President Lyndon Baines Johnson (After 110 Years After his Birth)

Lyndon Baines Johnson was one of the most historic, controversial, and complicated Presidents in history. He had a dual legacy as President. He enriched the lives of millions of Americans with his powerful, progressive Great Society social programs (along with laws promoting civil rights and voting rights, which is very great). Yet, he also ended his Presidency with his reckless, wrong policies involving not only the Vietnam War but imperialism in other nations too (as advanced by many generals back then). Therefore, LBJ made incorrect, imperialist foreign policy decisions in other areas in general as he was a Cold Warrior and a radical anti-Communist. LBJ was born in Texas and he was in the military for a time. He politically allied with Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a young man. LBJ believed in the precepts of the New Deal, which transformed America forever. Later, he taught poor Mexican children in Texas as a schoolteacher and became a Congressman. Gaining seniority via his efforts enabled him to gain much political power. He is known for being vulgar, sensitive, and crass. During the 1960 Presidential primary, he ran for President. He was shocked that the younger John F. Kennedy defeated him. Then, JFK decided to want him to be his running mate. He agreed.

During the 1960 Presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon for the Presidency. Lyndon Baines Johnson was originally the Vice President. LBJ followed Kennedy’s lead, but he disagreed with Kennedy’s policies in Vietnam. He wanted JFK to be more aggressive in terms of military action. After Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963, LBJ was President. Many of the laws that Johnson signed or passed came from the previous Kennedy Administration. He won the 1964 election by his own merit against Barry Goldwater. Johnson talked with Dr. King regularly on civil rights and voting rights. LBJ worked with Texas liberal Democrat Ralph Yarborough and other progressive leaders to pass civil rights and voting rights legislation. Johnson knew that the Jim Crow South was ending and he had to bring folks (who disagreed with him) to realize that a change was necessary.

He signed both the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965. He promoted immigration legislation in 1965. He accelerated military action in the Vietnam War which caused his Presidency to disintegrate, because his policies never caused a real resolution (it only extended the destructiveness of the war). Fulbright and other liberal Congress people opposed him on Vietnam. Rebellions existed all across America from Watts to Detroit (and his cabinet said that he originally failed to understand the complex origin of the rebellions which dealt with hurt, neglect, racial oppression, police brutality, and economic injustice). His Great Society programs were stripped of funding to fund the war in Vietnam by the late 1960’s (this reality grew the anti-war movement). As a product of this, inflation grew in America while the economies of Japan and Western Europe increased in power. Robert F. Kennedy (his nemesis. LBJ and RFK didn't get along with each other at all) ran for President on March 1968. In terms of the environment, he was the most progressive President (on the environmental issue) of the 20th century. Under disaster after disaster, the capitalist President LBJ decided not to run for President again during 1968 after the Tet Offensive. He lived to see some of the last, major social reforms of the post-World War II era. LBJ made a combination of great policies and great mistakes. His Presidency ended in 1969. Now, it’s time to reflect on his life and legacy as President of the United States of America.

Early Life

Lyndon Baines Johnson was born on August 27, 1908 near Stonewall, Texas. He was born in a small farmhouse on the Pedernales River. He was the oldest of five children. His parents were Samuel Ealy Johnson Jr. and Rebekah Baines. His only brother was Sam Houston Johnson. His three sisters were Rebekah, Josefa, and Lucia. The nearby small town of Johnson City, Texas was named after LBJ’s cousin, James Polk Johnson. James’ ancestors moved west from Georgia. LBJ had English, German, and Ulster Scots ancestry. His patrilineal descent goes back to John Johnson, who was born in Dumfriesshire, Scotland in 1590. He was maternally descended from pioneer Baptist clergyman George Washington Baines. Baines pastored eight churches in Texas as well in Arkansas and Louisiana. Baines was the grandfather of Johnson’s mother, who was also the president of Baylor University during the U.S. Civil War. Samuel Ealy Johnson Sr. was LBJ’s grandfather. Samuel was raised Baptist and was a Christian Church member (Disciples of Christ) for a time. In his later years, Samuel became a Christadelphian. Johnson’s father also was part of the Christadelphian Church at the end of his life. LBJ’s positive attitude towards Jewish people was inspired by his religious beliefs among his family (especially by his grandfather). Johnson's favorite Bible verse came from the King James Version of Isaiah 1:18. "Come now, and let us reason together ..."

When LBJ was in school, he was talkative and awkward as a youth. He was elected president of his 11th grade class. By 1924, he graduated from Johnson City High School. In that school, he participated in public speaking, debate, and baseball. He graduated at the age of 15, so he was the youngest member of his class. His parents wanted him to attend college, so he did. He enrolled at the Southwest Texas State Teachers College (SWTSTC) in the summer of 1924, where students from unaccredited high schools could take the 12th-grade courses needed for admission to college. He left the school just weeks after his arrival, and decided to move to Southern California. He worked at his cousin's legal practice and in various odd jobs before returning to Texas, where he worked as a day laborer.

By 1926, Johnson enrolled at SWTSTC (now Texas State University). He worked his way around school. He worked in debate and campus politics. He edited the school newspaper called, “The College Star.” During his college years, he refined his skills of persuasion and political organization. His paused his studies (from 1928-1929) to teach Mexican- American children at the segregated Welhasusen School in Cotulla, Texas. That was 90 miles south of San Antonio in La Salle County. The job allowed him to save money, so he could complete his education. He graduated by 1930. He briefly taught at Pearsall High School before taking a position as a teacher of public speaking at Sam Houston High School in Houston. He reminisced about his time educating Mexican Americans when he spoke in San Marcos in 1965 (in after signing the Higher Education Act of 1965).

He entered into politics early on. Richard M. Kleberg won a 1931 special election to represent Texas in the United States House. Later, he appointed Johnson as his legislative secretary. Recommendations from his father and that of State Senator Welly Hopkins (who LBJ campaigned for in 1930) caused LBJ to get the position. Kleberg had little interest in performing day to day duties as a Congressman. He delegated those duties to Johnson. After Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the 1932 Presidential election, Johnson became as staunch supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal. LBJ shook hands with FDR in 1937. Johnson was elected speaker of the “Little Congress” of Congressional aides where he cultivated Congressmen, newspapermen, and lobbyists. Johnson’s friends soon included aides to President Roosevelt as well as fellow Texans like Vice President John Nance Garner and Congressman Sam Rayburn.

Lyndon Baines Johnson married Claudia Alta Taylor (known as “Lady Bird” of Karnack, Texas) on November 17, 1934. This was after he attended Georgetown University Law Center for many months. The wedding was officiated by Rev. Arthur R. McKinstry at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in San Antonio. They had two daughters, Lynda Bird, born in 1944, and Luci Baines, born in 1947. Johnson gave his children names with the LBJ initials; his dog was Little Beagle Johnson. His was the LBJ Ranch; his initials were on his cufflinks, ashtrays, and clothes. In 1935, he was appointed head of the Texas National Youth Administration, which enabled him to use the government to create education and job opportunities for young people. He resigned two years later to run for Congress. Johnson, a notoriously tough boss throughout his career, often demanded long workdays and work on weekends. He was described by friends, fellow politicians, and historians as motivated by an exceptional lust for power and control. As Johnson's biographer Robert Caro observes, "Johnson's ambition was uncommon—in the degree to which it was unencumbered by even the slightest excess weight of ideology, of philosophy, of principles, of beliefs.”

