LBJ Part 2

The Voting Rights Act

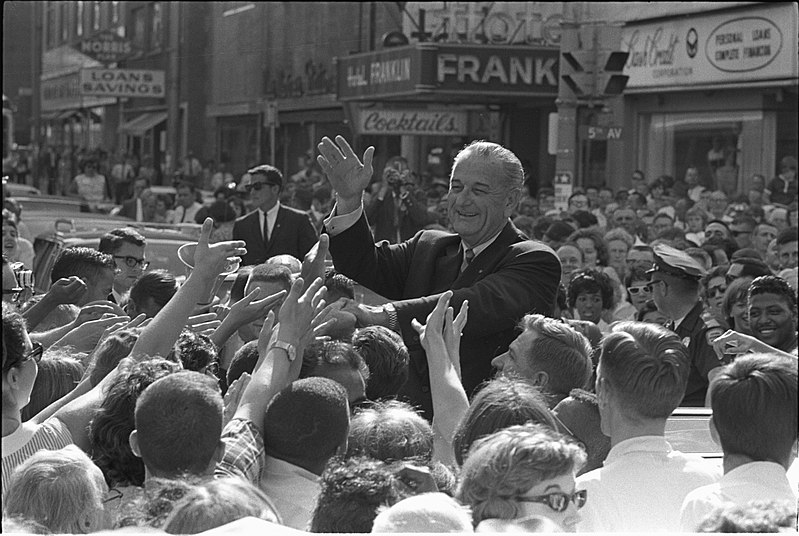

Lyndon Baines Johnson began his elected Presidential term in 1965 with similar motives as he had upon succeeding into office. He wanted to carry forward the plans and programs of the late President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. He was reticent to push southern congressmen even further after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He suspected that their support have been temporarily tapped out. Yet, civil rights activists continued onward in the cause of freedom despite the opposition. The Selma to Montgomery marches were led by Dr. Martin Luther King, the SNCC, the NAACP, and the DCVL. This led Johnson to initiate debate on a voting rights bill in February 1965. Johnson gave a congressional speech—Dallek considers it his greatest—in which he said "rarely at anytime does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself…rarely are we met with the challenge… to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation. The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation."

In 1965, he achieved passage of a second civil rights bill called the Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discrimination in voting thus allowing millions of southern black Americans to vote for the first time. In accordance with the act, several states, "seven of the eleven southern states of the former confederacy" (Alabama, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Virginia) were subjected to the procedure of preclearance in 1965 while Texas, then home to the largest African American population of any state, followed in 1975. The Senate passed the voting rights bill by a vote of 77–19 just after 2 1/2 months and won passage in the House on July, by 333–85. The results were significant. Between the years of 1968 and 1980, the number of southern black elected state and federal officeholders nearly doubled. The act also made a large difference in the numbers of black elected officials nationally. In 1965, a few hundred black office-holders mushroomed to 6,000 in 1989. This law was created by the blood of martyrs like Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo (a civil rights worker from Michigan), and James Reeb. After these murders, Lyndon Baines Johnson went on television to announce the arrest of four Ku Klux Klansmen implicated in her death. He angrily denounced the Klan as a "hooded society of bigots," and warned them to "return to a decent society before it's too late."

Johnson was the first President to arrest and prosecute members of the Klan since President Ulysses S. Grant did so about 93 years earlier. He turned to themes of Christian redemption to push for civil rights, thereby mobilizing support from churches North and South. At the Howard University commencement address on June 4, 1965, he said that both the government and the nation needed to help achieve goals, "To shatter forever not only the barriers of law and public practice, but the walls which bound the condition of many by the color of his skin. To dissolve, as best we can, the antique enmities of the heart which diminish the holder, divide the great democracy, and do wrong—great wrong—to the children of God..." Some view these words as endorsing affirmative action. In 1967, Johnson nominated civil rights attorney Thurgood Marshall to be the first African American justice of the Supreme Court. To head the new Department of Housing and Urban Development, Johnson appointed Robert C. Weaver—the first African-American cabinet secretary in any U.S. Presidential administration.

In 1968 Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which provided for equal housing opportunities regardless of race, creed, or national origin. The impetus for the law's passage came from the 1966 Chicago Open Housing Movement, the April 4, 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the civil unrest across the country following King's death. On April 5, 1968, Johnson wrote a letter to the United States House of Representatives urging passage of the Fair Housing Act. With newly urgent attention from legislative director Joseph Califano and Democratic Speaker of the House John McCormack, the bill (which was previously stalled) passed the House by a wide margin on April 10.

Immigration and Education

President Johnson supported immigration. He signed the Immigration Nationality Act of 1965. It was very sweeping and Senator Edward Kennedy and Senator Robert Kennedy including others looked on while he signed the bill into law. It was a great, necessary law that advanced the awe-inspiring diversity of the American populace. The law ended the overtly racist quotas from the 1920's. The annual rate of inflow doubled between 1965 and 1970, and doubled again by 1990, with dramatic increases from Asia and Mexico. Scholars give Johnson little credit for the law, which was not one of his priorities; he had supported the McCarren-Walters Act of 1952 that was unpopular with reformers.

