Philadelphia enacted historic civil rights legislation. Southern Congressmen back then blocked progressive civil rights bills on the federal level. So, Northern states and municipalities enacted their own civil rights legislation (in a local and statewide basis) in order to deal with discrimination and racial segregation. The Fellowship Commission and its member organizations achieved their first major victory in 1948. This was when the Republican controlled City Council passed the Fair Employment Practices ordinance. Their other success came 3 years later. Sadie Alexander led the Commission to press for the inclusion of a ban on racial and religious discrimination in municipal employment services and contracts (in the city’s new Home Rule Charters). Voters supported this charter in April 1951. The anti-discrimination provisions also provided for the creation of a new city agency. It was called the Philadelphia Commission was elected to represent North Philadelphia on the City Council on the same Democratic ticket. This ticket allowed the reformer Joseph Clark to be on the Mayor’s office. The Republican machine of 50 years ended.

The population of the seven suburban counties surrounding the city grew by eighty-five percent between 1940 and 1960, while the white population within the city fell by thirteen percent. The black population in Philadelphia grew from 1940 to 1960. Most black people lived in inner city, high density neighborhoods. By 1960, the black population in North Philly was 69 percent from 28% in 1940. The slow pace disappointed civil rights leaders like Rev. Leon Sullivan of the North Philadelphia’s Zion Baptist church. He was part of the local NAACP. So, in 1960, Sullivan created the 400 Ministers group. This was a group of black pastors to oppose discriminatory practices in jobs. Inspired by the Southern student sit-in movement that had begun just four months earlier (in Greensboro, North Carolina), but modeled on the “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” protests of the 1930's, selective patronage called on black Philadelphians to boycott major local retailers, one company at a time, until they agreed to meet the 400 Ministers’ demands for the hiring and promotion of black workers. They boycotted Tastykake Baking Company and met some demands in a matter of 2 moths. Inspired by the Woolworth’s sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, the Philadelphia Youth Committee Against Segregation pickets Woolworth’s stores in neighborhoods with significant black populations in February 1960.

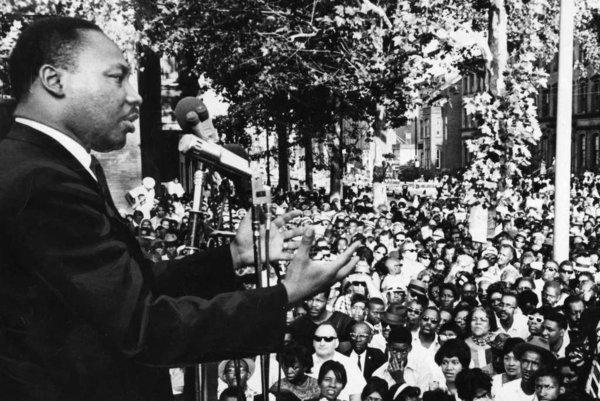

Philadelphia’s NAACP became more militant in 1963. Cecil B. Moore continued to promote the boycott actions. They also wanted black workers to build the Strawberry Mansion junior high school. By May 1963, people agreed to hire five black workers to skilled positions on the Strawberry Mansion site. The Commission on Human Relations and the NAACP wanted more black employment in the skilled trades of Philadelphia. The early 1960’s to mid-1960’s of the civil rights movement was characterized by activism, coalition building, usage of the formal political process, and boycotts. The Columbia Avenue rebellion in August 1964 was a new era of Philadelphia. 1964 saw rebellions in Harlem, Rochester, NYC, and in other cities in America. The rebellion was a response to police brutality, racism, discrimination, and other evil conditions in urban communities of America. The rebellion happened in August 28, 1964 when a false rumor of a pregnant black woman being killed by the Philly police. Later, people primarily young black Philadelphians roamed the streets of North Central Philadelphia, looting white-owned stores and skirmishing with the police. Many people who rebelled the crowds of black North Philadelphians responded to the calls of African-American civil rights and community leaders, including Raymond Pace Alexander, Leon Sullivan and Cecil B. Moore, urging rioters to return to their homes. “We don’t need no Cecil Moore,” one rioter yelled, “We don’t need civil rights. We can take care of ourselves” (Berson, p. 18). The rebellion lasted for 3 days. Soon, the Black Power movement would spread across America. Many Black Power individuals wanted community control, black empowerment, and self-determination. Some rejected integrationalist civil rights reformism. One of the greatest events of the Philadelphia Civil Rights Movement was the integration of Girard College. As early as May 20, 1954, the Philadelphia City Council that Girard College should admit people regardless of race or color. Girard was stern to oppose the decision.

On August 3, 1965, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addressed the demonstrators at Girard College in Philadelphia. On December 16, 1965, a suit challenging Girard College’s admissions policy is filed in U.S. District Court by city and state officials, as well as the mothers of seven African-American boys seeking admission to the school. The next day, picketing ends at Girard College after seven months of protests.