Congress

By 1937, Johnson successfully campaigned in a special election for Texas’s 10th congressional district. This district involved Austin and the surrounding hill country. He ran on a New Deal platform. He was aided by his wife effectively. He served in the House from April 10, 1937 to January 3, 1949. President Franklin D. Roosevelt welcomed him as an ally. He was a conduit for information, especially when it relates to Texas internal politics. He worked with LBJ on the machinations of Vice President John Nance Garner and Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn. Johnson was soon appointed to the Naval Affairs Committee. He worked involving rural electrification and other improvements in his district. LBJ steered the projects towards contractors. He personally knew contractors like the Brown Brothers, Herman and George. They would finance much of LBJ’s future political career. He ran for the Democratic U.S. Senate nomination in a special election in 1941. His main opponent was the sitting Governor of Texas. He was the businessman and radio personality W. Lee O’Daniel. Johnson narrowly lost the Democratic primary, which was tantamount to the election. O’Daniel received 175,590 votes (30.49%), and Johnson 174,279 votes (30.26%). Lyndon Baines Johnson was in active military duty from 1941 to 1942. On June 21, 1940, he was appointed a Lieutenant Commander of the U.S. Naval Reserve. He served as a U.S. Congressman during this time. He was called to active duty three days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 7, 1941. He was ordered to report to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations in D.C. for instruction and training.

After he was trained, LBJ asked Undersecretary of the Navy James Forrestal for a combat assignment. He was sent instead to inspect the shipyard facilities in Texas and on the West Coast. By the spring of 1942, President Roosevelt needed his own reports on what conditions were like in the Southwest Pacific. FDR wanted information from up the military command. He wanted a trusted political aide to send him the information. Forrestal suggested Johnson to do it. So, FDR assigned Johnson to a three man survey team of the Southwest Pacific. Johnson reported to General Douglas MacArthur in Australia. He had 2 U.S. Army officers who went to the 22nd Bomb Group base. This was assigned the high risk mission of bombing the Japanese airbase at Lae in New Guinea. Johnson’s roommate was an army second lieutenant who was a B-17 bomber pilot. On June 9, 1942, he volunteered as an observer for an air strike mission on New Guinea by eleven B-26 bombers that included his roommate in another plane. While on the mission, his roommate and his crew’s B-26 bomber was shot down with none of the eight men surviving the crash into the water. There are different reports on what happened to the B-26 bomber carrying Johnson during the mission.

Robert Caro is Johnson’s biographer. He accepts Johnson’s account. He said that it’s supported by testimony from the aircrew. Also, the aircraft was attacked, disabling one engine, and it turned back before reaching its objective, though remaining under heavy fire. Others claim that it turned back because of generator trouble before reaching the objective and before encountering enemy aircraft and never came under fire. This is said to be supported by official flight records. Other airplanes that continued to the target came under fire near the target at about the same time that Johnson's plane was recorded as having landed back at the original airbase. MacArthur recommended Johnson for the Silver Star for gallantry in action. After it was approved by the army, he personally presented the medal to Johnson, with a citation. Johnson used a camera as an observer. He reported to Roosevelt and to the Navy leaders. He said that the conditions were deplorable and unacceptable. He argued that the South West Pacific needed a higher priority and a larger share of war supplies immediately. Warplanes were sent.

He wanted Forrestal to know that the Pacific Fleet needed a critical 6,800 additional experienced men. Johnson prepared a 12-point program to upgrade the effort in the region. He wanted “greater cooperation and coordination within the various commands and between the different war theaters." Congress responded by making Johnson chairman of a high-powered subcommittee of the Naval Affairs Committee, with a mission similar to that of the Truman Committee in the Senate. He probed the peacetime "business as usual" inefficiencies that permeated the naval war and demanded that admirals shape up and get the job done. Johnson went too far when he proposed a bill that would crack down on the draft exemptions of shipyard workers if they were absent from work too often; organized labor blocked the bill and denounced him. Johnson's biographer, Robert Dallek concludes, "The mission was a temporary exposure to danger calculated to satisfy Johnson's personal and political wishes, but it also represented a genuine effort on his part, however misplaced, to improve the lot of America's fighting men." In addition to the Silver Star, Johnson received the American Campaign Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal. He was released from active duty on July 17, 1942 and remained in the Navy Reserve, later promoted to commander on October 19, 1949 (effective June 2, 1948). He resigned from the Navy Reserve effective January 18, 1964.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was in the U.S. Senate from 1949 to 1961. During the 1948 elections, Johnson ran for the Senate. He won in a highly controversial result in a three way Democratic Party primary. Johnson faced a well-known former governor, Coke Stevenson and George Peddy, who was a former state representative of District 8 in Shelby County. Johnson drew crowds to fairgrounds with his rented helicopter named “The Johnson City Windmill.” He raised money to flood the state with campaign circulars. He won other conservatives by voting for the Taft-Hartley act (which curbed union power) as well as him criticizing unions. Stevenson came in first, but he lacked a majority. Therefore, a runoff was held. Johnson campaigned harder while Stevenson’s efforts slumped. The runoff took about a week. It was handled by the Democratic State Central Committee, because it was a party primary. Johnson announced that he was the winner by 87 votes out of 988,295 cast. The Committee voted to certify Johnson's nomination by a majority of one (29–28), with the last vote cast on Johnson's behalf by Temple, Texas, publisher Frank W. Mayborn.

There were many allegations of voter fraud; one writer alleges that Johnson's campaign manager, future Texas governor John B. Connally, was connected with 202 ballots in Precinct 13 in Jim Wells County where the names had curiously been listed in alphabetical order with the same pen and handwriting, just at the close of polling. Some of these voters insisted that they had not voted that day. Robert Caro argued in his 1989 book that Johnson had thus stolen the election in Jim Wells County, and that 10,000 ballots were also rigged in Bexar County alone. Election judge Luis Salas said in 1977 that he had certified 202 fraudulent ballots for Johnson. The state Democratic convention upheld Johnson. Stevenson went to court, but Johnson prevailed—with timely help from his friend Abe Fortas. He soundly defeated Republican Jack Porter in the general election in November and went to Washington, permanently dubbed "Landslide Lyndon." Johnson, dismissive of his critics, happily adopted the nickname. Since the beginning of his federal political career, controversy abounds in that part of his life.

Soon, LBJ was a freshman Senator. He made many courtships with older senators like Senator Richard Russell, who was Democrat from Georgia. Russell was part of the conservative coalition and was probably the most powerful man in the Senate during that time. He or LBJ wanted to gain Russell’s favor like he courted Sam Rayburn and gained his crucial support in the House. He was appointed to the Senate Armed Services Committee. Later in 1950, he helped create the Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee. Johnson became its chairman and conducted investigations of defense costs and efficiency. These investigations revealed old investigations and demanded actions that were already being taken in part by the Truman Administration, although it can be said that the committee's investigations reinforced the need for changes. Johnson gained headlines and national attention through his handling of the press, the efficiency with which his committee issued new reports, and the fact that he ensured that every report was endorsed unanimously by the committee. Johnson used his political influence in the Senate to receive broadcast licenses from the Federal Communications Commission in his wife's name. After the 1950 general elections, Johnson was chosen as Senate Majority Whip in 1951 under the new Majority Leader, Ernest McFarland of Arizona, and served from 1951 to 1953.