Johnson in real life used public education in order for him to escape poverty. He believed that education was a cure for ignorance and poverty. He also thought of education as vital component of the American dream, especially for minorities who endured poor facilities and tight fisted budgets from local taxes. That is why he made education a top priority of the Great Society agenda. He wanted to help poor children. After the 1964 landslide brought in many new liberal Congressmen. LBJ launched a legislative effort which took the name of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. The bill sought to double federal spending on education from $4 billion to $8 billion. This was facilitated by the White House. It was passed by the House by a vote of 263 to 153 on March 26. Then, it remarkably passed without change in the Senate by 73 to 8 without going through the usual conference committee. This was a historic accomplishment by President Lyndon Johnson with the billion dollar bill passing as introduced just 87 days before.

Afterward, for the first time, large amounts of money from the federal government came into public school. ESEA was meant to help all public school districts. More money going to districts that had large proportions of students from poor families (which included big cities) was part of the plan. For the first time, private schools (most of them Catholic schools in the inner cities) received services like library funding. This made up of 12 percent of the ESEA budget. Local officials administered the federal funds. By 1977, it was reported that less than half of the funds were actually applied toward the education of children under the poverty line.

Dallek further reports that researchers cited by Hugh Davis Graham soon found that poverty had more to do with family background and neighborhood conditions than the quantity of education a child received. Early studies suggested initial improvements for poor children helped by ESEA reading and math programs, but later assessments indicated that benefits faded quickly and left pupils little better off than those not in the policies. Johnson's second major education program was the Higher Education Act of 1965, which focused on funding for lower income students, including grants, work-study money, and government loans. This policies helped millions of Americans back then and today in many positive ways. Although ESEA solidified Johnson's support among K-12 teachers' unions, neither the Higher Education Act nor the new endowments mollified the college professors and students growing increasingly uneasy with the war in Vietnam. In 1967, Johnson signed the Public Broadcasting Act to create educational television programs to supplement the broadcast networks. PBS came about as a result of this law. I watch PBS and its shows are certainly creative, very educational, and enlightening.

In 1965, Johnson also set up the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts, to support academic subjects such as literature, history, and law, and arts such as music, painting, and sculpture (as the WPA once did).

Healthcare and Other Progressive Policies

Lyndon Johnson's initial effort to improve health care was the creation of the HDCS or the Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Strokes. Combined, these diseases accounted for 71 percent of the nation's deaths in 1962. He wanted to enact recommendations of the commission. So, he asked Congress to funds to set up the Regional Medical Program (RMP) to create a network of hospitals with federally funded research and practice. Congress passed a significantly watered down version. As a back up position, in 1965, Johnson turned his focus to hospital insurance for the aged under Social Security. This program was heavily promoted by Wilbur Mills, Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. It was called Medicare. JFK, before he died, promoted such a universal health care service for the elderly.

President Kennedy gave a speech in Madison Square Garden in New York City to advocate a Medicare system for the senior citizen population. In order to reduce Republican opposition, Mills suggested that Medicare be fashioned in a three tiered system. It includes hospital insurance under Social Security, a voluntary insurance program for doctor visits and an expanded medical welfare program for the poor, known as Medicaid. The bill passed the House by a margin of 110 votes on April 8. The effort in the Senate was considerably more complicated; however, the Medicare bill passed Congress on July 28 after negotiation in a conference committee. Medicare now covers tens of millions of Americans. Johnson gave the first two Medicare cards to former President Harry S. Truman and his wife Bess after signing the Medicare bill at the Truman Library in Independence, Missouri. Medicaid and Medicare have saved lives and helped millions of American lives.

In March of 1965, LBJ sent to Congress a transportation message. He wanted the creation of a new Transportation Department. It included the Commerce Department's Office of Transportation, the Bureau of Public Roads, the Federal Aviation Agency, the Coast Guard, the Maritime Administration, the Civil Aeronautics Board and the Interstate Commerce Commission. The bill passed the Senate after some negotiation over navigation projects; in the House, passage required negotiation over maritime interests and the bill was signed October 15, 1965. On October 22, 1968, Lyndon Johnson signed the Gun Control Act of 1968, one of the largest and farthest-reaching federal gun control laws in American history. Much of the motivation for this large expansion of federal gun regulations came as a response to the assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

During Johnson's administration, NASA used the Gemini manned space program. It developed the Saturn V rocket and its launch facility. It prepared to make its first manned Apollo program flights. On January 27, 1967, that nation was shocked by the following event. This was when the entire crew of Apollo 1 was killed in a cabin fire during a spacecraft test on the launch pad. It stopped Apollo for a while. Johnson didn't promote a Warren style commission. He accepted Administrator James E. Webb's request for NASA to do its own investigation. It hold itself accountable to Congress and the President. LBJ continued to strongly support Apollo through Congressional and press controversy. The program recovered. The first two manned missions, Apollo 7 and the first manned flight to the Moon, Apollo 8, were completed by the end of Johnson's term. He congratulated the Apollo 8 crew, saying, "You've taken ... all of us, all over the world, into a new era." On July 16, 1969, Johnson attended the launch of the first Moon landing mission Apollo 11, becoming the first former or incumbent US president to witness a rocket launch.