Protests existed just 7 months after the Columbia Avenue 1964 rebellion. Cecil B. Moore was one leader involved in the movement. Girard is found in the heart of black North Philadelphia. The campaign to desegregate Girard College, which peaked with seven months of daily picketing at the college’s ten-foot high walls. A lot of young people were involved in the movement too. It would be until 1968 via a Supreme Court decision when black people would be allowed to go into Girard College. The Girard College trustees voted to admit African-American students to the school on May 23 and on June 24, 1968, an estimated crowd of 600 people attend a victory rally at Girard College.

The Black Power movement in Philadelphia is not well known by a lot of people. Now, we live in a new generation where more of the truth is shown to the public globally. From the late 1960’s to the 1970’s, civil rights activity in Philadelphia was strong. Leon Sullivan used selective patronage campaigns to nonviolently protest injustice. Also, the Black Panther Party existed in Philadelphia as well. The Black Panthers originated in 1966 in Oakland, California. They focused on self-defense, opposing police brutality, embracing Marxist/socialist ideological thinking, and community activism. They or the Panthers came into North Philadelphia (with a high percentage of black residents) to create their organization in Columbia Avenue. The Black Panthers believed in self-defense while Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference believed in proactive, nonviolent resistance against evil. Yet, groups as ideologically diverse as the SCLC, the Black Panthers, and SNCC desired the same goal, which is freedom, justice, and equality for black people. The Panthers advanced the Ten Point Program, which progressively wanted housing, land, bread, clothing, justice, education, and peace. When the Panthers came into Philadelphia, they meet with the Episcopal religious leader Paul Washington. He was the rector of the respected Church of the Advocate. The Church of the Advocate was once mostly white and then it changed under Washington’s leadership. His congregation was found in a Gothic cathedral at the corner of 18th and Diamond Streets. The church would be a major meeting place of Philadelphia’s civil rights and Black Power movements.

In 1968, Church of the Advocate hosted the city’s Black Power Conference, bringing into its sanctuary such civil rights leaders as Rosa Parks, Ron Karenga, LeRoi Jones (Inamu Amiri Baraka), and Jesse Jackson. In 1974, it witnessed the ordination of the Episcopal church’s first 11 female priests. And between 1973 and 1976, it installed on its walls groundbreaking mural artwork depicting the biblical narrative through the lens of African American history. Washington allowed the Black Panthers in Philadelphia to have many events from memorial services of national and local victims of police brutality. Washington met and talked with Reggie Schnell or the defense captain for the group’s Philadelphia chapter. By 1971, the Panthers sent a request that the National Black Panther Party hold its Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in the church’s sanctuary. Washington agreed with the Panthers expressing anger at the system. Yet, he questioned whether using physical force as a way to get equal treatment under the law or enact real social change. He still allowed the Black Panthers to use the places in the church. Soon, additional space was needed as the crowds were bigger. Then, Temple University was used for the Black Panther National Convention in 1971. The FBI illegally monitored and had filed on Washington, the Black Panthers, and their supporters for years. The FBI alerted the U.S. President, Vice-President, Attorney General, the military, and the Secret Service that Temple had agreed to make their large new gymnasium, McGonigle Hall, available for the event. The Bureau would quickly dispatch informants to clandestinely observe and report on the event. There was the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention on September 5, 1970. One famous professor in Temple University of African American Studies is Professor Molefi Asante. After a Philly cop was shot and killed by an African American male, Philadelphia police chief Frank Rizzo overreacted and executed brutal and humiliating raids on the city’s three Panther offices. Panther leaders were jailed. Later, Panther leaders were freed. Eight thousand radical civil rights activists and party supporters poured in Philadelphia and, over Labor Day Weekend 1970, converged on Temple University.

Further Developments

Crime was a serious problem too. Primarily drug-related gang warfare plagued the city, and in 1970 crime was rated the city's number one problem in a City Planning Commission survey. The court system was overtaxed and the tactics of the police department under Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo were controversial. Frank Rizzo was known to use repressive actions against people. He was elected mayor in 1971. He was outspoken and he was reelected in 1975. He was divisive too with loyal supporters and passionate opponents. Police and fire departments and cultural institutions were well supported under Rizzo, but other city departments like the Free Library, the Department of Welfare and Recreation, the City Planning Commission and the Streets Department experienced large cuts. The revolutionary black organization of MOVE was created in 1972. It was created by John Africa. Its goal was to promote communal black solidarity, end to police brutality, fighting racism, etc. They embraced green politics and defense of animal rights. There was the 1978 shootout where it happened among MOVE members and Philadelphia police officers. Police James J. Ramp was killed by a shot to the back of the neck. MOVE representatives claimed that he was facing the house at the time and deny MOVE responsibility for his death. Seven other police officers, five firefighters, three MOVE members, and three bystanders were also injured. Nine MOVE members were each sentenced to a maximum of 100 years in prison for third degree murder for Ramp's killing. Seven of the nine first became eligible for parole in the spring of 2008, but were denied it. Parole hearings now occur yearly. Many MOVE members died in prison. The 1985 bombing is the event that more people know about. It happened in Southwest Philadelphia.