After the 1952 general election, Republicans won a majority in both the House and the Senate. Many defeated Democrats including McFarland, who lost to the newcomer Barry Goldwater. In January of 1953, Johnson was chosen by Democrats to be the minority leader. He was the most junior Senator ever elected to this position. One of his first actions was to eliminate the seniority system in making appointments to committees while retaining it for chairmanships. LBJ was re-elected to the Senate after the 1954 election. By this time, Democrats won the majority of the Senate. Johnson was now the majority leader. Former majority leader William Knowland became minority leader. Johnson's duties were to schedule legislation and help pass measures favored by the Democrats. Johnson, Rayburn and President Dwight D. Eisenhower worked well together in passing Eisenhower's domestic and foreign agenda. During the Suez Crisis, Johnson tried to prevent the U.S. government from criticizing the Israeli invasion of the Sinai Peninsula. Johnson was upset at the Soviets flying its first artificial Earth satellite Sputnik 1 in space. Back then, many had a paranoia that the Soviets wanted to take over the whole world and implement a brutal, totalitarian empire. Of course, that assumption is false. This reality caused the passage of the 1958 National Aeronautics and Space Act, which established the civilian space agency of NASA.

Historians Caro and Dallek consider Lyndon Johnson the most effective Senate majority leader in history. He was unusually proficient at gathering information. One biographer suggests he was "the greatest intelligence gatherer Washington has ever known", discovering exactly where every Senator stood on issues, his philosophy and prejudices, his strengths and weaknesses and what it took to get his vote. Robert Baker claimed that Johnson would occasionally send senators on NATO trips in order to avoid their dissenting votes. Central to Johnson's control was "The Treatment." The Treatment was about LBJ using persuasion by intimidation, talks, and movements of his body in order for him to convince congressional people to vote his way. A 60-cigarette-per-day smoker, Johnson suffered a near-fatal heart attack on July 2, 1955. He abruptly gave up smoking as a result, with only a couple of exceptions, and did not resume the habit until he left the White House on January 20, 1969. The 1960 Presidential election in America changed the world forever.

The 1960 Presidential Election

LBJ’s success in the Senate made him a potential Democratic presidential candidate. He was praised by the Texas delegation at the Party’s national convention in 1956 and appeared to be in a position to run for the 1960 nomination. Jim Rowe urged Johnson to run a campaign in early 1959. Yet, Johnson thought it better to wait. He thought that John Kennedy’s efforts would create a division in the ranks which could then be exploited. Rowe finally joined the Humphrey campaign in frustration, another move which Johnson thought played into his own strategy. Johnson made a late entry in the campaign by July of 1960. This was about his reluctance to leave Washington. Back during that time, his rival Kennedy campaign had fought to secure a substantial early advantage among Democratic state party officials. Johnson underestimated Kennedy’s endearing qualities of charm and intelligence, as compared to his own reputation as the more crude and wheeling dealing “Landslide Lyndon.” Caro suggested that Johnson’s hesitancy to run was about his fear of failure. Johnson criticized Kennedy because of his youth, poor health, and failure to take a position involving Joseph McCarthy. He formed a “Stop Kennedy” collation with Adlai Stevenson, Stuart Symington, and Hubert Humphrey, but it proved a failure.

Johnson received 409 votes on the only ballot at the Democratic convention to Kennedy's 806, and so the convention nominated Kennedy. Tip O'Neill was a representative from Kennedy's home state of Massachusetts at that time, and he recalled that Johnson approached him at the convention and said, "Tip, I know you have to support Kennedy at the start, but I'd like to have you with me on the second ballot." O'Neill replied, "Senator, there's not going to be any second ballot."

Labor leaders were unanimous in their opposition to Johnson. According to Kennedy’s Special Counsel Myer Feldman and to Kennedy himself, it is impossible to reconstruct the precise manner in which Johnson’s vice-presidential nomination ultimately took place. Kennedy did realize that he could not be elected without support of traditional Southern Democrats, most of whom had backed Johnson. Nevertheless, labor leaders were unanimous in their opposition to Johnson. After much back and forth with party leaders and others on the matter, Kennedy did offer Johnson the vice-presidential nomination at the Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel at 10:15 am on July 14. The morning after he was nominated and Johnson accepted. From that point to the actual nomination that evening, the facts are in dispute in many respects. Convention chairman Le Roy Collins’ declaration of a two-thirds majority in favor by voice is even disputed. Seymour Hersh said that Robert F. Kennedy hated Johnson for his personal attacks on the Kennedy family. Hersh said that his brother offered the position to Johnson out of just courtesy, expecting him to decline. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. concurred with Robert Kennedy's version of events, and put forth that John Kennedy would have preferred Stuart Symington as his running-mate, alleging that Johnson teamed with House Speaker Sam Rayburn and pressured Kennedy to favor Johnson.

The biographer Robert Caro offered a different perspective. He wrote that the Kennedy campaign was desperate to win what was forecast to be a very close election against Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. Johnson was needed on the ticket to help carry Texas and the Southern states. Caro’s research showed that on July 14, John Kennedy started the process while Johnson was still asleep. At 6:30 am, John Kennedy asked Robert Kennedy to prepare an estimate of upcoming electoral votes including Texas. Robert called Pierre Salinger and Kenneth O’Donnell to assist him. Salinger realized the ramifications of counting Texas votes as their own. He asked him whether he was considering a Kennedy-Johnson ticket. Robert replied, “Yes.” Caro contends that it was then that John Kennedy called Johnson called Johnson to arrange a meeting. He also called Pennsylvania governor David L. Lawrence (a Johnson backer) to require that he nominate Johnson for vice President if Johnson were to accept the role. According to Caro, Kennedy and Johnson met and Johnson said that Kennedy would have trouble with Kennedy supporters who were anti–Johnson. Kennedy returned to his suite to announce the Kennedy-Johnson ticket to his closest supporters, including northern political bosses. O'Donnell was angry at what he considered a betrayal by Kennedy, who had previously cast Johnson as anti-labor and anti-liberal.

Afterwards, Robert Kennedy visited labor leaders who were extremely unhappy with the choice of Johnson and, after seeing the depth of labor opposition to Johnson, Robert ran messages between the hotel suites of his brother and Johnson—apparently trying to undermine the proposed ticket without John Kennedy's authorization. Caro continues in his analysis that Robert Kennedy tried to get Johnson to agree to be the Democratic Party chairman rather than vice president. Johnson refused to accept a change in plans unless it came directly from John Kennedy. Despite his brother's interference, John Kennedy was firm that Johnson was who he wanted as running mate; he met with staffers such as Larry O'Brien, his national campaign manager, to say that Johnson was to be vice president. O'Brien recalled later that John Kennedy's words were wholly unexpected, but that after a brief consideration of the electoral vote situation, he thought "it was a stroke of genius.” When John and Robert Kennedy next saw their father Joe Kennedy, he told them that signing Johnson as running mate was the smartest thing that they had ever done.