1966

A lot of public impatience with the Vietnam War existed in the spring of 1966. LBJ's approval rating during that time reached new lows of 41 percent. Sen. Richard Russell, Chairman of the Armed Services Committee said in June 1966 (which reflected the mood at the time) that to "get it over or get out." Johnson responded by saying to the press, "we are trying to provide the maximum deterrence that we can to communist aggression with a minimum of cost." Johnson believed that the intensified criticism of the war effort was a product of communist subversion and the press relations became strained. That's ludicrous. One of Johnson's major war policy opponent in Congress included the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee whose name was James William Fulbright. Johnson wanted more focused bombing campaign against petroleum, oil, and lubrication facilities in North Vietnam. He desired an accelerated victory. Humphrey, Rusk, and McNamara agreed with this goal. The bombing started in the end of June 1966. During July polling, Americans favored the bombing campaign by a 5 to 1 margin. Yet, in August 1966, a Defense Department study indicated that the bombing campaign had little impact on North Vietnam. By the fall of 1966, multiple sources began to report that progress was made against the North Vietnamese logistics and infrastructure. Johnson was urged to promote peace discussions. Peace initiatives already existed among protesters. English philosopher Bertrand Russell attacked Johnson's policy as "a barbaric aggressive war of conquest" and in June he initiated the International War Crimes Tribunal as a means to condemn the American effort.

The gap with Hanoi was an unbridgeable demand on both sides for a unilateral end to bombing and withdrawal of forces. In August, Johnson appointed Averell Harriman "Ambassador for Peace" to promote negotiations. Westmoreland and McNamara then recommended a concerted program to promote pacification; Johnson formally placed this effort under military control in October. By October 1966, LBJ wanted to promote the war effort still. He organized a meeting with allies in Manila. The meeting included South Vietnamese, Thais, South Koreans, Filipinos, Australians, and New Zealanders. The conference wanted to fight "communist aggression." It claimed to promote democracy and development in Vietnam and across Asia, but obviously the Vietnam War was about promoting capitalist economic interests and overt U.S. imperialism. 63 percent of Americans supported the Vietnam War in November of 1966. Dwight Eisenhower talked with LBJ on many issues too. By the end of 1966, the policies of Johnson didn't work to end the conflict. The air campaign didn't work. Johnson then agreed to McNamara's new recommendation to add 70,000 troops in 1967 to the 400,000 previously committed. While McNamara recommended no increase in the level of bombing, Johnson agreed with CIA recommendations to increase them. The increased bombing began despite initial secret talks being held in Saigon, Hanoi and Warsaw. While the bombings ended the talks, North Vietnamese intentions were not considered genuine by the Americans when the Vietnamese people for centuries were victims of invasion from Chinese and Western forces.

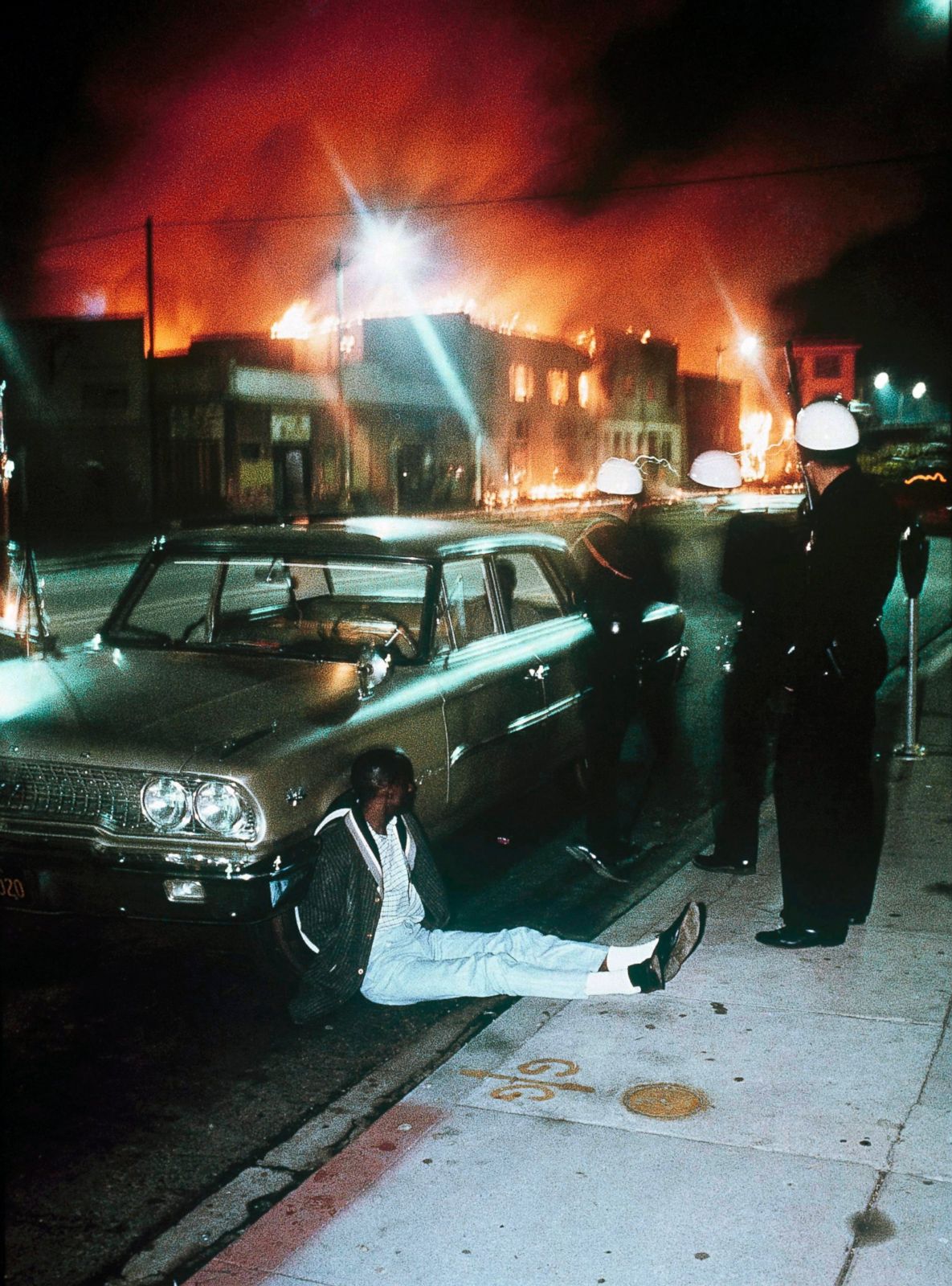

Urban Rebellions

Urban rebellions in America existed in a high level from 1963 (as early as the 1963 rebellion in Cambridge, Maryland and Birmingham, Alabama) to 1971. It was a time of change. Many black and poor people were tired of police brutality, the slow pace of civil rights advancement, and poverty plus economic injustice. As the Kerner Commission accurately stated in 1967, the urban rebellions existed because of neglect, racism, and the oppression from an imperfect society. The Harlem rebellion of 1964 and in other places of that same year (like in Rochester, NY, Philadelphia, PA, etc.) made people aware of the seriousness of poverty and economic exploitation. The rebellion in Watts in 1965 caused 34 people to die and $35 million in property damaged. The public feared an expansion of violence to other cities. LBJ at first didn't understand the rebellions because of the civil and voting rights laws that he had passed. LBJ's social programs were less funded because of the Vietnam War.

There was the credibility gap in 1966 as described by the press. What Johnson was saying in press conferences was different than what was happening on the ground in Vietnam. This led the press to show less favorable coverage. By the end of 1966, the Democratic governor of Missouri, Warren E. Hearnes, warned that Johnson would lose the state by 100,000 votes, despite winning by a 500,000 margin in 1964. "Frustration over Vietnam; too much federal spending and... taxation; no great public support for your Great Society programs; and ... public disenchantment with the civil rights programs" had eroded the President's standing, the governor reported. The governor is wrong to disagree with federal spending and fair taxation. Also, civil rights must be promoted as well. People have the right to promote Great Society programs and federal spending despite opposition. On January of 1967, Johnson boasted that wages were the highest in history, unemployment was at a 13-year low, and corporate profits and farm incomes were greater than ever; a 4.5 percent jump in consumer prices was worrisome, as was the rise in interest rates.

Johnson asked for a temporary 6 percent surcharge in income taxes to cover the mounting deficit caused by increased spending. Johnson's approval ratings stayed below 50 percent. By January 1967, the number of his strong supporters had plunged to 16%, from 25 percent four months before. He ran about even with Republican George Romney in trial matchups that spring. Asked to explain why he was unpopular, Johnson responded, "I am a dominating personality, and when I get things done I don't always please all the people." Johnson also blamed the press, saying they showed "complete irresponsibility and lie and misstate facts and have no one to be answerable to." He also blamed "the preachers, liberals and professors" who had turned against him. In the congressional elections of 1966, the Republicans gained three seats in the Senate and 47 in the House, reinvigorating the conservative coalition and making it more difficult for Johnson to pass any additional Great Society legislation. However, in the end Congress passed almost 96 percent of the administration's Great Society programs, which Johnson then signed into law.

Newark burned in 1967, where six days of the rebellion in Newark, New Jersey left 26 dead, 1500 injured, and the inner city burned heavily. In Detroit on 1967, Governor George Romney sent in 7400 national guard troops to quell fire bombings, looting, and attacks on businesses and on police. Johnson finally sent in federal troops with tanks and machine guns. Detroit continued to burn for three more days until finally 43 were dead, 2250 were injured, 4000 were arrested. Property damage ranged into the hundreds of millions. The biggest wave of rebellions came in April 1968 in over a hundred cities after the assassination of Martin Luther King. Johnson called for even more billions to be spent in the cities and another federal civil rights law regarding housing, but this fell on deaf ears. Johnson's popularity plummeted as a massive, reactionary, and racist white political backlash took shape, reinforcing the sense Johnson had lost control of the streets of major cities as well as his party. LBJ passed crime control legislation called the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, which was one ancestor of the Clinton Crime Bill. According to press secretary George Christian, Johnson was unsurprised by the rebellions, saying: "What did you expect? I don't know why we're so surprised. When you put your foot on a man's neck and hold him down for three hundred years, and then you let him up, what's he going to do? He's going to knock your block off."

1967

By January and February of 1967, Johnson continued to reject North Vietnamese calls for peace. Ho Chi Minh declared that the only solution was a unilateral withdrawal by the U.S. A Gallup poll taken in July 1967 showed that 52 percent of the country disapproving of the President's handling of the war and only 34 percent believed that progress had been made. Johnson was angry since he rejected progressive solutions to end the Vietnam War. LBJ made a statement to Robert F. Kennedy about the war. RFK would be a public critic of the Vietnam War and loomed as a challenger of the 1968 Presidential election. Johnson had just received several reports predicting military progress by the summer, and warned Robert Kennedy, "I'll destroy you and every one of your dove friends in six months", he shouted. "You'll be dead politically in six months." McNamara offered Johnson a way out of Vietnam in May. McNamara wanted the administration could declare its objective in the war—South Vietnam's self-determination—was being achieved and upcoming September elections in South Vietnam would provide the chance for a coalition government. The United States could reasonably expect that country to then assume responsibility for the election outcome. Yet, Johnson was reluctant, in light of some optimistic reports, again of questionable reliability, which matched the negative assessments about the conflict and provided hope of improvement. The CIA was reporting wide food shortages in Hanoi and an unstable power grid, as well as military manpower reductions.