During the time of LBJ’s vice presidential run, Johnson also sought a third term in the U.S. Senate. According to Robert Caro, "On November 8, 1960, Lyndon Johnson won election for both the vice presidency of the United States, on the Kennedy-Johnson ticket, and for a third term as senator (he had Texas law changed to allow him to run for both offices)." When he won the vice presidency, he made arrangements to resign from the Senate, as he was required to do under federal law, as soon as it convened on January 3, 1961. (In 1988, Lloyd Bentsen, the vice presidential running mate of Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, and a Senator from Texas, took advantage of "Lyndon's law," and was able to retain his seat in the Senate despite Dukakis' loss to George H. W. Bush). Johnson was re-elected Senator with 1,306,605 votes (58 percent) to Republican John Tower's 927,653 (41.1 percent). Fellow Democrat William A. Blakley was appointed to replace Johnson as Senator, but Blakley lost a special election in May 1961 to Tower. Now, Lyndon Baines Johnson became the Vice President of America back in 1961.

When Clare Boothe Luce later asked him why he would accept the nomination to be a Vice Presidential candidate, he answered: “Clare, I looked it up: one out of every four Presidents has died in office. I’m a gamblin’ man, darlin’, and this is the only chance I got.”

Vice President

After the 1960 election, LBJ was concerned about the traditionally ineffective nature of his new office. He wasn't used this office at first. He at first wanted a transfer of the authority of the Senate majority leader to the vice Presidency since that office made him President of Senate. Yet, he faced great opposition from the Democratic Caucus including members whom he had counted as his supporters. Therefore, Johnson wanted to increase his influence within the executive branch. He drafted an executive order for Kennedy's signature giving Johnson "general supervision" over matters of national security. He wanted all government agencies to cooperate fully with the vice President in the carrying out of these assignments. JFK responded was to sign a non-binding letter requesting Johnson to "review" national security policies instead. John F. Kennedy similar turned down early requests from Johnson to be given an office adjacent to the Oval Office, and to employ a full time Vice Presidential staff within the White House. He finally gained more influence in the White House by 1961. Kennedy appointed Johnson's friend Sarah T. Hughes to a federal judgeship and Johnson had tried and failed to garner the nomination for Hughes at the beginning of his vice presidency. House Speaker Sam Rayburn wrangled the appointment from Kennedy in exchange for support of an administration bill.

It is no secret that many members of the Kennedy White House were contemptuous of Johnson including the President's brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. They ridiculed his comparatively brusque, crude manner. Congressman Tip O'Neill recalled that the Kennedy men "had a disdain for Johnson that they didn't even try to hide....They actually took pride in snubbing him." John F. Kennedy, however, made efforts to keep LBJ busy, informed, and the White House often telling aides, "I can't afford to have my vice president, who knows every reporter in Washington, going around saying we're all screwed up, so we're going to keep him happy." JFK appointed him to jobs such as head of the President's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunities, through which he worked with African Americans and other minorities. Kennedy may have intended this to remain a more nominal position, but Taylor in his "Pillar of Fire" contends that Johnson pushed the Kennedy administration's actions further and faster for civil rights than Kennedy originally intended to go.

Branch wrote about the irony of Johnson being the advocate for civil rights, when the Kennedy family had hoped that he would appeal to conservative southern voters. In particular, he noted the Johnson's Memorial Day May 30, 1963 speech at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania as being a catalyst that led to more action. He or LBJ said the following words at Gettysburg:

"...One hundred years later, the Negro remains in bondage to the color of his skin.

The Negro today asks justice.

We do not answer him--we do not answer those who lie beneath this soil--when we

reply to the Negro by asking, "Patience."

It is empty to plead that the solution to the dilemmas of the present rests on

the hands of the clock. The solution is in our hands. Unless we are willing to

yield up our destiny of greatness among the civilizations of history, Americans

--white and Negro together--must be about the business of resolving the challenge

which confronts us now...Until justice is blind to color, until education is unaware of race, until opportunity is unconcerned with the color of men's skins, emancipation will be a proclamation but not a fact.

To the extent that the proclamation of emancipation is not fulfilled in fact, to that extent we shall have fallen short of assuring freedom to the free..."

LBJ took on many diplomatic missions. President John F. Kennedy gave him limited insights into global issues. He gave him more opportunities at promoting his interests. He attended Cabinet and National Security Council meetings. Kennedy gave Johnson control over all Presidential appointments involving Texas. He appointed him the chairman of the President's Ad Hoc Committee for Science. JFK also appointed Johnson as the Chairman of the National Aeronautics Space Council. The Soviet beat the U.S. with the first manned spaceflight on April of 1961. Kennedy gave Johnson the task of evaluating the state of the U.S. space program and recommending a project that would allow the U.S. to catch up or beat the Soviets.

Johnson responded with a recommendation that the US gain the leadership role by committing the resources to embark on a project to land an American on the Moon in the 1960's. Kennedy assigned priority to the space program, but Johnson's appointment provided potential cover in case of a failure.

Lyndon Johnson was touched by a Senate scandal in August of 1963. It was when Bobby Baker or the Secretary of the Majority Leader of Senate (and a protege of Johnson's) came under investigation by the Senate Rules Committee. Baker was accused of the allegations of bribery and financial malfeasance. One witness said that Baker had arranged for the witness to give kickbacks for the Vice President. Baker resigned in October, and the investigation did not expand to Johnson. The negative publicity from the affair fed rumors in Washington circles that Kennedy was planning on dropping Johnson from the Democratic ticket in the upcoming 1964 presidential election. However, on October 31, 1963, a reporter asked if he intended and expected to have Johnson on the ticket the following year. Kennedy replied, "Yes to both those questions." There is little doubt that Robert Kennedy and Johnson hated each other, yet John and Robert Kennedy agreed that dropping Johnson from the ticket could produce heavy losses in the South in the 1964 election, and they agreed that Johnson would stay on the ticket.

Early Presidency

President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963. Lyndon Baines Johnson was quickly sworn in as President on Air Force One in Dallas, Texas. This was about 2 hours and 8 minutes after John F. Kennedy was assassinated. Immediately, many people believed that it was a conspiracy. He was sworn in by the U.S. District Judge Sarah T. Hughes, family friend. In the rush, a Bible wasn't found. So, Johnson took the oath of office suing a Roman Catholic missal from President Kennedy's desk. There is the famous photograph from Cecil Stoughton which showed Johnson taking the oath of office as Mrs. Kennedy looks on.This took place abroad a presidential aircraft. Johnson during his early time as President saw a healthy economy, steady growth, and low unemployment. There was foreign policy issues. The civil rights movement grew into new hegiths while racism was widespread in America. During his Presidency, he focused both on domestic policy and the Vietnam War, especially after 1966.