By the middle of 1967, almost 70,000 Americans had been killed or wounded in the war. By July 1967, Johnson sent McNamara, Wheeler, and other officials to meet with Westmoreland and reach agreement on plans for the immediate future. At that time the war was being commonly described by the press and others as a "stalemate." Westmoreland said such a description was pure fiction, and that "we are winning slowly but steadily and the pace can excel if we reinforce our successes." Westmoreland wanted more troops, Johnson agreed with an increase of 50,000 troops. The total troops increased to 525,000. By August of 1967, LBJ with the Joint Chiefs supported decided to expand the air campaign. He only exempted Hanoi, Haiphong, and a buffer zone with China from the target list. In September Ho Chi Minh and North Vietnamese premier Pham Van Dong appeared amenable to French mediation, so Johnson ceased bombing in a 10-mile zone around Hanoi; this was met with dissatisfaction. Johnson in a Texas speech agreed to halt all bombing if Ho Chi Minh would launch productive and meaningful discussions and if North Vietnam would not seek to take advantage of the halt; this was named the "San Antonio" formula. There was no response, but Johnson pursued the possibility of negotiations with such a bombing pause. The Vietnam war was in a stalemate. He convened the "Wise Men" for a new look at the war. These Wise Men included Dean Acheson, Gen. Omar Bradley, George Ball, Mac Bundy, Arthur Dean, Douglas Dillon, Abe Fortas, Averell Harriman, Henry Cabot Lodge, Robert Murphy and Max Taylor. McNamara by this time wanted a cap of 525,000 troops and he wanted the bombing to be halted. He was overruled. Johnson disagreed with McNamara and McNamara soon resigned from the administration. With the exception of George Ball, the "Wise Men' agreed that the administration should continue forward. Johnson believed that Hanoi would await the 1968 U.S. election results before deciding to negotiate.

LBJ supported Israel during the Six Day War. In a 1993 interview for the Johnson Presidential Library oral history archives, Johnson's Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara stated that a carrier battle group, the U.S. 6th Fleet, sent on a training exercise toward Gibraltar was re-positioned back towards the eastern Mediterranean to be able to assist Israel during the Six-Day War of June 1967. Given the rapid Israeli advances following their strike on Egypt, the administration "thought the situation was so tense in Israel that perhaps the Syrians, fearing Israel would attack them, or the Soviets supporting the Syrians might wish to redress the balance of power and might attack Israel". The Soviets learned of this course correction and regarded it as an offensive move. In a hotline message from Moscow, Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin said, "If you want war you're going to get war."

The Soviet Union supported its Arabic allies. In May 1967, the Soviets started a surge deployment of their naval forces into the East Mediterranean. Early in the crisis they began to shadow the US and British carriers with destroyers and intelligence collecting vessels. The Soviet naval squadron in the Mediterranean was sufficiently strong to act as a major restraint on the U.S. Navy. In a 1983 interview with The Boston Globe, McNamara claimed that "We d__near had war." He said Kosygin was angry that "we had turned around a carrier in the Mediterranean." Israel also destroyed the USS Liberty which LBJ downplayed when many people died from that incident. Also, Johnson allowed the FBI to illegally wiretap Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It was authorized by the Kennedy administration under Attorney General Robert Kennedy. LBJ said that King was a "hypocritical preacher" because of the extramarital affairs. Johnson authorized the tapping of phone conversations of other people like Vietnamese friends of a Nixon associate. Dr. King publicly said that he will not be intimidated by the FBI's evil tactics. Dr. King was a brave man.

On June 23, 1967, Lyndon Baines Johnson came into Los Angeles. He wanted to participate in a Democratic fundraiser. At that location, thousands of anti-war protesters tried to march past the hotel where he was speaking. A coalition of peace protesters led the anti-war march. Also, a small group of Progressive Labor Party and SDS protesters placed themselves at the head of the march. They reached the hotel and staged a sit down. There were efforts made by march monitors to keep the main body of the marchers moving. They were only partially successful. Hundreds of LAPD officers were at the hotel. The march slowed down. The LAPD ordered the crowd to disperse. The Riot Act was read and 51 protesters were arrested. This was one of the first massive anti-war protests in the United States and the first major one in Los Angeles. There was a clash with riot police. This set a pattern for future massive protests. The event was large. The violence caused Johnson to issue no further public speeches in venues outside military bases. There was a more public protests against the war. On October of 1967, LBJ engaged the FBI and the CIA to investigate, monitor, and undermine anti-war activists. He supported the CIA's Operation Chaos to domestically monitor anti-war people, which is illegal. The CIA is forbidden from monitoring American citizens in American soil for the purpose of surveillance. In mid-October 1967 there was a demonstration of 100,000 at the Pentagon; Johnson and Rusk were convinced that foreign communist sources were behind the demonstration, which was refuted by CIA findings.