At first, LBJ moved into Washington and wanted an immediate transition to provide stability. The nation grieved the death of JFK. Immediately, he called for the passage of civil rights legislation. In the days following the assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson made an address to Congress saying that "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long." American grief over the death of President John F. Kennedy influenced the passage of civil rights legislation. Much of Kennedy's plans from anti-poverty measures to civil rights bills were passed under the Johnson administration. On November 29, 1963 just one week after Kennedy's assassination, Johnson issued an executive order to rename NASA's Apollo Launch Operations Center and the NASA/Air Force Cape Canaveral launch facilities as the John F. Kennedy Space Center. Cape Canaveral was officially known as Cape Kennedy from 1963-1973. In essence, LBJ would be much more progressive than Kennedy on domestic issues (as President), but he would unfortunately be much more reactionary than John F. Kennedy on foreign policy issues, especially as it related to the Vietnam War plus Cold War issues.

LBJ supported the Warren Commission as a means for him to head off many people who viewed the Kennedy assassination as a conspiracy. He organized a panel headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and other people. The commission has been disputed and debated for years and decades. The Warren Commission said that Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone in the assassinated. People, who supported the view of conspiracy, opposed the results since day one. LBJ retained many senior Kennedy appointees. He even retained Robert Kennedy as Attorney General. RFK and LBJ didn't get along. Robert Kennedy would leave to run for the Senate in 1964. Johnson had no official chief of staff. Walker Jenkins was the first among a handful of equals and presided over the details of daily operations at the White House. George Reedy was the Johnson second longest serving aide. He assumed the post of press secretary when John F. Kennedy's own Pierre Salinger left that post in March 1964.

Horace Busby was another "triple-threat man," as Johnson referred to his aides. He served primarily as a speech writer and political analyst. Bill Moyers was the youngest member of Johnson's staff. He handled scheduling and speechwriting part-time.

He wanted to sign legislation immediately. He worked with Harry F. Byrd of Virginia to negotiate a reduction in the budget below $100 billion in exchange to pass the Revenue Act of 1964 (which was a tax cut). Congressional approval followed at the end of February and this caused him to go onward with civil rights.

The Civil Rights Movement

President John F. Kennedy submitted to Congress a civil rights bill on June of 1963. He faced strong opposition. President Johnson took on this cause. He asked Robert Kennedy to spearhead the undertaking for the administration on Capitol Hill. The historian Robert Caro wrote that the bill Kennedy had submitted was facing the same activists who prevented the passage of civil rights bill in the past. Southern congressmen and senators used congressional procedure to prevent it from coming to a vote. They even held up all of the major bills Kennedy had proposed and were considered urgent. They held up the tax reform bill in order to force the bill's supporters to pull it. LBJ knew of the procedural tactics. Harry Truman submitted a civil rights bill 15 years earlier and it was held up. In that fight, a rent-control renewal bill was held up until the civil-rights bill was withdrawn. Believing that the current course meant that the Civil Rights Act would suffer the same fate, he adopted a different strategy from that of Kennedy, who had mostly removed himself from the legislative process. By tackling the tax cut first, the previous tactic was eliminated.

In order for the civil rights bill to be passed in the House, it must get through the Rules Committee. It had held it up in an attempt to end it. So, Johnson decided on a campaign to use discharge petition to force it onto the house floor. Facing a growing threat that they would be bypassed, the House rules Committee approved the bill. It was moved to the floor of the full House and the House passed it shortly thereafter by a vote of 290-110. In the Senate, since the tax bill was passed three days earlier, the anti-civil rights senators used a filibuster as their only remaining tool. Overcoming the filibuster needed the support of over 20 Republicans, who were growing less supportive due to the fact that their party was about to nominate for President a candidate (i.e. Barry Goldwater) who opposed the bill. According to Caro, it was Johnson's ability to convince Republican leader Everett Dirksen to support the bill that amassed the necessary Republican votes to overcome the filibuster in March of 1964. This came after 75 hours of debate. The bill was passed in the Senate by a vote of 71-29. Johnson signed the fortified Civil Rights Act of 1964 on July 2, 1964. Legend has it that the evening after signing the bill, Johnson told an aide, "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican party for a long time to come", anticipating a coming backlash from Southern whites against Johnson's Democratic Party. Biographer Randall B. Woods has argued that Johnson effectively used appeals to Judeo-Christian ethics to garner support for the civil rights law.

LBJ was inspired by FDR as his mentor. He wanted to promote the social justice and many liberal values since it was part of his upbringing and personal philosophy. It is important to support social justice and freedom.

The Great Society and the War on Poverty

Lyndon Baines Johnson wanted a catchy, important slogan for the 1964 campaign to describe his proposed domestic agenda for 1965. Eric Goldman joined the White House in December of 1964. He thought that Johnson's domestic program was best captured in the title of Walter Lippman's book, "The Good Society." Richard Goodwin tweaked it to the "Great Society." This was incorporated in detail as part of a speech for Johnson in May 1964 at the University of Michigan. It dealt with the movements of urban renewal, modern transpiration, clean environment, anti-poverty, healthcare reform, crime control, and educational reform.

By late 1963, Lyndon Baines Johnson launched the initially offensive of his War on Poverty. He recruited Kennedy relative Sargent Shriver, then head of the Peace Corps, to spearhead the effort. On March of 1964, LBJ sent to the Congress the Economic Opportunity Act, which created the Job Corps and the Community Action Program. This was designed to attack poverty locally. This act also created VISTA or the Volunteers in Service to America, a domestic counterpart to the Peace Corps.

In 1964, at Johnson's request, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1964 and the Economic Opportunity Act. This was part of his war on poverty. More legislation came like Head Start, food stamps, and Work Study. During Johnson's years in office, the national poverty rate declined significantly. Americans living below the poverty line dropped from 23 percent to 12 percent. He tried to promote his War on Poverty with an urban renewal effort. He presented it to Congress on January of 1966. It was called the "Demonstration Cities Program." To be eligible a city would need to demonstrate its readiness to "arrest blight and decay and make substantial impact on the development of its entire city." Johnson requested an investment of $400 million per year totaling $2.4 billion. In the fall of 1966 the Congress passed a substantially reduced program costing $900 million, which Johnson later called the Model Cities Program. Changing the name had little effect on the success of the bill; the New York Times wrote 22 years later that the program was for the most part a failure, but government investment in helping cities is legitimate.

The Vietnam War in its Early Years

When Kennedy was assassinated, there were 16,000 American military personnel stationed in Vietnamese lands. They were used to support the South Vietnam in the Vietnam War against North Vietnam. There was the 1954 Geneva Conference that partitioned Vietnam into 2 nations. North Vietnam embraced a Communist government. Johnson believed in the notorious myth of the Domino theory, which meant that if Vietnam became totally Communist, then Southeast Asia plus the rest of the world could be Communist. So, LBJ wanted to send American troops to stop in his mind "Communist expansion." When Johnson took office, he immediately reversed Kennedy's order to withdraw 1,000 military personnel by the end of 1963 (and ultimately all American troops by the end of 1965). In late summer of 1964, LBJ seriously once questioned the value of staying in Vietnam. Yet, he met with Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Maxwell D. Taylor. So, he wanted to stabilize Saigon by promoting military intervention in Vietnam. He expanded the numbers and roles of the American military after the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident happened in August of 1964. It was about allegations from the military that 2 U.S. destroyers were attacked by some North Vietnamese torpedo boats in international waters or 40 miles form the Vietnamese coast in the Gulf of Tonkin. There were contradictory naval communications and reports of the attack. McNamara later admitted that the August 2, 1964 attack between the USS Maddox and North Vietnamese forces did exist while the August 4th event never occured.