1968

Casualties increased in Vietnam in 1968. Success for America was far away and Johnson's popularity radically declined. College students and others protested, burn draft cards, and some chanted, "Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?" Johnson traveled and saw protests. He was not allowed by the Secret Service to attend the 1968 Democratic National Convention. That was when thousands of hippies, yippies, Black Panthers, and other opponents of Johnson's policies converged to protest. These opponents of the war in Vietnam and the opponents of the policies of the ghettoes were very overt in their views. Thus by 1968, the public was polarized, with the "hawks" rejecting Johnson's refusal to continue the war indefinitely, and the "doves" rejecting his current war policies. Support for Johnson's middle position continued to shrink until he finally rejected containment and sought a peace settlement. By late summer, he realized that Nixon was closer to his position than Humphrey. He continued to support Humphrey publicly in the election, and personally despised Nixon. One of Johnson's well known quotes was "the Democratic party at its worst, is still better than the Republican party at its best."

Today is the 50th year anniversary of the Tet Offensive. This was when Vietnamese forces attacked the U.S. Embassy in Saigon and other major cities throughout Vietnam starting in January 30, 1968. Many people died. American forces were taken by surprise. Back then, many American people thought the the U.S. had a near victory in the Vietnam War. After the Tet Offensive, more people realized that the war was a stalemate. LBJ knew of this and hid a lot of this information from the public for fear of being labeled as someone losing the war. The Tet Offensive established a new era of the war and ultimately the anti-war movement grew in power. Public opinion turned against the war. The American forces won the Tet Offensive which included the massive bombing of the city of Hue. After Tet, the Vietnam War changed forever and LBJ soon would not run for President again. By this time, Dr. King was in opposition to the war. I was not born during that time, but my parents were alive back then. 1968 was a year of massive change and one of the most revolutionary years in human history. Ironically, Walter Cronkite of CBS news, voted the nation's "most trusted person" in February expressed on the air that the conflict was deadlocked and that additional fighting would change nothing. Johnson reacted, saying "If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost middle America."

Indeed, demoralization about the war was everywhere; 26% then approved of Johnson's handling of Vietnam; 63% disapproved. Johnson agreed to increase the troop level by 22,000, despite a recommendation from the Joint Chiefs for ten times that number. By March 1968 Johnson was secretly desperate for an honorable way out of the war. Clark Clifford, the new Defense Secretary, described the war as "a loser" and proposed to "cut losses and get out." On March 31, 1968, Lyndon Johnson spoke to the nation and gave his speech entitled, "Steps to Limit the War in Vietnam." He then said that he would desire an immediate unilateral halt to the bombing of North Vietnam. He announced his intention to seek out peace talks anywhere at any time. At the close of his speech he also announced, "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President." By March, LBJ restricted future bombing with the result that 90 percent of North Vietnam's population and 75 percent of its territory was off limits to bombing. On April 1968, he opened peace talks and after extensive negotiations over the site, Paris was agreed to and talks began in May.

When the talks failed to yield any results the decision was made to resort to private discussions in Paris. Two months later it was apparent that private discussions proved to be no more productive. Despite recommendations in August from Harriman, Vance, Clifford and Bundy to halt bombing as an incentive for Hanoi to seriously engage in substantive peace talks, Johnson refused. In October 1968 was when the parties came close to an agreement on a bombing halt, Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon intervened with the South Vietnamese, and made promises of better terms, so as to delay a settlement on the issue until after the election. LBJ accused Nixon of treason for during this. After the election, Johnson's primary focus on Vietnam was to get Saigon to join the Paris peace talks. Ironically, only after Nixon added his urging did they do so. Even then they argued about procedural matters until after Nixon took office.

The 1968 Presidential Election

The 1968 election was one of the most controversial and contentious elections in America. America was the most divided as it has ever been since the American Civil War. Issues of race, class, the Vietnam War, space, hippies, women's rights, housing, the economy, the environment, law and order (which is code for suppressing the rights of the dissenters and promoting the prison industrial complex), and other important issues were part of this election year. By 1968, there was the rise of the hippie counterculture, New Left activism, and Black Power movements. Social and cultural clashes exist among classes, generations, and races. Lyndon Johnson could run for re-election since he served less than 24 months of President Kennedy's term (as found in the 22nd Amendment). Early on, no prominent Democratic candidates wanted to challenge him since he was a sitting U.S. President. This changed by Senator Eugene McCarthy challenged Lyndon Baines Johnson in 1967. McCarthy ran as an anti-war candidate and he was from Minnesota. He was the candidate in the New Hampshire primary. He or McCarthy wanted to pressure the Democrats to oppose the Vietnam War.

By late 1967, over 500,000 American soldiers were fighting in Vietnam. Draftees made up 42 percent of the military in Vietnam, but suffered 58% of the casualties as nearly 1000 Americans a month were killed and many more were injured. By March 12, 1968, McCarthy won 42 percent of the New Hampshire primary vote to Johnson's 49 percent. That was huge for a challenger. LBJ was concerned. Later on March 16, 1968, Robert F. Kennedy of New York entered the race. Internal polling by Johnson's campaign in Wisconsin, the next state to hold a primary election, showed the President trailing badly. Johnson did not leave the White House to campaign. During March 1968, Johnson couldn't control the Democratic Party. It was divided. There were Johnson and Humphrey, labor union, local party bosses, students and intellectuals (who were against the war), Catholics, Latinx, and African Americans (who favored Robert Kennedy heavily). There were also segregationist white southerners who supported George C. Wallace and the American Independent Party. Vietnam divided the party. Johnson couldn't find a way to unite the party since he was stubborn to resist a change in policy. LBJ also had failing health. He was fearful of not living through another 4 year term.