LBJ didn't want talk about the Vietnam War during the 1964 election campaign, but he felt forced to respond to the events of Vietnam. So, he sought and obtained from Congress the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7, 1964. He was determined to gain an image on dealing with foreign policy issues. He wanted to prevent criticism that Truman had received involving Korea (since Truman proceeded without congressional endorsement of military action). Johnson wanted his actions to blunt attacks from the Goldwater camp. The 1964 resolution gave congressional approval for use of military force by the commander in chief to repel future attacks and to assist members of SEATO requiring assistance. Johnson, during the campaign, said of wanting South Vietnamese people to have independence without any U.S. offensive posture. That was false. The public's reaction to the resolution at the time was positive—48 percent favored stronger measures in Vietnam and only 14 percent wanted to negotiate a settlement and leave. During the 1964 Presidential campaign, Johnson said constantly that he wanted measured support for Vietnam while avoiding another Koea. In private, he feared that whatever he did wouldn't be totally succesfuly. He wanted to promote the Great Society agenda. His political opponents wanted to divert attention and resources away from the War on Poverty.

The situation on the ground was aggravated in the fall by additional Viet Minh attacks on US ships in the Tonkin Gulf, as well as an attack on Bien Hoa Air Base in South Vietnam. Johnson decided against retaliatory action at the time after consultation with the Joint Chiefs and also after public pollster Lou Harris confirmed that his decision would not detrimentally affect him at the polls. By the end of 1964, there were approximately 23,000 military personnel in South Vietnam. U.S. casualties for 1964 totaled 1,278.

During the winter of 1964-1965, LBJ was pressured by the military to begin a bombing campaign to forcefully resist a communist takeover in South Vietnam. A plurality in the polls at that time was in support of military action against the Communists. Only 26-30 percent of people opposed. Johnson revised his priorities and a new preference for stronger action existed by the end of January 1965. There was another change in the Saigon government by then. He then agreed with Mac Bundy and McNamara, that the continued passive role would only lead to defeat and withdrawal in humiliation. Johnson said, "Stable government or no stable government in Saigon we will do what we ought to do. I'm prepared to do that; we will move strongly. General Nguyễn Khánh (head of the new government) is our boy." The Vietnam War continued.

By 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson decided to advance a systematic bombing campaign on February. This came after a ground report from Bundy recommending immediate U.S. action to avoid defeat. Also, the Viet Cong had just killed eight U.S. advisors and wounded dozens of others in an attack at Pleiku Air Base. The eight week bombing campaign from America was known as Operation Rolling Thunder (which started on March 2, 1965). Johnson wanted no comment that the war effort had to be expanded back then. Many of the advisors believed that short term, benefits will come to America. Long term views were more realistic of an intensification of the conflict. He or LBJ limited information to the public. Johnson was flexible. By March of 1965, Bundy urged the use of ground forces. He believed that American air operations alone couldn't stop Hanoi's actions. So, Johnson approved of an increase in logistical troops of 18,000 to 20,000 troops. There was the the deployment of two additional Marine battalions and a Marine air squadron, in addition to planning for the deployment of two more divisions—and most importantly a change in mission from defensive to offensive operations; nevertheless, he disobligingly continued to insist that this was not to be publicly represented as a change in existing policy.

By mid-June 1965, there were about 82,000 U.S. ground fores in Vietnam. This was an increase of 150 percent. That same month, Ambassador Taylor reported that the bombing offensive against North Vietnam had been ineffective, and that the South Vietnamese army was outclassed and in danger of collapse. Gen. Westmoreland shortly thereafter recommended the president further increase ground troops from 82,000 to 175,000. After consulting with his principals, Johnson, desirous of a low profile, chose to announce at a press conference an increase to 125,000 troops, with additional forces to be sent later upon request. Johnson described himself at the time as boxed in by unpalatable choices—between sending Americans to die in Vietnam and giving in to the communists. If he sent additional troops he would be attacked as an interventionist and if he did not he thought he risked being impeached according to Johnson's thinking. He continued to insist that his decision "did not imply any change in policy whatsoever."Of his desire to veil the decision, Johnson jested privately, "If you have a mother-in-law with only one eye, and she has it in the center of her forehead, you don't keep her in the living room." By October 1965, there were over 200,000 troops deployed in Vietnam. This exercise of imperial militarism by the Johnson administration had no justification.

The 1964 Presidential Election

The 1964 Presidential election was one of the most important elections in human history. It changed the U.S. political landscape forever. The good news is that the far right Republican Barry Goldwater was defeated and many progressive policies were implemented in 1964 and beyond. The bad news is that it ironically enough there came such a huge backlash against progressive policies, that it created unfortunately the Reagan Revolution during the 1980's including ultimately Trumpism during the 21st century. To start, it is important to know the events chronologically. First, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963 caused much heartache in America. Lyndon Baines Johnson had huge popularity and won a landslide. He made history in many ways. The issues around this issue revolved around civil rights, foreign policy, the role of government, taxes, the future, and ultimately the human rights of all Americans. It was a election that dealt with how should the government intervene in promoting the human rights of all people. By late 1963, many people temporarily didn't campaign out of respect for the late President John F. Kennedy. By January 1964, both the Democratic and Republican campaigns existed in high gear to promote their views. The Democratic primary was very short lived. The only Democratic primary challenge of Johnson was by George Wallace of Alabama. He was a racist during the 1960's and promoted states' rights. He went to the North to spread his message of hate and bigotry too. LBJ received over 1 million votes in the Democratic primary while Wallace received almost 700,000 votes in the same primary. The Democratic Convention took place in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The greatest controversy involved the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party or the MFDP. They were formed, because the mainline Democratic delegation of Mississippi were racist and was elected by a white primary system. The MFDP wanted to promote progressive representation.

The segregationists hated the MFDP and the "liberal" Democratic party leaders wanted the MFDP to compromise. The compromise proposal was to have even division of the seats between two Mississippi delegations. Johnson knew that Mississippi would vote for Goldwater anyway, but he didn't want political criticism from the national and world press. He sent Hubert Humphrey to find a compromise. Even black civil rights leaders like Roy Wilkins, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Bayard Rustin wanted a compromise, but some MFDP members heroically refused. Ultimately, the compromise worked and it caused many SNCC members to reject the bourgeois politics of the two party system (The author Carroll Quigley, who was a professor of Georgetown University, wrote that the CFR or the Council on Foreign Relations influenced the Republican and Democratic parties. This is found in his 1966 book entitled, "Tragedy and Hope"). The compromise involved MFDP getting 2 seats. The regular, racist Mississippi delegation was required to pledge to support the party ticket. Also, no future Democratic convention would accept a delegation chosen by a discriminatory poll. Joseph L. Rauh Jr. or the MFDP's lawyer agreed to the deal after refusing to accept it at first. Many white racist delegates from Mississippi and Alabama refused to sign any pledge and left the convention. Many young civil rights workers were offended by the compromise and became more politically independent. Johnson would lose Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, and South Carolina (all former Confederate states).

Lyndon Baines Johnson supported the liberal Hubert Humphrey as his vice Presidential running mate instead of Robert F. Kennedy. RFK and LBJ didn't like each other, because according to Lyndon Johnson, he collaborated with FDR to fire Joseph P. Kennedy because of his controversial views. During the 1950's, Johnson would mock Joe Kennedy and he criticized Joseph McCarthy (or the anti-Communist extremist who promoted violation of democratic rights. RFK and McCarthy were allies during the 1950's because of their anti-Communist views). Also, RFK and LBJ had different personality differences. In early 1964, Robert Kennedy failed to get Johnson to accept him as his running mate. Johnson said that he didn't want any cabinet members to be second place on the Democratic ticket. Johnson made RFK give his speech at the last day of the Convention, so that would be after he selected his running mate Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota.

The Republican primary of 1964 was much more complicated, heated, and contentious. It signified the beginning of the modern day conservative movement in American society. By 1964, the Republican Party of the GOP was divided into conservative and moderate-liberal factions. Back then, conservatives and liberals were heavily represented in both major parties. Today in 2018, most liberals are Democrats and most conservatives are Republicans (there are exceptions of course like third party movements, etc.).

The Republican candidates during the 1964 Republican primary were Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York, Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. from Massachusetts, Governor William Scranton of Pennsylvania, Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine, Representative Walter Judd from Minnesota, Senator Hiram Fong from Hawaii, former Governor Harold Stassen of Minnesota, and Representative John W. Byrnes of Wisconsin.

By 1964, Richard Nixon didn't ran for the election. So, it was open season. Nixon couldn't unite both factions of the moderates and the conservatives in 1960 or in 1964. The conservatives' champion was the Senator from Arizona named Barry Goldwater. Back in the day, many conservatives were based in the Midwest. By the 1950's, they grew more in the South and the West. Conservatives historically wanted a low tax, small federal government. They believed in individual rights and business interests. They also opposed social welfare programs. These conservatives in 1964 hated the moderates, who dominated much of the GOP. The moderate wing was found heavily in the Northeastern region of America.

Since 1940, the Eastern moderates had successfully defeated conservative presidential candidates at the GOP’s national conventions. The conservatives believed the Eastern moderates were little different from liberal Democrats in their philosophy and approach to government. Goldwater’s chief opponent for the Republican nomination was Nelson Rockefeller, the Governor of New York and the longtime leader of the GOP’s liberal-moderate faction.

At first, Nelson Rockefeller was a front runner. He was ahead of Goldwater. Then, in 1963, something happened. That year was 2 years after Rockefeller's divorce from his first wife. He married Margarita Murphy, who was 18 years younger than him. She surrendered her four children to his custody. This would be a scandal back in the 1980's, but imagine the 1960's. This caused a huge uproar among conservatives. There are rumors that Rockefeller had an extramarital affair with her before his divorce. Social conservatives and women voters in the GOP were angry at Rockefeller. After his remarrriage, he lost the lead among Republicans by 20 points overnight. His critics also included Prescott Bush of Connecticut. He was the father of President George H. W. Bush and the grandfather of George W. Bush. Prescott Bush said of Rockefeller that: "...Have we come to the point in our life as a nation where the governor of a great state—one who perhaps aspires to the nomination for president of the United States—can desert a good wife, mother of his grown children, divorce her, then persuade a young mother of four youngsters to abandon her husband and their four children and marry the governor?"

The first primary made Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. the victory in New Hampshire. This shocked many as some expected Goldwater or Rockefeller to win. Cabot later decided that he didn't want the Republican nomination. Goldwater continued to win in Illinois, Texas, and Indiana primaries with little opposition. He won Nebraska after the opposition from the draft-Nixon movement.

Goldwater also won a number of state caucuses and gathered even more delegates. Meanwhile, Nelson Rockefeller won the West Virginia and Oregon primaries against Goldwater, and William Scranton won in his home state of Pennsylvania. Both Rockefeller and Scranton also won several state caucuses, mostly in the Northeast.

The final showdown between Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller existed in the California primary. Goldwater won California. This came after his new wife's child was born. Goldwater won a narrow 51 to 49% margin. Some liberal and moderate Republicans wanted William Scranton or the Governor of Pennsylvania to run against Goldwater, but he lost too. Goldwater won the Republican nomination.

The 1964 Republican Convention in Daly City, California was one of the most bitter conventions in history. Goldwater won. Rockefeller was booed when he was on the podium. Conservatives screamed at him. Moderates and conservatives expressed disdain for each other. Goldwater picked William E. Miller from New York state as his running mate. Goldwater stated that he chose Miller simply because “he drives [President] Johnson nuts." In the convention, Jackie Robinson was heckled and afterwards, he supported LBJ and Humphrey for President respectively in 1964 and in 1968. In accepting his nomination, Barry Goldwater uttered his most famous phrase (a quote from Cicero suggested by speechwriter Harry Jaffa): “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” For many GOP moderates, Goldwater’s speech was seen as a deliberate insult, and many of these moderates would defect to the Democrats in the fall election.

The General election of 1964 was filled with a clear choices. 2 men who had opposite political views ran against each other on the Democratic and Republican sides. There was no ambiguity. It was very overt in the decision that voters had to make. Goldwater rallied conservatives, but he failed to massively expand his base of support, which was his political weakness. He was stuck in his base. One of Barry Goldwater's most evil mistakes was his opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This law promoted federal civil rights. Goldwater opposed the law since he felt it was unconstitutional by virtue of it being a federal government overreach. He said that he wasn't a racist, but he believed that desegregation was a states' rights issue not a national policy issue. That's a lie for many reasons. One is that desegregation deals with people nationwide, and the Fourteenth Amendment promotes citizenship nationwide. Different civil rights law in different states would mean that some states would be more free than others and that wasn't needed. An uniform federal policy as it relates to civil rights is better than multiple states having different types of civil rights laws. Segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment, it violates the freedom of association, and laws can be legally passed federally by Congress in order to end Jim Crow apartheid.

African Americans overwhelmingly supported Johnson because of Goldwater's blunders. Goldwater hypocritically voted in favor of the 1957 and 1960 Civil Rights acts, but only after proposing "restrictive amendments" to them. Goldwater was famous for speaking "off-the-cuff" at times, and many of his former statements were given wide publicity by the Democrats. In the early 1960's, Goldwater had called the Eisenhower administration “a dime store New Deal”, and the former president Eisenhower never fully forgave him or offered him his full support in the election. Goldwater was wrong to say the following words in December of 1961. In a news conference, he said that, "sometimes I think this country would be better off if we could just saw off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea”, a remark which indicated his dislike of the liberal economic and social policies that were often associated with that part of the nation. That comment came back to haunt him, in the form of a Johnson television commercial, as did remarks about making Social Security voluntary and selling the Tennessee Valley Authority. In his most famous verbal gaffe, Goldwater once joked that the U.S. military should “lob one [a nuclear bomb] into the men’s room of the Kremlin” in the Soviet Union.