In 1967, he secretly commissioned an actuarial study that predicted he would die at 64. Therefore, at the end of a speech on March 31, 1968, he shocked the nation when he announced he would not run for re-election by concluding with the line: "I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President." The next day, his approval ratings increased from 36% to 49%. Johnson refusing to run shocked the political world. Some speculated on why Johnson decided to not run for President anymore.

Shesol says Johnson wanted out of the White House but also wanted vindication; when the indicators turned negative he decided to leave. Gould says that Johnson had neglected the party, was hurting it by his Vietnam policies, and underestimated McCarthy's strength until the very last minute, when it was too late for Johnson to recover. Woods said Johnson realized he needed to leave in order for the nation to heal. Dallek says that Johnson had no further domestic goals, and realized that his personality had eroded his popularity. His health was not good, and he was preoccupied with the Kennedy campaign; his wife was pressing for his retirement and his base of support continued to shrink. Ultimately, the crisis of the Vietnam War and the Democratic Party in crisis influenced his decision to drop out of the race. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968. It was a very sad time in America. Cities burned in rebellion and people wondered about the future in terms of civil rights and justice. After Robert Kennedy's assassination, LBJ rallied the party bosses and unions to supported Hubert Humprhey at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The problems with the convention was huge. In Chicago (where it was location), the police brutally assaulted protesters and even innocent bypassers. Humphrey was great on civil rights, but very much pro-Johnson on foreign policy.

Some people wanted Johnson to support Nelson Rockefeller. Nixon won the Republican nomination and he used the racist Southern Strategy as a means to play on peoples' fears in the South in order for him to gain conservative Southern white voters (who traditionally voted Democratic). In what was termed the October surprise, Johnson announced to the nation on October 31, 1968, that he had ordered a complete cessation of "all air, naval and artillery bombardment of North Vietnam", effective November 1, should the Hanoi Government be willing to negotiate and citing progress with the Paris peace talks. In the end, Democrats did not fully unite behind Humphrey, enabling Republican candidate Richard Nixon to win the election. The election was very close among Humphrey (whose running mate was Edmund Muskie of Maine) and Nixon (whose running mate was Spiro Agnew of Maryland). Republicans would go on to win multiple future Presidential elections. Humphrey almost won, but he lost.

Later Life

Lyndon Baines Johnson's last day of office was on January 20, 1969. He saw Richard Nixon sworn into office. He decided to smoke despite his daughter's protests, because he felt that he lived his life and it was his turn now to express himself. Later, he came to his ranch in Stonewall, Texas. He literally smoke himself to death. He worked with his former aide and speechwriter Harry J. Middleton to draft his first book called, "The Choices We face." They worked together on his memoirs entitled, "The Vantage Point: Perspectives of the Presidency 1963-1969." It was published in 1971. In 1971, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum opened on the campus of The University of Texas at Austin. He donated his Texas ranch in his will to the public to form the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park, with the provision that the ranch "remain a working ranch and not become a sterile relic of the past." Johnson praised Nixon in foreign policy. Yet, he was worried that Nixon was being pressured into removing U.S. forces too soon from South Vietnam before the South Vietnamese were really able to defend themslves. He said that, "If the South falls to the Communists, we can have a serious backlash here at home." LBJ believed in anti-Communist rhetoric to the very end.

During the 1972 Presidential election, LBJ endorsed Democratic presidential nominee George S. McGovern, a senator from South Dakota, although McGovern had long opposed Johnson's foreign and defense policies. The McGovern nomination and presidential platform dismayed him or Johnson. Nixon could be defeated "if only the Democrats don't go too far left," he had insisted. Johnson had felt Edmund Muskie would be more likely to defeat Nixon; however, he declined an invitation to try to stop McGovern receiving the nomination as he felt his unpopularity within the Democratic party was such that anything he said was more likely to help McGovern. Johnson's protégé John Connally had served as President Nixon's Secretary of the Treasury and then stepped down to head "Democrats for Nixon", a group funded by Republicans. It was the first time that Connally and Johnson were on opposite sides of a general election campaign.

By March of 1970, LBJ experienced an attack of angina. He was taken to Brooke Army General Hospital on Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. He was urged to lose a lot of weight. He had grown to about 235 pounds. He also started smoking after nearly 15 years without having done so. This continued to advance more of his health problems. During next summer, he had chest pains. He started to promote a crash water diet. He shed 15 pounds in less than a month. On April 1972, Johnson fell victim to a second heart attack while visiting his daughter, Lynda, in Charlottesville, Virginia. "I'm hurting real bad," he confided to friends. The chest pains hit him nearly every afternoon—a series of sharp, jolting pains that left him scared and breathless. A portable oxygen tank stood next to his bed, and he periodically interrupted what he was doing to lie down and don the mask to gulp air. He continued to smoke heavily, and, although placed on a low-calorie, low-cholesterol diet, kept to it only in fits and starts.

Meanwhile, he began experiencing severe abdominal pains. Doctors diagnosed this problem through X-rays as diverticulosis—pouches of tissue forming on the intestine. His condition rapidly worsened and surgery was recommended, so Johnson flew to Houston to consult with heart specialist Dr. Michael DeBakey. DeBakey discovered that even though two of the former President's coronary arteries were critically damaged, the overall condition of his heart was so poor that even attempting a bypass surgery would likely result in fatal complications.

His heart condition was now diagnosed as terminal. So, he returned home to his ranch outside of San Antonio. At 3:39 pm. Central Time on January 22, 1973, Johnson suffered a massive heart attack. After he had placed a call to the Secret Service agents on the ranch, they rushed to the former President's bedroom. They found Johnson still holding the telephone receiver in his hand. He was unconscious and wasn't breathing. Johnson was airlifted in one of his own airplanes to San Antonio. He was taken to Booke Army General hospital. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the facility by cardiologist and Army colonel Dr. Georga McGranahan. He was 64 years old.

Shortly after the death of Johnson, his press secretary Tom Johnson (no relation) telephoned Walter Cronkite at CBS. Cronkite was live on the air with the CBS Evening News at the time. There was a report on Vietnam and it was cut abruptly while Cronkite was still on the line, so he could break the news. Johnson's death came two days after Richard Nixon's second inauguration. This was after Nixon's landslide victory in the 1972 election. His death meant that for the first time since 1933, when Calvin Coolidge died during Herbert Hoover's final months in office, that there were no former Presidents still living; Johnson had been the only living ex-President since December 26, 1972, following the death of Harry S. Truman.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was honored with a state funeral. Texas Congressman J. J. Pickle and former Secretary of State Dean Rusk eulogized him at the Capitol. The final funeral services took place at the National City Christian Church in Washington, D.C. as this was the placed where he often worshiped as President. The service was presided over by President Richard Nixon and attended by foreign dignitaries. These foreign dignitaries were led by former Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Satō, who served as Japanese prime minister during Johnson's presidency. Eulogies were given by the Rev. Dr. George Davis, the church's pastor, and W. Marvin Watson, former postmaster general. Nixon did not speak, though he attended, as is customary for presidents during state funerals, but the eulogists turned to him and lauded him for his tributes, as Rusk did the day before, as Nixon mentioned Johnson's death in a speech he gave the day after Johnson died, announcing the peace agreement to end the Vietnam War.

Lyndon Baines Johnson was buried in his family cemetery (which, although it is part of the Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park in Stonewall, Texas, is still privately owned by the Johnson family). The Johnson family doesn't want the public to enter the cemetery. It is also located a few yards from the house in which he was born. Eulogies were given by former Texas governor John Connally and the Rev. Billy Graham, the minister who officiated at the burial rites. Billy Graham recently passed away during this year of 2018. The state funeral, the last for a president until Ronald Reagan's in 2004, was part of an unexpectedly busy week in Washington, as the Military District of Washington (MDW) dealt with its second major task in less than a week, beginning with Nixon's second inauguration. The inauguration affected the state funeral in various ways, because Johnson died only two days after the inauguration. The MDW and the Armed Forces Inaugural Committee canceled the remainder of the ceremonies surrounding the inauguration, to allow for a full state funeral, and many of the military men who participated in the inauguration took part in the funeral. It also meant Johnson's casket traveled the entire length of the Capitol, entering through the Senate wing when taken into the rotunda to lie in state and exiting through the House wing steps due to inauguration construction on the East Front steps. So, we know the truth about his life. We are inspired to carry onward with the social justice credo. Now, it is time to recall his legacy.

Legacy

Looking at the life of Lyndon Baines Johnson is witnessing a life filled with triumphs and controversies. He fought his way into the Presidency. He wasn't born rich. He was born in a Texas community and taught the poor and Mexican children about many educational subjects. He traveled the world and participated in the great war of World War II. Later, he allied with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and was in the Senate of the United States Congress. He was even the Senate Majority leader, which is one of the most powerful positions in Congress. He ran for President in 1960 and lost to John F. Kennedy. He was his Vice President until his assassination on November 22, 1963. Later, he was the President. His helped to pass some of the most progressive legislation in human history like the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, Medicare, Medicaid, and other laws dealing with the environment, the urban community, the rural community, etc. His War on Poverty programs cut poverty in half from 1960 to 1970. His major weakness was foreign policy. The reason was that he acted too militarily aggressive in the Vietnam War (which resulted in destruction, war crimes, and other evils).

He acted so reckless, that the war evolved into a total stalemate and he refused to promote a real negotiated settlement during his Presidency. He believed in the myth that Communists collectively were seeking to take over the Earth and form a global, brutal empire. He also was more reactionary than JFK on foreign policy matters in general by supporting many far right rulers from Greece to the Dominican Republic. His popularity was low massively by 1967 and 1968. He refused to run for re-election in 1968 and saw a Nixon victory. He died in Texas as a man who done so much and achieved many mistakes along the way. His legacy is diverse and it signified the imperfections plus limitations of capitalism and the greatness of the social justice credo. LBJ changed the world and his life is definitely filled with multifaceted complexities. LBJ would also eloquently and legitimate defend immigrant rights too. He could be vulgar and ruthless and he could use commonsense to logically advance civil plus voting rights. Therefore, President Lyndon Baines Johnson was a man whose influence stretches long after the 1960's. That is why in our time, we will continue to advocate for racial justice, economic justice, health care rights, housing rights, investments in infrastructure, environmental protections, an end to poverty, and human liberty.

By Timothy

No comments:

Post a Comment