African Americans overwhelmingly supported Johnson because of Goldwater's blunders. Goldwater hypocritically voted in favor of the 1957 and 1960 Civil Rights acts, but only after proposing "restrictive amendments" to them. Goldwater was famous for speaking "off-the-cuff" at times, and many of his former statements were given wide publicity by the Democrats. In the early 1960's, Goldwater had called the Eisenhower administration “a dime store New Deal”, and the former president Eisenhower never fully forgave him or offered him his full support in the election. Goldwater was wrong to say the following words in December of 1961. In a news conference, he said that, "sometimes I think this country would be better off if we could just saw off the Eastern Seaboard and let it float out to sea”, a remark which indicated his dislike of the liberal economic and social policies that were often associated with that part of the nation. That comment came back to haunt him, in the form of a Johnson television commercial, as did remarks about making Social Security voluntary and selling the Tennessee Valley Authority. In his most famous verbal gaffe, Goldwater once joked that the U.S. military should “lob one [a nuclear bomb] into the men’s room of the Kremlin” in the Soviet Union.

So, Goldwater was a complete extremist during the 1964 election. Moderate Republicans Governors Nelson Rockefeller of New York and George Romney of Michigan refused to support Goldwater and didn't campaign for him. Nixon and Scranton campaigned for Goldwater out of loyalty to the GOP. Nixon did not entirely agree with Goldwater’s political stances and said that it would “be a tragedy” if Goldwater’s platform were not "challenged and repudiated" by the Republicans. The New York Herald-Tribune, a voice for eastern Republicans (and a target for Goldwater activists during the primaries), supported Johnson in the general election. Some moderates even formed a “Republicans for Johnson” organization, although most prominent GOP politicians avoided being associated with it. Goldwater won a libel suit against psychiatrists saying that he was emotionally unfit for office. Of course, Reagan supported Goldwater. Ronald Reagan gave a speech (called A Time for Choosing) praising Goldwater and Reagan was known to compare Medicare to totalitarianism, which is ludicrous. Today, Medicare has helped millions of American lives.

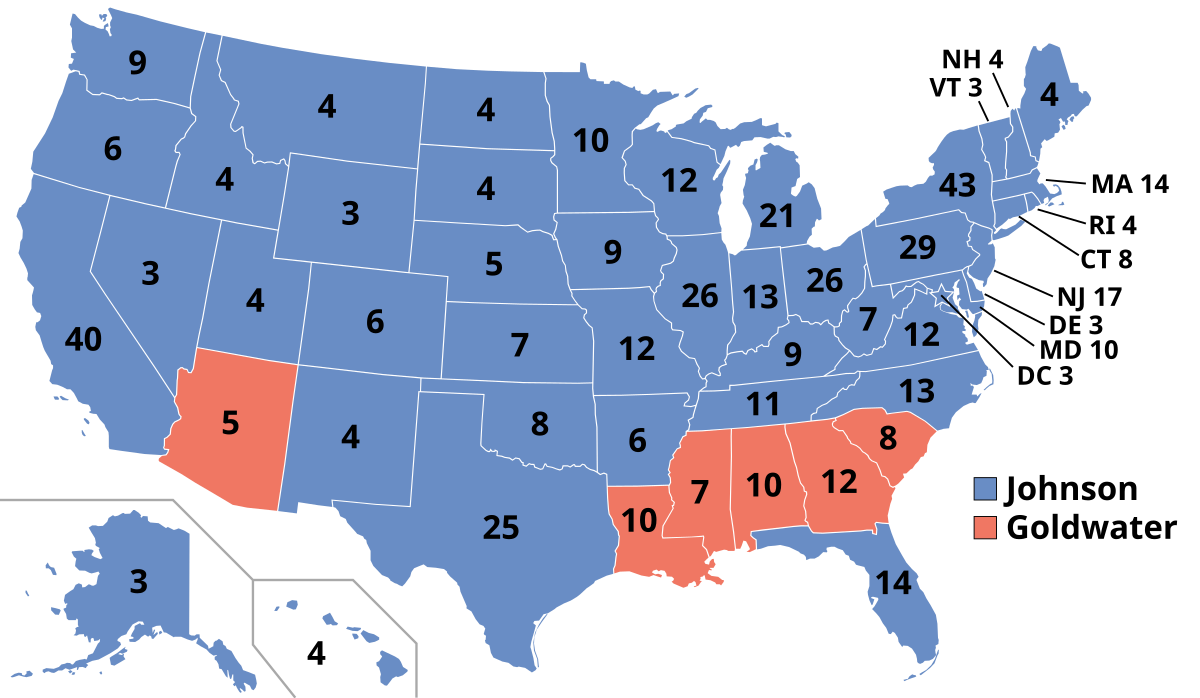

There were many ads and slogans during this election year. The Daisy commercial was very controversial. It showed a girl pulling daisies and the world explodes from a nuclear blast. Johnson implied that Goldwater wanted to provoke nuclear annihilation in the world. Goldwater advocated the use of tactical nuclear weapons in Vietnam. Many voters viewed Goldwater as a right wing extremist. His slogan “In your heart, you know he’s right” was successfully parodied by the Johnson campaign into “In your guts, you know he‘s nuts”, or “In your heart, you know he might” (as in “he might push the nuclear button”), or even “In your heart, he’s too far right." Some cynics wore buttons saying “Even Johnson is better than Goldwater!" LBJ broadcast messages nationwide. Each campaign ended campaign on the week of the death of former President Herbert Hoover on October 20, 1964. Both men attended his funeral. Johnson had a huge lead in the polls before the election. The election on November 3, 1964 caused Lyndon Baines Johnson to have landslide victory. He beat Goldwater in the general election, winning over 61% of the popular vote, the highest percentage since the popular vote first became widespread in 1824. In the end, Goldwater won only his native state of Arizona and five Deep South states—Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, Alabama and South Carolina—which had been increasingly alienated by Democratic civil rights policies. This was the best showing in the South for a GOP candidate since Reconstruction.

The five Southern states that voted for Goldwater swung over dramatically to support him. For instance, in Mississippi, where Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt had won 97% of the popular vote in 1936, Goldwater won 87% of the vote. Of these states, Louisiana had been the only state where a Republican had won even once since Reconstruction. Mississippi, Alabama and South Carolina had not voted Republican in any presidential election since Reconstruction, whilst Georgia had never voted Republican even during Reconstruction (thus making Goldwater the first Republican to ever carry Georgia).

The 1964 election transformed the South. The South afterwards became increasingly Republican. Johnson still had a majority of the popular vote in the eleven former Confederate states. Johnson was the first Democrat to win the state of Vermont in a Presidential election. He carried Maine too. Also, the election caused the defeat of many conservative Republican congressmen. This gave him or Johnson the majority to overcome the conservative coalition to pass great progressive legislation. This was also the first election where the District of Columbia participated in under the 23rd Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Goldwater was defeated and this caused one foundation of the conservative revolution in the future. Johnson passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965 and promoted Great Society programs. After this election, he would lose popularity over his policies towards Vietnam. Many white Southerners became Reagan Democrats and voted for Republicans. This election caused more black people to move away from the Republican Party and vote for Democrats (this trend started since the New Deal with Franklin Delano Roosevelt). Since the 1964 election, Democratic presidential candidates have almost consistently won at least 80–90% of the black vote in each presidential election. The 1964 Presidential election was a very important part of American history indeed.

By Timothy

No comments:

Post a Comment